"There is no more fundamental ethical tension than the tension of the distribution of scarce resources," said Emory University bioethics expert Paul Root Wolpe, president of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors.

In New York, the epicenter of the coronavirus crisis in the United States, the virus's spread has thrown that tension into stark relief. The challenges the state's hospitals face are those that will likely appear in other areas of the country in the coming weeks.

New York has more than 52,000 confirmed cases, the bulk of which are in New York City.

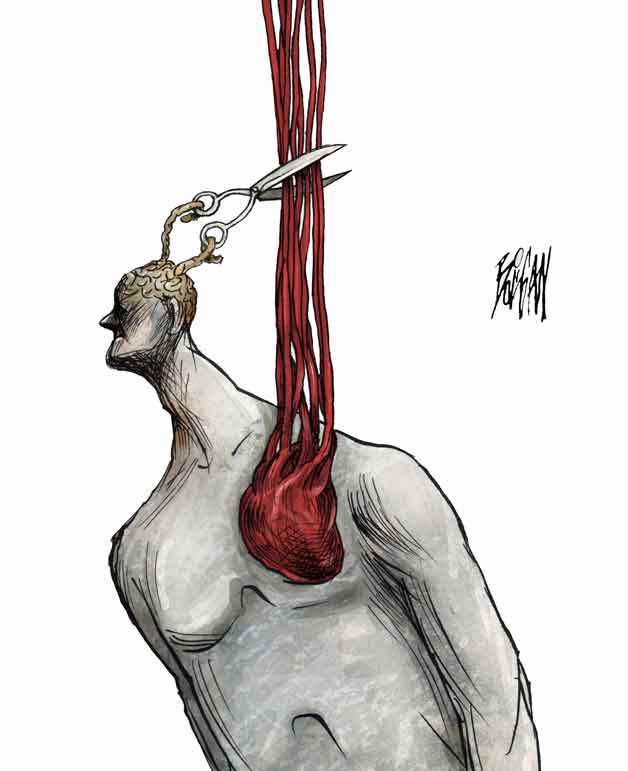

"There's a whole slew of: How do we ration our resources?" said Arthur Caplan, who directs the medical ethics division at New York University Langone Medical Center. "When do we give up on somebody and move on to somebody else?" he said. "How do we balance trying to help people with respiratory failure from the virus versus heart attacks?"

Ventilators, the devices that help pump oxygen into the bodies of critically ill patients, are in short supply. "The ventilators will make the difference between life and death, literally, for these people," Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, told reporters on Tuesday.

New York has about 10,000 of the machines. Officials estimate the state, especially in New York City, will need 30,000 more. "Our supply of ventilators in our public hospitals is really being stressed," New York Mayor Bill de Blasio, a Democrat, told the radio station 1010 WINS on Monday.

This week, some hospitals in the city began sharing single ventilators among two patients via a pathway of tubes. That eleventh-hour technique, also used after the 2017 Las Vegas shooting, risks exposing patients to each others' microbes, said Calvin Sun, a physician who works in New York City emergency departments.

"Hospitals are going to get overloaded. More patients are going to need ventilators," said ophthalmologist Samuel Packer, who was Northwell Health's ethics director during the H1N1 influenza outbreak in 2009.

Packer was a member of an ethics task force that created, in 2015, New York's 300-page guide for the allocation of ventilators during a flu pandemic.

Although it is the foundation for ventilator policies across New York's hospitals, such a massive document is "not really a helpful thing to hand to an intensive care nurse," said Tia Powell, director of the Montefiore Einstein Center for Bioethics. Montefiore's ethicists recently distilled that guide into key points and distributed the abridged version among hospital staff. This includes a plan for phases of increasing severity.

"We're already in phase one," Powell said, in which elective surgeries are canceled and capacity to care for more patients is expanded. In phase two, "you really might be in trouble," she said, requiring the tougher decisions around allocating "scarce resources."

When there aren't enough beds, for instance, "you develop a triage situation," Packer said. That's nothing new for medical experts. (The 200-year-old origin of triage, though it's not quite the same as in a hospital, is attributed to the chief surgeon who tended to Napoleon's Imperial Guard.)

Distributing such resources as ventilators can involve medical considerations, such as whether certain organs have failed.

But they should also involve fairness, social justice and other ethical principles, Packer said. "In ethics, you talk about being utilitarian -- doing the greatest good for the greatest number," he said, which he considers a philosophy well-suited for situations such as these.

Wolpe and his colleagues have been busy reviewing more than 60 pandemic policies from medical centers across the country. "The general idea is very common," he said. "That is to, first of all, prioritize people who are going to make it through."

Although a patient's age is not the only consideration, it is one. "It would be dishonest if we didn't say age is a driver," Caplan said. "Age is correlated with resilience." Because younger patients, in general, get better faster, they may free up a ventilator more quickly for the next patient.

This week, the New England Journal of Medicine published a guide to allocating ventilators. The highest priority, the authors of that report wrote, should be to "save the most lives" and "life-years," not to distribute the machines on a first-come basis. All else being equal, health-care workers and participants in research should receive priority, they said.

But there's no simple formula, Wolpe pointed out. "It's a very difficult, complex and emotionally wrenching . . . process."

The decision to allocate a resource like a ventilator can be a battle within the hospital because physicians so vigorously protect the patients in their care. "Each doctor's patient is more important than the other guy's patient," Packer said. "So ethics gets called. We give them our best shot."

This process can take up to 10 hours, he said -- less in a crisis, when members of ethics committees must "walk and chew gum at the same time," Packer said. When "we have city hospitals that are overwhelmed, in cases like that, we call administration right away," he said, and committees can convene quickly by video chat.

Not everyone will be able to receive "aggressive" treatments but all patients deserve to be cared for, said Renee McLeod-Sordjan, who succeeded Packer as director of medical ethics at Northwell Health, the largest health-care system in the state. "That baseline treatment is comfort. That baseline treatment is relief from suffering."

She struck a note of tenacity. "Hospitals, in general, are prepared quite well for disasters," McLeod-Sordjan said. She has worked through disease outbreaks before, when she was "just becoming a baby nurse" during the 1980s HIV epidemic.

"Being anxious around what's going to happen is an opportunity for mistakes," she said. "One of the things that we're trying to do across health systems and, particularly in medical ethics, is to divorce uncertainty from anxiety."

Part of that, she said, was managing anxious workers and relieving their overloaded schedules. "We're asking people to come out of retirement and to get temporary licenses from the state," so clinicians from other states can assist New York's hospital systems.

"I know that there are people who think, 'This is an emergency! Ethics-shmethics!' " Powell said. "That's a terrible way to think about things in a disaster. You need to remember what makes us human."

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author