Whoa. Stop the music. When Ethel Merman belted out "There's no business like show business" as Annie Oakley in "Annie Get Your Gun," a little girl could have been forgiven for believing it. On Broadway in 1946, the stars of showbiz, like the stars across the Milky Way, were protected by myths of glamour and mystery, and the studios could keep the bad stuff out of the newspapers. Naughty deeds went undiscovered and unlamented.

"Annie Get Your Gun" posed other myths for women to live by. Annie took on her rival, a macho cowboy, and she let him know that "Anything you can do, I can do better" and proved it. There was a quickening in the female brain and a flutter in the breasts of women everywhere that a sexual revolution could be powerful and might one day be on the way. It was a seed that flowered decades later.

Life in those bad ol' days wasn't as bad as portrayed in "The Handmaid's Tale" show about abused women in a patriarchal society. The series has just won two Golden Globe awards, but as recently as the first decade of this century, the casting couch was such an accepted showbiz institution that a sign at Disney's California Adventure theme park could advertise a fanciful "Philip A. Couch Casting Agency," an inside joke that provoked only laughter.

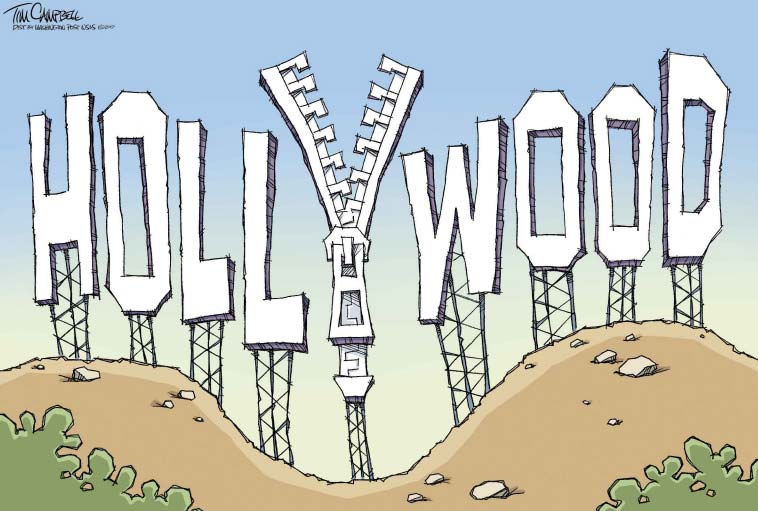

But women in Hollywood have taken off their white gloves and put on black dresses, and they may even have their own candidate for president. But as old myths fall, new ones are challenged. The internet and social media are cruel record-keepers, pushing graphic memory, but not every woman is happy about the preening on the red carpet.

When actress Rose McGowan, who went public with the first rape allegations against Harvey Weinstein, heard of the black dresses planned for the Golden Globes, anger flared. She said in a tweet with the capital letters so beloved by President Donald Trump: "Actresses, like Meryl Streep, who happily worked for The Pig Monster, are wearing black @GoldenGlobes in a silent protest. YOUR SILENCE is THE problem."

No one can accuse women of remaining silent now, but there's occasionally a burst of what sounds like women protesting too much. Streep's brilliance on the screen remains unblemished, but calling Weinstein a "god," joining in a standing ovation for Roman Polanski, who was convicted of raping a 13-year-old girl and fled the country before sentencing, besmirches Miss Streep's moral judgment.

Nor do the numerous photographs of Oprah Winfrey kissing the villainous Weinstein burnish her image in the burgeoning "Oprah for President" movement.

After Elisabeth Moss accepted her Golden Globe for best actress in a drama series for "The Handmaid's Tale," the Twitterscape lit up with accusations of hypocrisy for preaching freedom from sexual harassment as a practicing member of Scientology, a cult accused of covering up abuse. When she said women are no longer "gaps" between stories told by Hollywood — "We are the story" — her remarks were interpreted by some as ironic.

That's doubly true for the unwary in the public eye of the storms surrounding celebrities. Exposing the gap in conversations between the public and the private, critic Daphne Merkin set off a firestorm of political correctness when she wrote in The New York Times that many women are troubled by the "unnuanced sense of outrage" over unproven accusations that border on a witch hunt.

She wrote: "Publicly, they say the right things, expressing approval and joining in the chorus of voices that applaud the takedown of maleficent characters who prey on vulnerable women in the workplace.

"In private it's a different story. 'Grow up, this is real life,' I hear these same feminist friends say. 'What ever happened to flirting?' and 'What about the women who are the predators?'"

The French actress Catherine Deneuve joined a hundred female writers, performers, academics and businesswomen this week to sign a letter in the Paris newspaper Le Monde to denounce what they call "new Puritanism" in the wake of the wave of harassment scandals. With impetuous Gallic ardor, they wrote that men should even be "free to hit on" women.

With an ear well-tuned to both the superficial and the grave, Megyn Kelly of NBC News presented a wide arc of discussion the other day, on two segments of her morning show. In one, women talked of the mixed messages of the expensive black-dress protest, and on the other, she interviewed Brian Banks, former NFL linebacker, about how he was convicted of raping a teenage girl in 2002, spent five years in prison and was released as a registered sex offender. The girl, now a woman, has admitted to making up the story. We're learning that some accusations are more serious than others.

Comment by clicking here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author