The debate over the weekend about whether President Donald Trump or his lawyer wrote a tweet saying National Security Adviser Michael Flynn was fired for lying to the FBI is fascinating -- and beside the point. Despite the enthusiasm of administration critics, a tweet can't and shouldn't be the basis of a "confession" of a high crime for impeachment purposes.

In other words, regardless of authorship, the tweet can't be used to prove Trump obstructed justice because he knew about Flynn lying to the FBI when he urged Director James Comey to go easy on Flynn and then fired Comey.

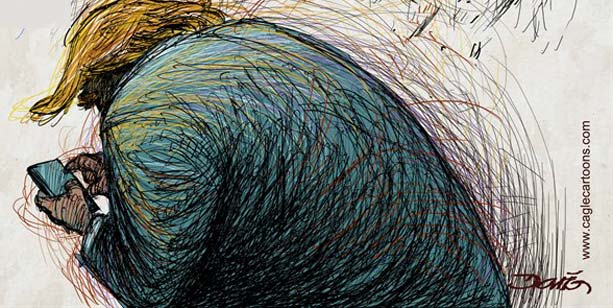

The reason lies in the way the medium carries the message. Twitter doesn't exactly lend itself to accurate descriptions of the inner state of anyone's mind. To the contrary, tweeting is all about public self-presentation -- including overstatement, self-promotion and self-justification. What's more, we know that multiple people tweet for Trump, making it difficult to ascribe the content of any one tweet to him as proof of criminal intent.

Tweets do have a place in court, to be sure. They've already been cited by lawyers and judges to explain Trump's political motivation behind public acts like the Muslim travel ban. But there's a big difference between setting the political context of an official government action and revealing the necessary intent for a crime. One is external and public, exactly what Twitter is all about. The other is internal and private -- the opposite of the Twitter form, even for an apparent stream-of-consciousness user like Trump.

Admittedly, the tweet in question does sound more like it came from Trump, rather than lawyer John Dowd, who told CNN on Sunday that he had "drafted" it. For one thing, a good lawyer generally doesn't advise a client to introduce new elements into an already controversial narrative.

That's exactly what the tweet did: Where Trump had said that he fired Flynn for lying to Vice President Mike Pence about his conversations with Russian Ambassador to the U.S. Sergey Kislyak, the tweet added that Flynn had also been fired for lying to the FBI. Introducing a new element is confusing and potentially contradicts earlier statements, even when it doesn't also create the appearance of obstruction of justice.

But none of this matters for impeachment purposes. Assume, for the sake of argument, that Trump did write the tweet. The fact that, in December, Trump offered a new explanation on Twitter for conduct that took place in February, doesn't prove much of anything about his state of mind nine-and-a-half months before.

Thus, for example, Trump could simply have been trying to deflect attention from Flynn's guilty plea Friday for lying to the FBI by claiming that he knew about the lies all along and relied on them when firing Flynn. That is, Trump may have been embellishing the truth, or even outright lying, when he added Flynn's FBI lies to his story.

Twitter lends itself to this kind of exaggeration. The forum favors sharp, overstated forms of expression. A tweet isn't a formal White House statement (or at least not always).

Above all, Twitter is a publicly oriented forum. What one says there need not reflect one's inner state. Like other social media, the genre rewards the creation of a public persona that may be very much at odds with one's private beliefs and conduct.

What's needed to prove what Trump actually knew and the basis for his motivations when firing Flynn can't be gleaned from this public format. To prove a crime, including a high crime, we need access to the alleged criminal's private thoughts at the time of action. That can come in the form of testimony from confidants, contemporaneous emails or messages, or even inference from conduct. A tweet doesn't qualify.

That said, Twitter can be used as legal evidence of motivation in non-criminal matters. Consider the courts that cited Trump's tweets, alongside other evidence, to show that his travel ban was tainted by anti-Muslim bias. Those courts were making inferences on the basis of the political context in which the travel ban was shaped and promulgated.

For the purpose of understanding the political environment, Trump's tweets are fair game. They reflect precisely the public meaning Trump intended the travel ban to have, which was anti-Muslim.

Crime is different, because the relevant intent isn't a public fact but a private one, a matter of the actor's mind. Twitter may seem like a record of our innermost thoughts, or at least of Trump's. But it isn't, not by a long shot. Twitter doesn't tell you what anyone is thinking, just what they want you to think they're thinking. That's important in politics.

But that isn't enough to reflect criminal intent, whether in court or in a Senate trial for impeachment.

Comment by clicking here.

Noah Feldman, a Bloomberg View columnist, is a professor of constitutional and international law at Harvard University and the author of six books, most recently "Cool War: The Future of Global Competition."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author