Sen.

Consider

"We danced in a German dance group," he continues. "We wore lederhosen." We then see him doing a little German dance in his lederhosen.

Merker signed up for Ancestry.com and noticed very few Germans in his family tree. So he had his DNA tested through Ancestry.com's test service and discovered: "We're not German at all. Fifty-two percent of my DNA comes from

And then the kicker: "I traded in my lederhosen for a kilt," Merker says. And we see him in his authentic Scottish garb with a big smile.

This is terrible. And Merker is hardly alone. Other ads and services make similar appeals. And they are all based on the idea that your "real" culture and identity exists in your DNA. That is grotesque and profoundly illiberal.

I don't want to pick on Merker. He seems like an entirely decent fellow. Nor do I want to say that investigating your family tree or your DNA is a bad idea. That stuff is fascinating and has all sorts of benefits. But the idea that one could be raised by a family that takes a certain heritage to heart and then cast it aside because of a pie chart on a DNA test is terribly sad to me.

Some people I know are passionate about their Irish heritage and are "black Irish" -- i.e., they have dark eyes and hair and, sometimes, a more Mediterranean complexion. One theory is that they are descendants of Spanish sailors who were stranded on the Irish coast in the 1500s. Another is that they can trace their roots back to one of the countless invasions by Vikings or Normans over the centuries.

I don't begrudge anyone who wants to investigate how their people came to

There's a term for this kind of thinking: "racial purity."

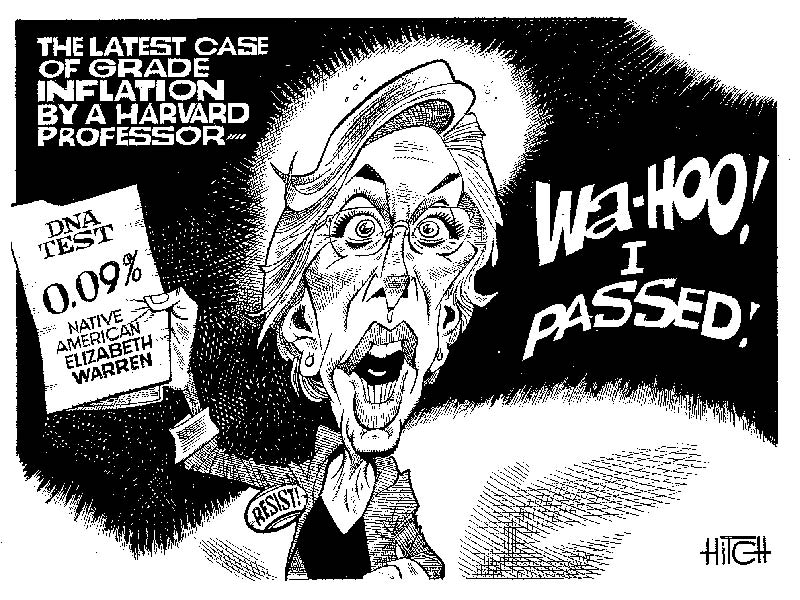

"A DNA test is useless to determine tribal citizenship," the Cherokee nation explained in a statement lambasting Warren.

The idea that you are what your DNA says you are is illiberal, because liberalism (in the classical sense) is premised on the idea the individual is more than just bloodlines. Think of it this way: You know what you call an American citizen with Irish DNA going 300 or 1,000 years? An American. (Or, if you really care, an Irish-American.)

That so many people aren't content with that is a symptom of a much deeper problem with our society today.

(COMMENT, PLEASE, BELOW)

Jonah Goldberg is a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and editor-at-large of National Review Online.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author