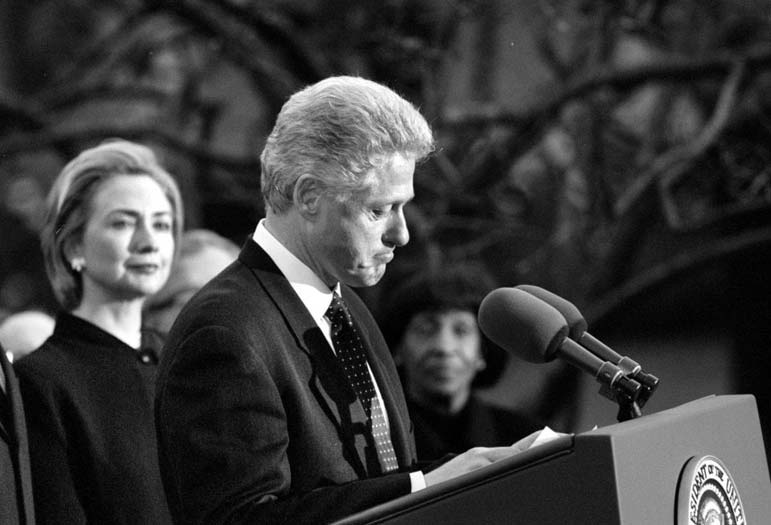

In December 1998, President Bill Clinton thanked Democratic members of the House who voted against impeachment. Washington Post photo by Rick Bowmer

In December 1998, President Bill Clinton thanked Democratic members of the House who voted against impeachment. Washington Post photo by Rick Bowmer

With 19 people charged by special counsel Robert Mueller (including five cooperating witnesses), some believe a case against Trump is imminent. "I'd bet against the president," a lawyer for a target of the Russia probe told Politico. But even some of Trump's critics assert that, unlike governors or foreign leaders, the president of the United States cannot be indicted while in office. Many scholars like Yale professor Akhil Reed Amar insist that "The Framers implicitly immunized a sitting president from ordinary criminal prosecution."

The "implicit" part is the problem. This remains a matter of interpretation and, in my view, a faulty and dangerous one. The case for collusion or obstruction of justice does not yet appear to exist, but if it did, Mueller could indict the president.

The question of whether a sitting president can be charged ultimately turns on which you think is worse: an indicted president or an immunized president who remains in the Oval Office. This debate has long entertained constitutional law professors, alongside other parlor-game questions like presidential emoluments, self-pardons and presidential obstruction. The Trump administration has the dubious distinction of moving all of these questions from the realms of the hypothetical to the actual.

There is one point upon which constitutional scholars uniformly agree: the best course in dealing with a felonious president is to first remove the president from office through the impeachment process and then indict the former president in the wake of the Senate conviction. That is no favor to a president. Impeachment is not subject to the rules of criminal procedure and does not include most of the due-process protections afforded to criminal defendants such as evidentiary protections and prohibitions against hearsay evidence. It can also undermine a criminal defense in a later prosecution by inducing statements from a president that could later be used against him in a criminal trial.

Impeachment is hardly a reliable answer to presidential transgressions. First, the crimes of a president may be popular. (The public overlooked Abraham Lincoln's blatantly unconstitutional unilateral suspension of habeas corpus.) Second, a president's party can control one or both houses of Congress and simply shield the party leader from removal.

There are times when a criminal prosecution may be the only answer for a criminal chief executive. In the case of Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich, D, years of alleged special dealing produced no impeachment. Only after he was charged in office did the Illinois Legislature vote to remove him. But is a president inherently different from a governor? When he was solicitor general of the United States, the late Robert Bork wrote a brief saying that a vice president (like Spiro Agnew) could be indicted in office but not a sitting president. Leon Jaworski, the Watergate special prosecutor, disagreed and suggested that such an indictment might be possible. Recently released material related to the Clinton impeachment shows that the staff of independent counsel Kenneth Starr prepared a memo supporting the indictment of a president and drafted indictments for Bill Clinton.

The Justice Department itself concluded during the Clinton administration that "[n]either the text nor the history of the Constitution" is "dispositive" on this question but has rendered an internal opinion against indictments of a sitting president as a matter of "considerations of constitutional structure." Mueller (who is supposed to follow the department's "rules, regulations, procedures, practices and policies") may consider himself bound to this guidance and put evidence of any crime in a report to Congress for possible impeachment.

But what if he didn't? A Trump indictment would need to overcome two common "inferential" arguments for presidential immunity based on "the uniqueness of the president himself."

• The exclusivity argument The leading argument against indicting a sitting president is that the Constitution does not say you can do it. There is an enumerated process for removing a president, and that is impeachment: "Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal of office," it says. But impeachment is a mechanism for Congress to remove, not punish, a president. The Framers were acutely aware of Parliament's abuses with forms of legislative punishments and fines. They barred such "bills of attainder" and further limited the function of impeachment to removal.

