In early March, after a stunning turn of fortune, the presidential race seemed to crystallize. Either President Donald Trump, whose approval ratings have always been low, would triumph due to the advantage of incumbency, a strong economy and an energized and devoted base of followers, or former vice president Joe Biden, who dominated Super Tuesday, would win as a kind of safe option for weary voters. Three months later, the election seems likely to be about the coronavirus pandemic and anti-racist uprisings - two huge events that were not on the political radar at the beginning of the year.

But this isn't as unusual as it seems.

We have long experienced how unforeseen circumstances and unexpected occurrences - contingency - can alter the course of history just as much as larger structural forces and human decision-making. Although after the fact we often revise our understandings to assign cause and effect, Americans have regularly lived through contingent events. Consider, for example, the 2016 election, when Trump benefited from lucky timing.

His infamous "Access Hollywood" tape came out about a month before the election, causing a dramatic drop in the polls. Three weeks later, FBI Director James Comey's letter to Congress revived coverage of the Hillary Clinton email "scandal," causing her approval to drop and paving the way for a narrow Trump election. What if these dates were switched, and it was Trump's tape that emerged a few days before the election? Or what if Comey did not send his letter? Quite possibly, we would have a different president.

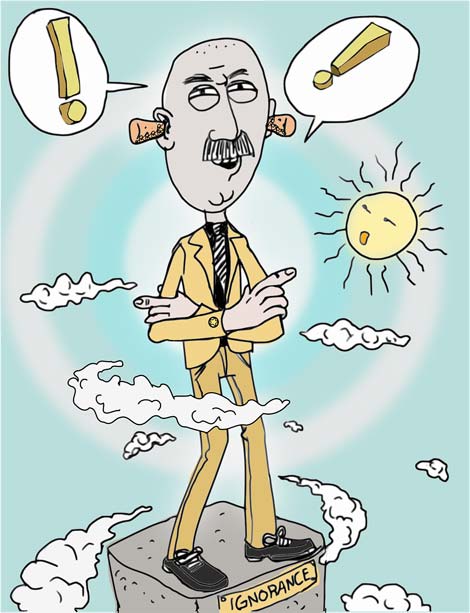

Historians do not often write about contingency because it is impossible to explain. Random, unexpected things just happen. Looking back, after the fact, contingency is easy to forget, and history suddenly becomes baked in. It becomes destiny. Indeed, in the mid-1840s, it became "manifest destiny."

Few symbols are as etched into Americans' brains as the outline of the Lower 48 states. This shape has become a patriotic symbol, alongside the American flag and bald eagle. It seems as if the United States has always looked like this - but, of course, it has not. Almost the entire western half of the country was added in the second half of the 1840s, when the United States annexed Texas, defeated Mexico and took all its northernmost territory and signed a treaty with Great Britain that gave the United States the southern half of what was then called the Oregon Country. Today, we can scarcely imagine a United States without Texas and California, and without the Pacific Northwest and the Mountain West.

But as late as 1844, tens of thousands of Americans could - and did. The trajectory of American politics since the late 1830s made a permanently truncated United States not just possible, but much more likely than the eventual outcome.

Americans suffered through the devastating Panic of 1837, the most severe depression up until that point in U.S. history. Meanwhile, across the southern border in Mexico-controlled Texas, recent migrants from the U.S. had defeated the Mexican Army and declared an independent republic. When they sought annexation to the United States that same year, President Martin Van Buren was too busy dealing with the depression - and, in its midst, too wary of war with Mexico - to agree.

Then, in 1840, William Henry Harrison, the Whig Party's first victorious candidate, defeated Van Buren. One key component to the party's ideology was an emphasis on not expanding the U.S. Improvement at home must come before expansion abroad.

When Harrison died a month into office, John Tyler, more of an expansionist than Harrison, became president. He quickly alienated the Whigs and therefore lacked the political support to launch aggressive foreign diplomacy. Expansion remained on the back burner.

No wonder, then, that throughout the West, Americans who had moved beyond U.S. borders predicted they would forever live beyond these borders - which suited many just fine. After all, since 1837, the U.S. did not seem to be a country on the rise.

During these years, the Republic of Texas tried to expand to the Pacific. In Mexico-controlled California, U.S. migrants fought in the Mexican Army after being promised land titles. In Oregon Country, American migrants contemplated an independent Pacific Republic. In U.S. Indian Territory, Cherokee and Choctaw leaders began to make plans to form a permanent Indian alliance and create an autonomous native republic. In Illinois, Mormon leaders looked west to create an independent empire, which they believed would remain permanently apart from the United States.

Of course, none of this transpired. Why not? The answer lay in a series of unlikely contingencies. We can begin with an infamous wardrobe mistake. On a cold, wet day in early 1841, the newly elected President Harrison gave a two-hour speech without an overcoat or a top hat and soon became ill. Within a month, he was dead, in what is still the shortest presidential term in U.S. history. We now know that it was the microbes of some disease (The flu? Pneumonia?) that killed Harrison, not simply his poor choice of clothing - as was widely reported at the time. Whatever the disease, U.S. history was being shaped by invisible particles, not broad structural change.

If the Whigs had chosen a vice president who shared their convictions, perhaps history would have turned out differently, but instead they chose Tyler, a Virginia slave owner, whose purpose was solely to balance out the ticket and gain southern support. While Tyler and the Whigs disliked the Democratic Party, that was about the only thing they had in common.

So when Tyler became president, instead of supporting the passage of Whig economic policy through a Whig-dominated Congress, Tyler vetoed most of the party's bills. By 1844, Tyler was widely reviled by both parties, and the Whig Party had failed to fulfill any of its political agenda, alienating many voters who had once hoped the Whigs had the answers to ending the economic depression.

In 1844, the Democrats were expected to nominate former president Van Buren against the Whigs' Henry Clay. Van Buren, a New Yorker, needed to mollify southern Democrats who had begun to long for Texas annexation to expand slavery. He botched it, writing a public letter that temporized far too much for southern Democrats' liking.

This hurt his chances of capturing the nomination, and in the end, it went to Tennessean James K. Polk. Although his best political days seemed to be behind him, Polk figured out that supporting the "reoccupation" of Oregon alongside the "reannexation" of Texas would assuage northern Democrats by supporting expansion into both proslavery and anti-slavery lands.

He defeated Clay in the general election thanks to a razor-thin, 5,000-vote victory in New York. Had Clay won New York, he would have won the election - and U.S. expansion would have remained stalled for the foreseeable future. Soon after Polk's election, a prominent Democratic journalist wrote a now-famous article arguing that U.S. expansion - into Texas, Oregon, California and who knew where else - was inevitable. It was "manifest destiny."

Harrison's death. Tyler's presidency. Van Buren's letter. Polk's narrow election. All four were needed for U.S. expansion to happen, and then to be seen as destiny. If all four of these things had not happened, maybe the physical shape of the United States would look different today. And because expansion exacerbated tensions over slavery, maybe the Civil War would have happened very differently.

Whim. Chance. Contingency. Randomness. Call it what you will, but this type of unexpected phenomena drives U.S. political history just as much as the decisions by candidates and their teams, and in turn the decisions of the voters.

Think Biden is on course for a narrow election? He could win in a landslide. So could Trump. Or maybe one - or both - will not be on the ballot in November due to scandal, political implosion or death. Just as we could not know four months ago that a virus would drastically alter our worlds, or that protests would erupt across the globe, neither can we really know what will happen in November. Predict at your own risk.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Richards is the author of "Breakaway Americas: The Unmanifest Future of the Jacksonian United States" and a history teacher at Springside Chestnut Hill Academy in Philadelphia.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author