Paul Greenberg

over just a child?

http://www.jewishworldreview.com --

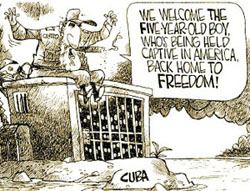

BEFORE IT SENDS the littlest refugee back to Fidel Castro's island prison, the U.S. State Department would like to have American officials interview his father. But according to the usual unreliable sources in Cuba's heavily censored press, his father is demanding the return of 6-year-old Elian Gonzalez to Cuba. He refuses even to talk to American officials unless they can tell him when to expect the boy. At least that's the story out of Havana.

But we all know how a sovietized society works: How can we be sure Dad isn't being coerced into this display of paternal affection for his son, who somehow survived when the boy's mother, stepfather and 10 others drowned in an unsuccessful flight to freedom? Little Elian was found clinging to an inner tube off Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and brought safely to shore, Now his extended family (and a freedom-loving community in Miami) is determined to keep him American. But if the boy's father objects, by all means, he should be granted his unfettered say.

Why not invite Sr. Gonzalez to Miami? There he can hug his son, see how the boy is being cared for and get some idea of the kind of life that awaits the youngster in a free country -- amid a caring family and a warm community that has taken the boy into its heart?

Once in this country, the father could speak freely before an American court. He might even note the difference between American justice, which is based on the rule of law, and what now passes for justice in Cuba.

I remember making conversation with a Cuban lawyer long ago, during that innocent time shortly after Fidel Castro had come to power. Maximum Leader had only started making those marathon speeches over television. I asked what changes, if any, his coming to power had made in Cuban law. My visitor smiled sadly, nodded toward a television set in the corner of room, and said, "That is our law now.''

Getting the elder Gonzalez an American visa to testify in Miami should be no trick. It's getting him out of Cuba that might be tough. Police states are not eager to have their subjects questioned by anyone outside their iron jurisdiction. Who knows what Sr. Gonzalez might say if he could speak freely?

And how you gonna keep 'em in Cuba once they've seen Miami? You never know, Dad himself might apply for political asylum, once he got beyond Fidel's clutches. In the unlikely event Sr. Gonzalez is permitted to visit this country, you can be sure he'll have to leave hostages behind. In all the years I interviewed visitors to this country from the Soviet Union, I never did run across one who was allowed to bring a spouse along.

It may have been Ronald Reagan who noted that whatever the defects of our society, we never had to build a wall to keep our people in. Quite the contrary, we've got to guard our borders to keep people out. That ought to tell us something. And so does how we treat the least of these. Do we open our hearts and home to a youngster whose mother died so he could live free? Do we make an open, honest attempt to talk to the boy's father in surroundings where he, too, can be open and honest and feel free of coercion?

Or do we consult the letter of the law to find some way out that will avoid a diplomatic incident? Why dwell on what effect our decision now will have on a single individual life, and whether this young man will grow up in freedom or tyranny? Aren't those words -- freedom, tyranny -- only words? Let's leave this little business to the diplomats and, as is so often said now about so many troubling moral and ethical questions, move on.

Yes, let's talk about the law and the facts and the diplomatic repercussions of this case, anything but our profoundest convictions.

|

Like so many things that first appear to be a trouble and bother, the case of Elian Gonzalez could prove a blessing. It sheds light, though what it reveals may not comfort. It exposes the curious paralysis of Western values just at a time when they are supposed to be more accepted than ever.

To read the sophisticated legal, diplomatic and political analyses of this incident, all of them delivered in a vacuum of feeling or principle, is to be reminded of how far we have drifted. Maybe something more than freedom for Elian Gonzalez is at stake here; maybe our own attachment to freedom grows tenuous, abstract, removed. Or at least our attachment to freedom for others.

It has come back, the old theory of moral equivalency between Communism and freedom. It was a widespread theory or at least an unstated assumption among our elite during the Cold War -- before everyone claimed to have been in favor of winning it.

And now this case, we're told, is just a simple custody battle between the mother's and the father's side of a family. Why should the United States be involved? What's the difference whether the boy is raised here or there, in Cuba or the United States?

It's enough to bring back all those old debates over arms control, and the common assumption among our enlightened class that the Cold War was just another great-power struggle between two different but morally equivalent systems. They did some bad things, we did some bad things, but, what th' heck, neither side could claim some kind of superiority over the other. Uh huh. Tell it to those who were dying to get out of a Communist society. Who are still dying to get out. Like this boy's mother.

And still there are those, like a late senator from Arkansas, who wonder what possible difference it could make make to some peasant who rules him. (''I stress the irrelevance of ideology to poor, peasant populations.'' -- J. William Fulbright, 1972.)

But still the boat people come, now from Cuba. Still they try to get their children out. For they seem to know something our pundits don't. For example, what life in a Communist dictatorship is like, and why it is better to risk all than stay.

At his presidential press conference last Wednesday, Bill Clinton took a middle course. (Big surprise.) He agreed that, as a father, he would want the boy reunited with his dad, but he added that the interests of the child should be paramount. I'd agree with that.

If little Elian Gonzalez were his child, would Bill Clinton send him back to Cuba, rather than let him stay in the States? Given a choice, would you rather have your child grow up in Fidel Castro's prison isle or in a free country?

It doesn't take a Solomon to decide that question. But the fate of this 6-year-old will not be left

to any Solomon, but to the histrionics of a Latin American caudillo and the equivocations of an

American president who never met an ethical question he couldn't waffle on. Pray for the

littlest refugee. And for all of