Inspired Living

Uri Zohar's Gift

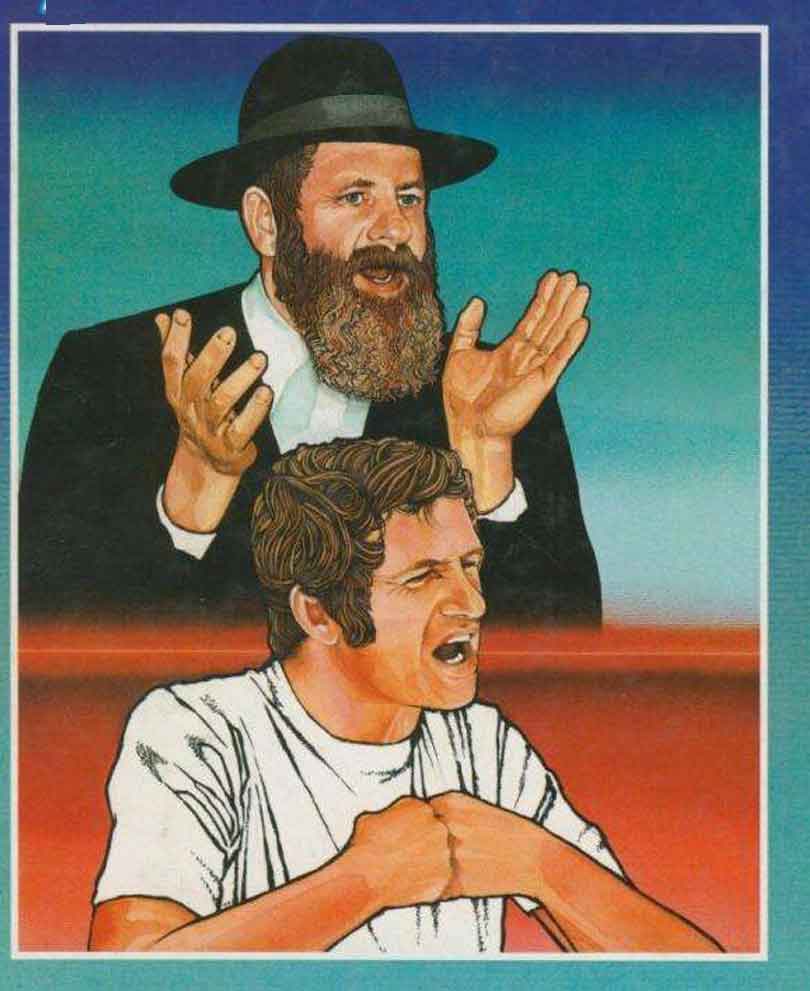

When he first appeared on the talk show he hosted in 1977 wearing a yarmulke, the audience and all those watching at home did not know whether to treat it as part of a skit or real. Until then, he had personified the Ashkenazi secular elite that dominated the country in its first three decades.

His move toward a Torah life made embracing a G od-centered (commandment-driven) life a real possibility for every single Jew in Israel: If the Torah could win over Uri Zohar, how could anyone feel safe?

Amnon Dankner, who would later become editor of the Israeli mass circulation daily, Maariv, wrote at that time of hearing of another old friend entering a Jerusalem yeshiva, Ohr Somayach, every week, and described himself as like an "apple swaying on a tree," not knowing which way he would fall.

Uri Zohar's "conversion" simultaneously infused the still small (by today's standards) Torah community with newfound confidence. Nothing could explain Zohar's sudden shift other than his conviction of the Truth of Torah, for in choosing a Torah life, he put his marriage at risk, and sacrificed the material success and fame he had achieved.

![]()

MY LIFE twice intersected with Rabbi Zohar's. I was privileged to adapt into English (as a junior partner to Rabbi Doniel Baron) his pamphlet on dealing with struggling children: Breakthrough: How to Reach Our Struggling Kids (Feldheim 2016). I reread it after his passing, and remain convinced that it is required reading for every Jewish parent.

His advice on building a loving relationship, based on open lines of communication, with each child long before they reach their teenage years is invaluable. That means creating time to speak … and much more important, listen … to each child every day. Be careful not to respond with pre-packaged Mussar (ethical) lessons, lest our children learn that there are subjects it does not pay to discuss with their parents. And don't live vicariously through your children. "What score did you get on the test?" should not be our most frequently asked question.

Rabbi Zohar wrote about struggling teens from much personal experience with his own children, and of their eventual reconnection to the Divine. The resulting tome is at once filled with common sense and based on deep Torah insights. (He was a serious talmudic scholar, with particular command of the esoteric writings of the rabbinic greats.) The writing is clear, logical, compassionate, and succinct. The book can be read in under three hours.

A child's religious struggles strike parents at their most vulnerable points: their aspirations for their children and their self-image. And consequently, they trigger a host of negative emotions … shame, guilt, fear, and anger … which make it difficult to think clearly, at precisely the moment when thinking clearly is most needed.

