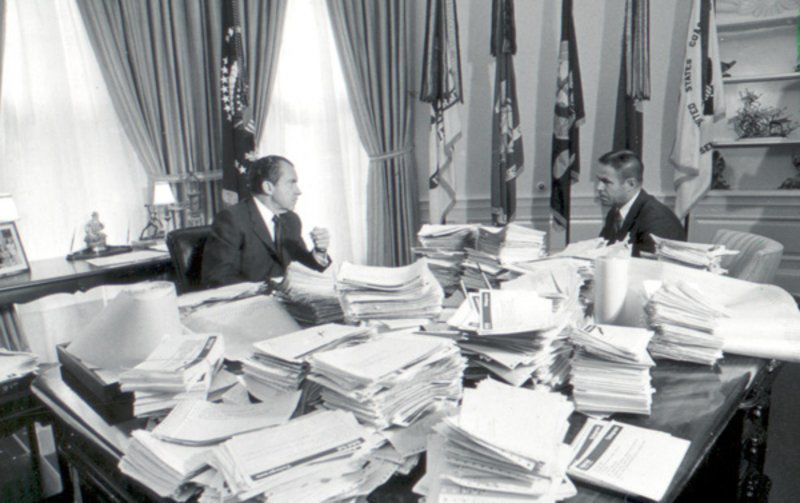

Richard Nixon in the Oval Office with H.R. Haldeman with the telegrams from supporters of his Silent Majority speech.

Richard Nixon in the Oval Office with H.R. Haldeman with the telegrams from supporters of his Silent Majority speech.

Sen. Paul Douglas of Illinois spoke in 1967 of a "silent center."

In the spring of 1969, the prominent campaign chronicler Theodore H. White spoke of America's "mute masses," saying that the challenge for President Richard M. Nixon was to "interpret what the silent think, and govern the country against the grain of what its more important thinkers think."

And so in that context, Nixon's Silent Majority speech, delivered from the Oval Office exactly 50 years ago, is less a fresh departure from American tradition than an address squarely in the American tradition.

Either way, Nixon's Nov. 3, 1969, address was an important marker in American political history, giving powerful voice to a sentiment that long has been part of the main currents of our national life, even as it identified divisions in the public -- and then widened them. It came at a time of grave disquiet about the Vietnam War, and equally grave disquiet about the young men and women who were protesting the conflict by marching in the streets.

But Nixon's audience were those at home, quietly supporting his Vietnam policies, quietly horrified by the disunity in the country, quietly disapproving of the loud public anti-war protest.

"This," said former GOP Rep. Mickey Edwards of Oklahoma, a founding trustee of the Heritage Foundation and onetime chair of the American Conservative Union, "was an important moment, a recognition that there were loads of people not marching in the streets."

So in that moment, with military conflict abroad and political and cultural conflict at home, Nixon decided to deliver a nationally televised address intended to rally support for his dual track in the war -- negotiating with the North Vietnamese while transferring much of the fighting to the South Vietnamese -- while summoning support from an invisible, but potentially formidable, group of Americans at home.

Much of what the president said in his 32-minute remarks is forgotten today, lost in a mist of memories about firefights, Vietnamization and withdrawal schedules -- and in any case is a matter of vague history for the two-thirds of Americans born after the Nixon speech was delivered. But one sentence endures:

And so tonight -- to you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans -- I ask for your support.

Nixon's Silent Majority speech conveyed a message that on the surface beseeched the country for unity but had the effect of dividing the country even further. Both, of course, were part of the Nixon strategy.

"It was a defining moment," the presidential speechwriter Patrick J. Buchanan told me in a recent conversation. "It was a moment when the Beltway media and the Congress were all against him, and yet he stood up and defended his position. It was the strongest moment of his presidency."

It was also a purely distilled Nixon moment. The speech was drafted not by Buchanan nor by Ray Price, who wrote both of Nixon's inaugural addresses and his 1974 resignation speech. Nixon went into near-seclusion to draft this speech; the 60 handwritten pages of his notes and multiple drafts, now in the Nixon library in Yorba Linda, California, make for fascinating insights into the workings of the president's mind. He added the notion of a silent majority only in the margin of one of the pages of his yellow legal pad.

"The president had an instinct this message would resonate, and he felt strongly that in the great 'fly-over country' there was a mass of people -- Nixon people who later became Reagan supporters -- and they just didn't agree with the demonstrators," said Dwight Chapin, a Nixon campaign aide who became a White House assistant responsible for the president's scheduling. "These were two different cultures -- and Nixon knew it. One thing about Nixon: He knew his culture."

The speech won enormous support; the White House switchboard lit up, and Nixon's poll ratings soared. When the broadcast ended, Nixon asked his team how many wires they had received. But Western Union, which was the source of telegrams, was closed for the day. Chapin called the president of the company and persuaded him to open the operation that evening. The result: a pile of expressions of support that filled a table in the Oval Office and produced one of the enduring photographs of the Nixon years.

It also produced divisions that have not healed -- and a presidential technique that has not disappeared.

"It's an old chestnut in American political rhetoric -- invoking a series of values at a moment when those values seem frayed," said Ellen Fitzpatrick, a University of New Hampshire historian.

That may be what prompted President Donald J. Trump to assert, in his inaugural address, that the "forgotten men and women of our country will be forgotten no longer."

Indeed, many of Trump's critics believe there is a direct line between Nixon's Silent Majority speech and the Trump political portfolio.

"This rhetoric was meant to create divisions," said Democratic Sen. Edward J. Markey of Massachusetts. "Nixon's greatest student was Donald Trump, who today is just channeling Richard Nixon. By saying there was greater wisdom in his quiet supporters than in his loud opponents, Nixon played to his own insecurities. But those who were not silent counted as much as those who were silent."

The Silent Majority speech was the opening salvo in a war against American elites, a conflict that endures to this day. Ten days later, Vice President Spiro T. Agnew picked up the call with his own jeremiad against the press and elites, decrying what he called a "little group of men who not only enjoy a right of instant rebuttal to every presidential address but, more importantly, wield a free hand in selecting, presenting and interpreting the great issues in our nation."

Every president since has shared that sentiment, none more so than the current chief executive.

In his presidential memoir, Nixon would write that his speech had "thrown down a gauntlet to Congress, the bureaucracy, the media and the Washington establishment and challenged them to engage in that epic battle."

That battle continues today.

Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

David Shribman, a Pulitzer Prize winner in journalism, is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author