It takes strength, patience, endurance, maybe a whole day or even more than one, to clear out a house. To be more specific, a house where someone you know has died. Someone close to you. An aged friend or relative, say, or even a father or mother after a long illness.

Things pile up over the years. The clutter that time leaves behind has built up.

And mixed with it there may be family treasures beyond price: the only portrait of an ancestor extant, or a lone photograph that somehow survived the chaos of a civil war, or the tattered passport that saved an aunt or uncle during the Holocaust....

Fond memories, and some not so fond, are recalled with each discovery. Sometimes you have to sit down and rest, and just think. The whole family may be involved, and need to be.

The more forethoughtful of us, anticipating the inevitable, may mark this item or that for a particular friend or relation. On the bottom of an old lamp or the back of a faded photograph, a note may be found that says: "This goes to Aunt Emily," or "Save this for Cousin Seymour." It takes time to sort out all the things in a house, and there may be all too few such directions.

Questions arise. "Who gets this?" "What's this thingamajig for?" "What in the world are we going to do with the Chinese vase/bedroom suite?" "You take it." "I don't need it. The kids are grown." "Weren't these the twin beds you and your brother grew up with? It'd be a shame to sell them." "How would I get them home?" "Don't worry, we'll ship them ..." "When's the Realtor coming? She'll know what to do...."

There are surprisingly few disputes. Death can have that effect on the living. It tends to put things in perspective, to remind us of what's important. Sibling rivalry disappeared long ago. Who cares now? And so the day passes. Everybody goes out for dinner together, still talking. Or falls silent, still remembering. The house that was once so full now seems so bare. But it's still cluttered with memories. From floor to ceiling, piled high atop one other.

The house in

Quite a few of them, actually, as some incorrigible baseball fans may remember even now. He batted .305 that championship season for the Dodgers, the

They called him Shotgun for the way he could spray line drives all over the outfield -- like so much buckshot.

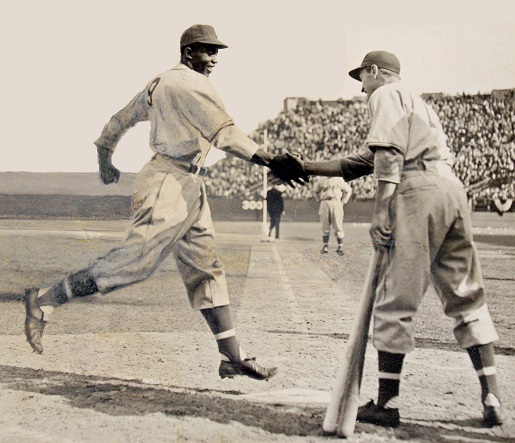

But where were his souvenirs, trophies, clippings? There was just one photograph of any note in the house from his playing days. He kept it proudly displayed in the living room. It had been taken in

Before he went on to challenge other major-league records,

"I couldn't care less if Jackie was Technicolor," he would tell the

Robinson would hit four out of five that day as the Royals drubbed the Giants 14 to 1. In the second game of that season, Shuba himself would hit three home runs.

There were giants in the earth in those days, and not just in physical but moral stature. Robinson would prove a quiet giant in his unassuming self-restraint, fully justifying Branch Rickey's faith in him and his unbelievable self-discipline. He took everything the haters could throw at him without responding, just showing up every day and playing ball. And how. Which was the best response he could have made.

And where did

It takes some of us longer than others to learn that lesson. Some never do. Some learn it only slowly, bit by bit, others in one rush of insight. A schoolboy growing up in the Jim Crow South looked down one day when the trolley car he rode to school came to a sudden stop on the broad avenue, and all of the colored kids in back piled out. (That was the accepted term back then -- Colored or, in more formal contexts, Negro.) They had all headed down a little crossroad -- a muddy, unpaved dirt track, really. And when the trolley lurched forward again, and the boy asked where they'd all gone, he was told there was a colored school down there.

The boy couldn't even see the school from his seat; it was that far away, maybe a mile. But from the condition of the little road he'd seen for just a moment, he could well imagine what it was like -- as neglected as the road all those kids had just taken. His eyes had been opened, and he told himself he would never, never have anything to do with all that business about race. It was wrong, wrong, wrong. And he would never go along with it, let alone defend it.

It's been more than half a century now since that moment of realization, and he's never forgotten it. Or his resolve. Yes, some things stay with you.

Comment by clicking here.

Paul Greenberg is the Pulitzer-winning editorial page editor of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author