Early next month, the world will mark the 100th anniversary of an event that largely shaped the 20th Century and continues to reverberate in the 21st: the Russian Revolution that brought the Communist Party to power on Nov. 7, 1917. Whether this date should be regarded as the beginning of an atrocity or the beginning of a flawed but noble experiment is a question that will come up repeatedly. The answer is not just an academic matter but has continued relevance to the world today.

With its slogans of equality for all, human solidarity, and the elimination of oppression and want, communism appealed to millions of people in the West in the last century. To many, the Soviet Union looked like the realization of a beautiful dream: a state truly run by and for the people, where class divisions were meaningless, workers were liberated from their shackles, women were equal to men, housing and medical care were free and everyone had dignity.

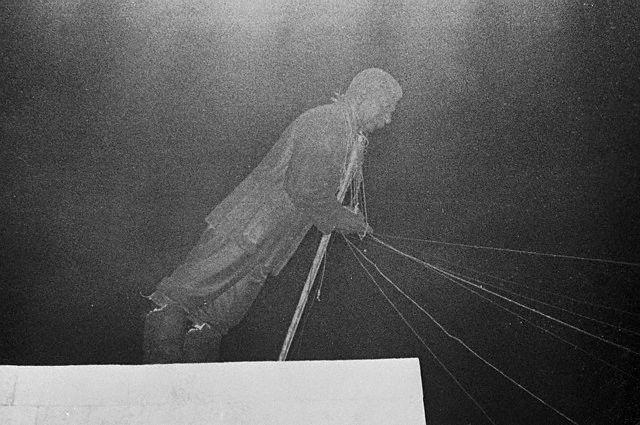

Eventually, this dream clashed with the reality of the gulag - a vast system of camps in the USSR, where not only dissenters but also people accused of minor or nonexistent infractions by a paranoid regime were used as slave labor. Meanwhile, the Soviet regime's promises of social welfare and equality turned into the reality of privilege for the party elite and cramped communal housing, abysmal hospitals and food lines for the rest.

Yet numerous Western intellectuals continued to excuse and romanticize the Soviet regime and communist regimes that followed. Respected journalists such as The New York Times' Walter Duranty and The Nation's Louis Fischer helped cover up the horrific famine that devastated Ukraine in 1932-33, due primarily to Josef Stalin's effort to crush peasant resistance to collective farming.

Later, many claimed that Stalin perverted the communist cause. Yet there is plentiful evidence that terror was part of the Soviet creed from the first days of the revolution. Vladimir Lenin, no less than Stalin, advocated extermination of the "class enemy." His associate Nikolai Bukharin, who was later killed in Stalin's purges and is often touted as a prophet of "humane" socialism, wrote in 1920 that "proletarian coercion," including executions, was "a method of molding Communist humanity out of the human material of the capitalist era."

Communism lost much of its luster in the West after the 1991 fall of the USSR, where I was born before emigrating with my family as a teenager. But now, many people in the post-Cold War generation increasingly disenchanted with capitalism are falling for the romance of communist revolution all over again. It's not uncommon to see the hammer and sickle in the usernames of leftist Twitter accounts. The communist dictatorships of Cuba and even dismal North Korea still have their apologists.

Even in more respectable intellectual circles, communist apologism endures. Just the other day, The New York Times ran a bizarre op-ed by Colorado School of Mines historian Kenneth Osgood asserting that U.S. government-sponsored Radio Free Europe, which broadcast to the Eastern bloc in the 1950s, was the equivalent of the Kremlin's modern "fake news" machine because it promoted the message that "Communism was awful." An earlier Times op-ed extolled the imaginary virtues of women's sexual liberation under communism.

At the end of the last millennium, left-wing journalist Daniel Singer lamented in The Nation that the focus on communism's atrocities not only ignored its positive achievements but served to discredit "collective action and the possibility of radical transformation" in today's world. But collective action and social change are possible within democracy. And the communist experience certainly should be a cautionary tale for those seeking utopia, especially through violence.

Comment by clicking here.

Cathy Young is a regular contributor to Reason magazine and columnist for Newsday.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author