Desperate - and possibly imitating "John Q.," the title character of a 2002 film in which Denzel Washington takes hostages and demands a heart transplant for his son that insurance had refused to cover - Thewes hatched an elaborate extortion scheme to pay for the operation. Alas, he killed someone as part of the crime and ended up under arrest.

Don't worry: None of the above actually occurred. It's a summary of the Dec. 1 episode of "Tatort" ("Crime Scene"), German TV's popular ripped-from-the-headlines counterpart to "Law & Order."

Don't ask why this columnist happened to be watching. (It's a long story.) Ponder instead why television in Germany made such a drama out of imperfections in that country's universal-coverage health insurance - often held up by Americans as a better alternative to the United States' fragmented system.

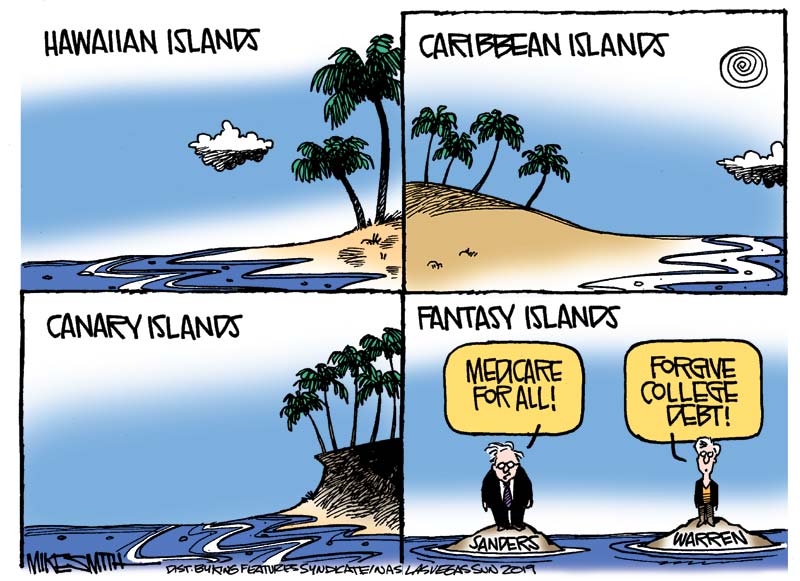

The explanation helps illuminate why Democratic presidential candidates keep getting in trouble over Medicare-for-all.

That promise often includes the assumption, stated or unstated, that the United States must finally guarantee health care to everyone, just like "every other major country on Earth," as Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., so often says.

To be sure, Germany, like most European countries, insures practically all its people, at lower per capita cost, than the United States does.

But what neither Germany nor any other country on Earth, major or minor, does is "guarantee" everyone health care, in the sense of assuring them all the care they want, at a price they can afford, no matter what.

Trade-offs in health care are real, and not merely the result of insurance company or drug company greed - though the pursuit of profit certainly can make matters worse, as the epidemic of addiction to heavily and sometimes unethically marketed prescription opioids has shown.

Even under universal coverage, people may not be covered for treatments deemed too expensive in relation to likely benefits. In fact, such systems could not work, financially, without limitations on access to specialists, devices, experimental drugs and the like.

Cost containment can irk middle-class Germans who pay a mandatory 8.2% of their earnings for health insurance - only to find it lacking in rare extreme cases, or even non-esoteric ones.

The "Tatort" episode built sympathy for the Thewes character by repeatedly mentioning the law-abiding civil servant's dutiful contributions, contrasting them with the illicit means by which the target of his extortion plot - a Turkish-immigrant businessman - accumulated his cash.

It was a bit melodramatic, to be sure, but screenwriter Oke Stielowtold me he researched the real-life struggles of those living with rare "orphan diseases" in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. TV critics in Germany generally liked the show; none challenged its premise.

Why should they? It's consistent with the reality that, over there, everyone can get pretty good care for most conditions while, on this side of the Atlantic, people with super-good insurance get super-good care - even for quite arcane ailments - while some people get relatively poor care, or none at all. (For what it's worth, Stielow mentioned to me that, "I tore my Achilles tendon, and it took four months to find a doctor to really help me.")

Of Medicare-for-all proponents, Sanders is the most honest, in that he admits it can be funded only if the middle class pays, as in Germany.

His bill, however, would provide a benefits package "significantly more generous than the single-payer plans run by America's peer countries," as a recent Vox analysis put it, including unlimited choice of physicians and medical, dental and vision coverage at no up-front cost to consumers. Only a zero out-of-pocket package such as this could beat even the best private insurance plans available now.

Still, many voters regard Sanders's promise as a bit too good to be true and therefore not worth abandoning the devil they know, private employer-paid insurance.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., co-sponsored Sanders's bill, then promised that taxes on the rich would pay for it - and then hedged further by saying, if elected president, she would not pursue Sanders-style abolition of private insurance until her third year in office. Her sagging poll numbers suggest it didn't work. Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., tried an even more complicated circle-squaring exercise, and now she's a former presidential candidate.

When it comes to health care, people want the full range of services, low cost and freedom of choice.

Those three objectives are in tension with one another; Democrats are quite right that the United States could resolve the tension much more fairly and efficiently. As any "Tatort" viewer could tell them, though, no country can eliminate it.

Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author