The worldwide cataclysm came to be known as the Second World War even though it was really only the second act of the first. It might as well have been called A Tragedy in Two Acts. In 1943, before the war closed with a couple of horrific nuclear explosions over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, an historian at Yale named George Pierson conceived, edited and released a report titled "A Planned Experiment in Liberal Education."

According to Justin Zaremby's fine article in the June 2017 issue of The New Criterion, "A Higher Education: On Seventy Years of Directed Studies at Yale," the fruit of George Pierson's thought and labor turned out to be a grab-bag of complaints about the college education of his time, complete with a plan to remedy them. It was a surprisingly optimistic book considering the tragic times he had just gone through -- a star-spangled, all-American view of a better that awaited ahead.

George Pierson's diagnosis sounds much like one that might be presented today. For he noted the "precarious situation" and "unsatisfactory character" of the typical college of his day -- a widely shared opinion by observers in the academy and outside it among the wider public. The content of courses offered struck George Pierson as superficial and "geared too closely to the average and not very serious students" as they learned more and more about less and less until finally they would have learned nothing at all.

Having fun took up so much of their time, George Pierson concluded, it caused "the development of the young men's mental capacity ... to slip into second place." As he put it, the replacement of required courses with electives had persuaded the students that "all studies were equally broadening and valuable" while the myth of the "uselessness of the liberal arts . . . still persists, both in the public mind" and "in the thinking of many parents and sophomores." Such ideas were, and remain, literally sophomoric. And all too persistent. Except that what he saw as problems are now considered solutions. For why waste time getting a liberal education when the worldly wise just opt for a solely technical one?

"Given the propensity of students to elect easy courses, and of scholars to ride a hobby," George Pierson continued, "is it any wonder that many individual offerings in the B.A. curriculum seem dilettantish, or theatrical, or remote from the realities of life?" How little things have changed since George Pierson set out on his quixotic quest to slay the dragons that still imperil the idea of cultivating a sane mind in a sound body.

But he ended his report on a hopeful note, concluding that his concerns coincided with "that moment in our whole history when we are freest to consider, and to put into practice, really substantial reform. The return of faculty and students with the end of hostilities will mean the golden opportunity of the twentieth century for those colleges which are resolved, and prepared, to take advantage of it." Ah, yes, give 'em a happy ending every time.

But how take advantage of what George Pierson had argued was his and the country's rare moment in time? For the "modern research university faced seemingly irreconcilable tensions among its constituents. Students, faculty and the broader public were all that they knew what mattered in education. Students wanted to pursue their whims and extracurricular fancy. Faculty wanted to pursue their research in departments that were becoming increasingly insular. The public wanted practical knowledge and research that spoke to contemporary war-time needs." Sound familiar?

It all has a familiar ring to those of us following today's debate over the ends and often dubious means of the contemporary university, except that what George Pierson considered a problem is still now being pushed on students as the solution. Those were the days, my friends, when students were expected to be guided by their independent judgment and taste, which someone once defined at the last attainment of an educated mind.

Everything old has become new again, like tried and proved standards for an education and for a life well lived. But how quaint that all seems today, when students are urged to be guided by little but today's ever fluid job market, which would make their decisions about what to study for them.

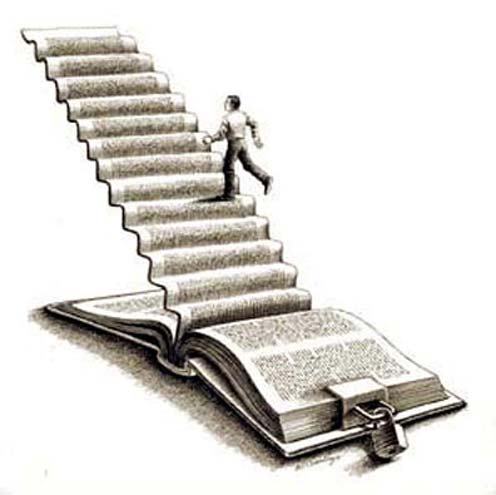

If only we could go back to those halcyon days when education was education, and not just another form of vocational training. And we can if we but will it. But to plan a better course for the future, it's necessary to understand where we've been in the past -- even to have to have lived through it instead of being told about it. Any college history instructor will appreciate what a boon it is to have older, more experienced students in the class who can get up and declare: "Wait a minute, junior. That's not the way it was, not all. And I should know, for I was there."

The map, it turns out, is not the same thing as the road, any more than theory is reality. There are indeed lessons to be learned here, and not all of them come from teachers scarcely dry between the ears.

Comment by clicking here.

Paul Greenberg is the Pulitzer-winning editorial page editor of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author