Tibor Rubin was a teenager when he was deported in 1944 to Mauthausen, the Nazi concentration camp complex in Austria. A Hungarian-born Jew, he was orphaned in the war and developed a keen survival instinct. He stole food, raided garbage and learned improvised medical techniques, like maggot therapy for gangrene. He called himself, with pride, the "Little Rat."

He was a disease-ridden skeleton when American troops liberated Mauthausen. But for the first time in 14 months, he was free. He vowed, he later said in broken English, "If the Lord have me, if I ever go to America, I gonna become a GI Joe."

He did just that, cheating his way into the Army, he said, by cribbing the entrance exam and landing on the front lines as the Korean War began. His sergeant, by many accounts a sadist and anti-Semite, repeatedly sent him on seemingly certain-death assignments.

In summer 1950, Mr. Rubin was "volunteered" to defend a strategic hill while the rest of his company withdrew to safety near the Pusan Perimeter amid an onslaught by North Korean troops. He armed himself with grenades and guns and waited, knowing the sergeant had no intention of relieving him, ever.

The enemy attack began at dawn, and Mr. Rubin said he became "hysterical" as they swarmed the hill "like ants."

He fired helter-skelter, lobbing grenade after grenade to create the impression of more than one man. "Pull the pin, boom, pull the pin, boom," he said. Unable to see through the resulting smoke, he kept up the defense for a full day, defending his post until American-manned Corsairs repelled the remaining North Koreans from the air.

"He inflicted a staggering number of casualties on the attacking force during his personal 24-hour battle, single-handedly slowing the enemy advance and allowing the 8th Cavalry Regiment to complete its withdrawal successfully," read his citation for the Medal of Honor, the military's highest award for valor.

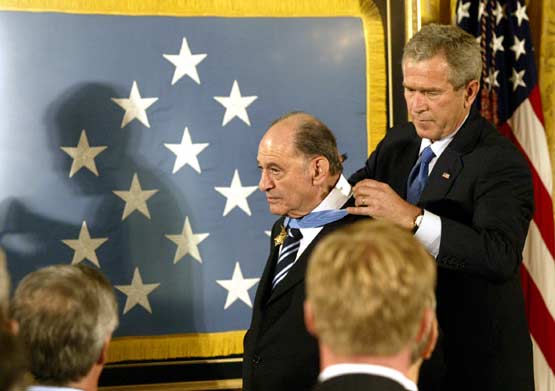

President George W. Bush bestowed the award on Mr. Rubin in a 2005 White House ceremony, part of a congressionally-mandated effort to identify veterans who might have been overlooked for the medal in earlier decades because of racial, ethnic or religious discrimination.

Mr. Rubin, the only Holocaust survivor to receive the Medal of Honor, died Dec. 5 at a hospice center near his home in Garden Grove, California. He was 86. The death, of unspecified causes, was confirmed by Daniel M. Cohen, a filmmaker who wrote a biography of Mr. Rubin, "Single Handed," that was published this year.

Mr. Rubin said that after the battle, he staggered down the hill and saw in the daylight countless maimed and lifeless bodies. He heard agonized screams in Korean from the wounded.

"I had the guilt feeling what I did here," he later told an interviewer with the Holocaust Awareness Museum and Education Center in Philadelphia. "I killed even the enemy but I killed somebody's father, brother, and all that. . . . But then again, the truth is that if I don't kill him, he kill me and vice versa. It's war. War is hell."

The elder Rubin, Ferenc, had been shaped by tragic times. He and a twin brother served in the Austro-Hungarian military in World War I and were captured by the Russians. Both were sent to a labor camp in Siberia, but only Ferenc made it out alive. He walked the entire distance home to discover that his wife, the mother of his four children, had remarried in his years-long absence and presumed death.

Ferenc married twice more and raised two children, Tibor and a daughter. They spent part of their childhood in a home that Ferenc eventually opened to Polish refugees escaping the Nazi threat.

