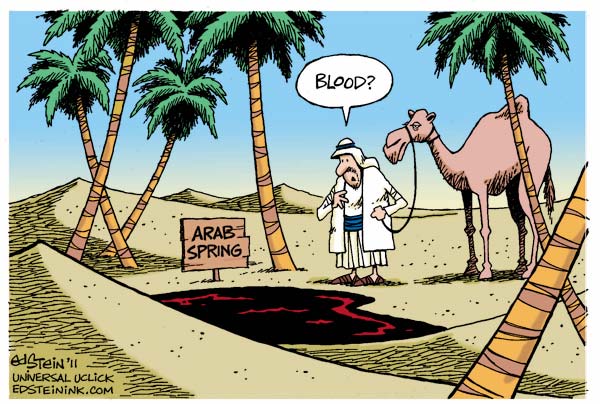

With the exception of Tunisia — the country where the movement began and which made real progress towards a more democratic system, even though there have been setbacks since then — the hopes for a transition from autocracies and dictatorships to a more liberal system have flopped everywhere.

Egypt seemed for a time to be the best example of how a mass movement could overthrow a long-entrenched dictatorial regime with a little help from the United States. Former President Barack Obama helped nudge Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak out of power in 2011 and wound up facilitating the installation of a Muslim Brotherhood Islamist tyranny that was soon overthrown by a military coup backed by most Egyptians. As a result, there is less freedom now than there was 10 years ago. The regime of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi is far more brutal and repressive than Mubarak's ever was.

As for Syria, where a revolt seemed to promise an end to the barbarous dictatorship of the Assad clan, the Arab Spring led to a civil war that not only failed to dislodge Bashar Assad but killed hundreds of thousands of citizens, made millions homeless and left what remained of the country under the thumb of foreign powers like Russia, Iran and Turkey.

Elsewhere, the story is the same. Repressive Arab dictators, oligarchies and monarchies are still in power, and the idea of a push towards democracy or anything like it is regarded as a fantasy.

This defeat exploded the neoconservative vision of the use of American power and influence to promote and expand democracy throughout the world. Despite the polarized nature of American politics with Democrats and Republicans disagreeing on virtually everything, and with each side seeing each other as essentially illegitimate — something that is likely to grow even worse in the wake of the U.S. Capitol riot President Donald Trump incited this week — there is one foreign-policy issue on which there is a bipartisan consensus. Both parties are equally convinced that further military adventures in the Middle East remain out of the question.

While Democrats and some Republicans denounced Trump as an isolationist, most of them now share his view that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as interventions in Libya and Syria, were mistakes. The two parties may still be willing to criticize Middle Eastern tyrannies, though not the same ones, with Republicans focusing on Iran while Democrats snipe at Saudi Arabia. Still, Americans seem united in thinking that any effort aimed at helping the peoples of the Middle East attain freedom is a waste of time, effort, money and blood.

The failure of the invasion of Iraq to transform that country from among the worst tyrannies of the world during the rule of Saddam Hussein to an approximation of democracy had already undermined this thesis long before the Arab Spring led to disaster. Some believed that the triumph of Western ideals of liberty in an Arab world, where they had no historic roots and little appeal, was not only inevitable but a necessary prerequisite for peace. That persuaded many that faith in democracy was practical politics as well as an expression of idealism.

Unfortunately, Iraqi society proved to be intractably tribal. The influence of Iran and Islamist terrorists easily deflated the hopes of some neoconservatives that with enough aid and goodwill, the natural desire of all people to be free and self-governing would create some sort of democratic government.

In retrospect, that idea seems hopelessly arrogant, as well as clueless about the nature of Arab society and politics. Though rooted in a well-meaning belief that others are no less desirous of freedom than those living in the West, democracy promotion ran aground on the harsh reality of the Middle East.

Seen from the perspective of 2021, such efforts to promote democracy have not only failed, but objectively made things far worse for ordinary Arabs than they were before the Iraq war and the Arab Spring. It's clear now that the idea that foreign interventions or a revolt by the Arab street could possibly lead to anything but more chaos, bloodshed, and ultimately, more tyranny was a dangerous fantasy.

In the wake of the Arab Spring, both presidents Obama and Trump were ready to defer to the Russians, as well as Turkey in Syria. And while Trump was bellicose towards Iran, he also demonstrated that his efforts to pressure Tehran would be limited to sanctions and the occasional assassination of a terrorist while avoiding large-scale military efforts. For all his talk of re-engaging with the world, President-elect Joe Biden will likely be even more circumspect about the use of American force.

Regimes like those of Saudi Arabia and Egypt are unpopular in America. But both parties also now understand that their choices in these countries don't include a liberal democratic option. Biden is no more likely than Trump was to prefer an Islamist rather than el-Sisi or the Saudi royal family, for all of their barbarism.

This may lead some in Israel to not unreasonably conclude that they are on their own with respect to dealing with security threats. It's true that a greater readiness to intervene abroad did reinforce the notion that the United States was somehow also ready to rush to Israel's defense, even if the scenarios under which that might happen were always rather remote and apocalyptic.

It's also true that the Arab tyrannies that have emerged intact and/or strengthened from the Arab Spring have proved to be much more cynical, realistic and indifferent to the Palestinian cause. They're also more interested in promoting their own security interests against radicals and Iran, and therefore much closer to openly ally with Israel. In that sense, the failures of Arab democracy movements, which also tended to reflect Arab public opinion with respect to both anti-Semitism and Palestinian arguments against Israel, was also a boost for Israeli diplomacy.

The el-Sisi tyranny in Egypt views its neighbor as an ally against the Muslim Brotherhood. That the Gulf states have embraced Israel and even normalized relations due to their fear of Iran supports that idea. These developments are proving to be of far greater utility to Israel than a theoretical commitment of military intervention from an America that had not been chastened by Iraq and the Arab Spring.

The downside to this for Israel and the United States is what will happen the next time there is a general Arab awakening along the lines of 2011, as inevitably there must be at some point, even if it's in the distant future.

The forces of reaction in the Muslim world are ascendant, and Israelis can hope that the normalization they are embracing will change the hearts and minds of ordinary Arabs about Jews, along with the good it is doing for their governments in terms of military threats and even trade.

But just as the victories of the reactionaries in the Europe of 1848 didn't mean that there wouldn't eventually be another far worse reckoning with revolutionary forces in the next century with the rise of communism, so, too, no one should assume the defeat of the impulse that led to the Arab Spring is permanent. In the meantime, those nations — like the United States and Israel — that are the unlikely beneficiaries of that turnabout will gladly embrace the benefits of the failure of Arab democracy even if they may also lament the defeat of their own ideals there.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Jonathan S. Tobin is editor in chief of Jewish News Syndicate. He's been a JWR contributor since 1998.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author