Most parents, for instance, recognize that confrontation and denigrating comments are not the likeliest tools to bring their children back. After all, they smile and try to engage their neighbor's religiously deviant child in friendly conversation. But with their own children....

Rabbi Zohar showed parents how to remove themselves from the equation in order to focus on helping their child. Rule one: Don't worry about the opinions of your neighbors. Rule two: Avoid all reactions "cultivated by institutionalized religion, but which do not necessarily reflect true Torah values." If we obsess, for instance, over a child's jeans or hairstyle, we may end up driving away not only the legs wearing those jeans, but the heart and head attached to those legs as well.

Some degree of teenage rebellion is almost inevitable, Rabbi Zohar noted, as a teenager finds himself overcome by powerful emotions and drives with which he or she has had no previous experience. Those drives go with physical maturation, and that physical maturation usually proceeds the emotional maturation necessary for a teenager to regain control.

That means there is often nothing that a parent can do other than exercise patience, waiting for emotional maturation to catch up, while maintaining the lines of communication and showing one's continuing love for one's struggling child. Expressions of love will not be experienced by teenagers as condonation for their actions; they know very well how their parents conduct their lives and their values.

Rather parental love conveys the message that the Torah does not reject him, and that the Divine awaits one's return, just as we pray every year on Yom Kippur that He show patience with us in mending our faults and failures. Exercising patience means that what we don't say or don't do is often more important than what we do or say.

Everyone requires a measure of kavod, respect, and none more so that struggling teenagers. The Talmud (Bava Metzia85a) records how Rebbi brought back the wayward son of Rabi Elazar and the grandson of Rabi Tarfon. In the former case, he began by conferring ordination on the young man, and in the latter's case by offering his daughter in marriage if he returned to a G od-centered life.

Rabbi Zohar's central metaphor for the role of parents in dealing with struggling children is a midrash (Midrash Rabbah Shemos 46:1). The Midrash relates that when Moses saw the dancing around the Golden Calf, he realized he could either retain the Tablets, and the people would cease to exist, for they were no longer capable of receiving the level of holiness contained in the tablets, or he could break them. Even though the Second tablets possessed far less holiness, only they are referred to as "tov, for only they were suitable to the spiritual level of the people. (See Maharal, Tiferes Yisrael 35.)

Similarly, writes Rabbi Zohar, parents must transmit Torah to their children according to their current level. "We need to shatter our own norms, abrogate our 'nonnegotiable' principles.... We cannot be fettered by social convention or any other social convention as we focus on how we can effectively give over Torah to our children."

![]()

MY SECOND OPPORTUNITY to interact with Rabbi Uri came while interviewing him for my biography of Rabbi Noach Weinberg. Even before Rabbi Uri and his wife became fully observant, Rabbi Noach and his wife, Denah, went to visit them at their seaside villa.

Subsequently, Rabbi Noach took on the support of a kollel (scholars' institute), which included a number of highly motivated and talented "born-again" Jews, headed by Rabbi Avraham Mendelsohn, the son-in-law of Rabbi Yitzchak Shlomo Zilberman. Rabbi Zilberman was the primary religious influence on Rabbi Uri's close friend Ari Yitzchak, and subsequently on Rabbi Uri himself.

Rabbi Zohar joined that kollel when he moved to Jerusalem, and studied there for over a decade. His presence was one of the major reasons for Rabbi Noach's ongoing support of the kollel in the Old City. During that period, the two became very close, though they also argued frequently. Rabbi Noach constantly pushed Rabbi Uri to become actively engaged in kiruv (outreach), while the latter considered Rabbi Noach's vision of returning the entire Jewish People to Torah to be detached from reality and felt that he could have a greater impact through the power of his learning.

Not until 1992, after 15 years of nonstop learning, did Rabbi Zohar agree to make five public appearances on behalf of the new Lev L'achim organization, each of which drew large crowds. That reemergence … but now as a full-fledged Torah scholar … was of great satisfaction to Rabbi Noach, and he raised very large sums for Lev L'achim.

My clearest memory of that interview is Rabbi Zohar's lament that the Torah community is filled with many who have no doubt of the Divine's existence, but who view Him as "out to get them." They do not feel that His greatest desire is their good. That lament could have been taken straight from Rabbi Noach, who always made the Lord's constant love the focal point of his teaching.

At some point in the interview, Rabbi Uri must have noticed my amazement at the tiny size of his apartment. He told me laughingly that he was downsizing in preparation for an even more confined space. His body is now there. But his great soul is free to soar unfettered.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

JWR contributor Jonathan Rosenblum is founder of Jewish Media Resources and a widely-read columnist for the internaional glossy, Mishpacha. He is also a respected commentator on Israeli politics, society, culture and the Israeli legal system, who speaks frequently on these topics in the United States, Europe, and Israel. His articles appear regularly in numerous Jewish periodicals in the United States and Israel. Rosenblum is the author of seven biographies of major modern Jewish figures. He is a graduate of the University of Chicago and Yale Law School. He lives in Jerusalem with his wife and eight children.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author