In spring of 1944, it was decided that Tibor would accompany a small group of Poles making their way to neutral Switzerland. They were caught and handed over to the Gestapo. He would never again see his father, stepmother or younger sister, all of whom died in the war.

After Mauthausen was liberated in May 1945, Mr. Rubin spent three years in a displaced persons camp in Pocking, Germany, before reuniting with older half-siblings, who had long before settled in the United States. While working as a shoemaker and butcher, he twice failed the U.S. Army entrance examination because of the language barrier.

Cohen said Mr. Rubin's determination, as well as the Army's need for troops amid hostilities in Korea, won over the recruiter, who advised him to steal glances at the paperwork of other test takers.

After the events for which he received the Medal of Honor, Mr. Rubin continued to be thrown into danger by his sergeant.

Following initial setbacks to the Communist forces, Mr. Rubin's 8th Cavalry Regiment was part of a massive NATO counteroffensive that pushed deep into North Korea. The regiment came under fierce attack in October 1950 by the Chinese, who had crossed the Yalu River en masse and overwhelmed Mr. Rubin's thinly stretched unit near Unsan.

Many in his group were killed over days of fighting, but Mr. Rubin was credited with slowing the advance with a machine gun. By the time he was taken prisoner by the Chinese, he had been wounded by shrapnel in his hand, chest and leg.

His captors repeatedly offered to repatriate him to Hungary, but he declined. Instead he stayed on in the isolated camp that the Americans called "Death Valley." Unlike many young American GIs, Mr. Rubin could draw on the experience of wartime adversity to survive. He sneaked out repeatedly and brought back food stolen from local farms and storehouses.

He did his best to raise morale when other soldiers were paralyzed by fear or freezing weather during the brutal winter of 1950 and 1951.

"Some of them gave up, and some of them prayed to be taken," Mr. Rubin later told Soldiers magazine. He did his best to rally them, reminding them of relatives praying for their safe return home.

Decades later, fellow POW Leo A. Cormier Jr. told interviewers that Mr. Rubin carried sick men to the latrine and spent hours picking lice from the hair of listless soldiers.

"He did many good deeds, which he told us were mitzvahs in the Jewish tradition," Cormier noted. "He was a very religious Jew and helping his fellow men was the most important thing to him."

In April 1953, Mr. Rubin was suddenly returned to the United States in an exchange of sick and wounded prisoners, and he settled with his half-siblings in Southern California.

He wanted to get on with his life. He became a U.S. citizen and then a partner in a family-run liquor store. In 1963, he married Yvonne Meijers, a Holocaust survivor from the Netherlands whom he met at a dance for Jewish singles.

Besides his wife, of Garden Grove, survivors include their two children, Frank Rubin and Rosalyn Rubin, both of Orange County, California.

"Teddy" Rubin, as Tibor became known, largely avoided talking about World War II and Korea. But in the 1980s, he attended a reunion of veterans, where he reconnected with members of his unit. They expressed shock that he had not received the Medal of Honor.

He was told that he had been nominated four times by his grateful comrades - efforts, it emerged, that had been blocked by the sergeant. Mr. Rubin had received two awards of the Purple Heart, but he was the "least assimilated of all his relatives," said Cohen, and probably knew and cared little about medals.

The Jewish War Veterans of the United States began lobbying in the late 1980s for recognition of Mr. Rubin's wartime heroism. In 2001, when Congress ordered the Defense Department to review the war records of Jewish and Latino servicemen who might have been unfairly denied the Medal of Honor, Mr. Rubin headed the list. In his citation, he was credited with saving as many as 40 of his fellow prisoners.

"I waited 55 years," he later said of the ceremony at which he was saluted by generals and other potentates. "I said listen, yesterday I was just a schmuck. Today, they call me, 'Sir.' . . . How I made it, the Lord don't even know. I don't even know because I was so many times supposed to die over there, but I'm still here."

Comment by clicking here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author