If impeachment is about denying someone the powers of an office, indictment is about holding an individual liable for criminal acts. Impeachment is about the office while indictments are about the individual. Judges, too, can be impeached - even from positions of lifetime tenure -- but nobody holds that they cannot also be charged and convicted while still on the bench. Rep. Alcee Hastings, D-Fla., was a federal judge when he was indicted in 1981. He stood trial in 1983 and was acquitted. It was not until 1988 that Hastings was impeached and later removed from the bench. Likewise, the chief executives of states (with many of the same powers as presidents) have been indicted in office, including the recent indictment of Greitens.

Constitutional provisions often require interpretation, including those affording greater protections like protected groups under the 14th Amendment or barring the death penalty for minors. But those interpretations are based on the extension of an explicit protection while presidential immunity would create a sweeping protection. There is no evidence in either the text nor the Constitution Convention of any intent to create immunity for a president from indictment, even though the Framers spoke and wrote at length on the powers of the presidency.

Advocates for presidential immunity rely heavily on one line by Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist Papers: A president, he said, "would be liable to be impeached, tried, and, upon conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors, removed from office; and would afterwards be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law."

Harvard Law professor Cass Sunstein insists that this quote "means you can't indict and try a sitting president. He has to be removed first." It really does not. In Federalist 69, Hamilton was assuring his contemporaries that they did not have to fear the creation of a "single magistrate." He made this statement to contrast to "[t]he person of the king of Great Britain [who] is sacred and inviolable." He was not expounding on inherent immunity and would hardly be making such an implied argument in an essay designed to quell concerns over presidential powers. Hamilton was assuring readers that a president could be stripped of his office and still prosecuted under the Constitution.

As the Hamilton essay suggests, the Framers were worried about the powers of the chief executive, and such immunity would presumably weigh heavily in that debate, as it should in our current debate. Reading that immunity into the Framers' silence would permit a radical expansion of the powers of the presidency- something most textualists and civil libertarians resist.

• The functionality argument Immunity advocates also argue that, regardless of the lack of textual basis, there is a practical reason the president should have immunity. After all, an indictment would prevent a president from carrying out his duties, particularly if he were sent to jail. In 1976, the Justice Department insisted that any indictment would be an unconstitutional burden since a president is "the symbolic head of the Nation. To wound him by a criminal proceeding is to hamstring the operation of the whole governmental apparatus, both in foreign and domestic affairs."

That overwrought analysis ignores a couple practical considerations. First, it is highly unlikely that a president would be tried, let alone convicted, while in office. Not only do judges defer greatly to the schedule of presidents, but investigations and pre-trial motions can take years. Even when sentenced, appeals can take years. Moreover, if a trial is too demanding, there is the 25th Amendment that allows a president to voluntarily (and temporarily) transfer powers of his office.

The functionality argument also ignores countervailing case law. Bill Clinton spent four years advancing extreme interpretations that allow him not to appear for a civil deposition in the Paula Jones civil lawsuit -- or to seek its dismissal. The Supreme Court ruled against him in Clinton v. Jones in 1997. Yet, despite this rejection of immunity in civil litigation, academics still argue that the president could refuse to do so in a criminal prosecution on the same failed claims. Moreover, it is accepted that a president like Trump can be subject to years of intense investigation by a special counsel and is not immunized from the "distraction" of constant demands for responses, answers, testimony and privilege assertions.

The dysfunctionality caused by presidential immunity should be a greater concern for citizens than the constitutional crisis brought on by an indictment. An indicted president is a terrible proposition. But so is the continuation of a presumed felon in office -- one who clings to power as a shield from accountability. If a president is immune, his supporters in Congress could prevent his removal while the statute of limitations runs out on certain crimes. Conversely, if Congress is shielding the president, an indictment can force him to address his crimes.

Admittedly, the interpretive approach against implied immunity also bars some implied interpretations that can limit presidential powers like presidential self-pardons. Just as the Constitution is silent on prosecuting a president (and thus does not bar such prosecutions), it is also silent on a president granting himself a pardon. Such pardons are presumptively permissible for the same reason that immunity is impermissible. There is no stated limit on the pardon power. Of course, if a president were to issue such a self-pardon, it would likely seal his fate for impeachment. Both the possibility of indictment and self-pardon allow for presidential crimes to be put squarely before the public.

In the end, the Constitution does not protect us from a criminal in the Oval Office. It merely gives us options in dealing with a felonious president.

Jonathan Turley is the Shapiro Professor of Public Interest Law at George Washington University.

Previously:

• 08/17/16 Trump's 'extreme vetting' is harsh, but it would be legal

Comment by clicking here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author