More to the point, we take it for granted that certain axioms of human morality are too hard-wired to be forgotten. The seven Noahide laws — which include the basic tenets of the social contract — are so fundamental to human sensibility that the Talmud (Sanhedrin 56 b ) finds an allusion to them all the way back in the Almighty's first commandment to Adam in the Garden of Eden.

Even among the most ardent libertarians, no one argues against the immorality of murder or stealing; and despite the permissiveness of secular culture, the large majority of Americans still condemn adultery as morally wrong.

At the same time, even those who consider themselves religious are quite capable of rationalizing their way around almost any moral impediment. People whose aversion to murder makes them challenge the morality of capital punishment may be equally passionate in their support for euthanasia, partial-birth abortion, and the "selected non-treatment" of handicapped newborns.

Few people seriously contemplate bank robbery, but fudging our taxes or "borrowing" supplies from work raises no pang of conscience. Most of us are committed to our spouses but, according to one poll, half of all Americans have either had an affair or expect to have one.

Even the most righteous among us are not immune from moral indiscretion. As the sages Taught (Baba Basra 165a): Most people are guilty of theft; a few are guilty of sexual immorality; and everyone is guilty of loshon hara (gossiping).

CHARTING COURSE BY OUR MORAL COMPASS

So what makes some of us more moral than others? Is moral conduct simply the absorption of cultural values or submission to some doctrinal code? Are we nothing more than products of our environment, or is there some moral imperative programmed into the human psyche that we can channel through sheer force of will? Why is the path of virtue often so hard to find and why, even in moments of moral clarity, do we experience such dissonance between our minds and our hearts?

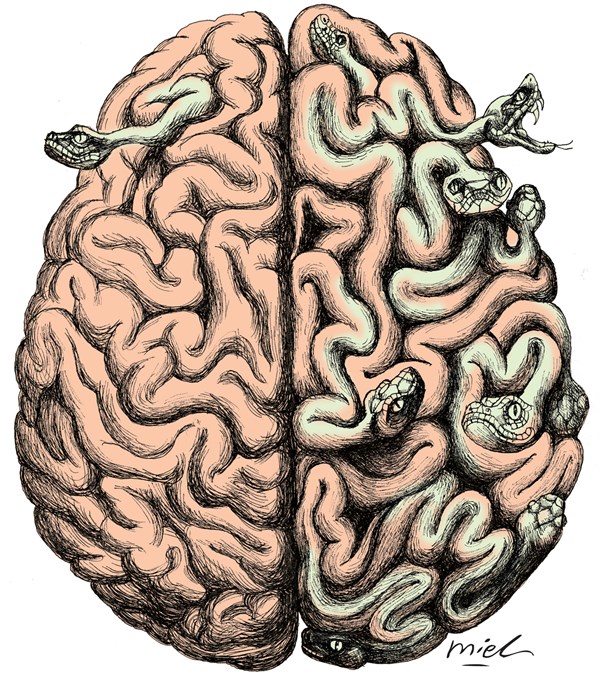

Perhaps the problem is with our terminology. In the language of Torah, the conflict between good and evil is not expressed as a battle between the heart and the mind; rather, it is described as a struggle between the impulses of our emotions, symbolized by the heart, and the reasoning of our conscience, represented through the curious imagery of the kidneys.

Thus did King David describe the Divine as "the One who examines hearts and kidneys," referring to our emotions and our intellect respectively (Psalms 7:10).

As the engine that powers the body by pumping lifeblood to every organ and sinew, the heart serves as a logical symbol for the seat of impulse and emotion. But since it is the brain that controls our thoughts and our reason, why did David choose our kidneys as the symbol of the human mind?

THE BIOLOGY OF VIRTUE

Tipping the scales at only about half a percent of our total body weight, the kidneys receive 20 percent of the blood pumped by the heart — about one liter per minute. This enables them to regulate the composition of our blood by filtering out waste and toxins, maintaining constant levels of water, calcium, and acid, as well as constant blood pressure, and stimulating the production of red blood cells, which carry oxygen throughout the body.

It may well be our dependence upon a steady flow of oxygen to the brain that inspired David to identify the kidneys as essential to the sound functioning of the intellect. Or perhaps it was a deeper connection between the earliest awakening of collective Jewish conscience and the filtering operation of the kidneys that suggested David's allegory.

Although the Torah itself tells us little about the spiritual development of the first Jew, tradition recounts many episodes of how, even as a young boy, our patriarch Abraham rejected the idolatrous notions and practices of his time.

Over four centuries before the Law of the Torah would be revealed to his descendants at Sinai, Abraham discerned the Divine Will on his own by observing the nature of the world around him.

Cryptically, the sages tell us that Abraham was taught the Law by his kidneys before he developed a full recognition of the Almighty.( Bereishis Rabbah 61:1)

This seems to suggest that Abraham was only able to perceive the worldly presence of his Creator after he had filtered out from his consciousness all the toxic elements of the material world. Without the kidneys ceaselessly removing contaminants the human body, our systems would become so polluted that we would quickly fall ill and expire.

In the same way, the mind keeps the human being spiritually healthy only when it filters out the contaminating influences of ego, sensory gratification, and foreign ideas. Just as the pure flow of blood is necessary for a sound mind and body, pure thinking is necessary for a healthy soul.

The Talmud (Brachos 61a) refines this idea further by stating that, "One kidney prompts a man to do good, and the other prompts him to do evil."

Even the capacity of reason can be perverted if our hearts are not committed to what is good and what is true. In the same way that sound reasoning can rein in the impulses of the heart, similarly the longings of the heart give can free rein to the power of rationalization. This may explain why many translators rendered the word caliyos literally "kidneys" — as "reins," relating to the renal system that keeps our blood clean and oxygenated so that our minds remain clear enough to rein in the promptings of physical passion.

And so King David declares, "I will bless G0D, who has counseled me; also by night my kidneys direct me" (Psalms 16:7).

When the moral choices we face are clear to us, the Torah points us confidently along the path of virtue, guided by the Divine "counsel" of our hearts. But often we find ourselves facing the darkness of moral uncertainty and groping through the "night" of spiritual confusion. For those times, the Creator designed us with the ability to filter out the bad from the good, the spiritually toxic from the morally pure.

Like the tiny cells that make up the totality of our bodies, the myriad decisions that govern the countless actions of our lives make up our moral and spiritual identities. Every little victory over anger, arrogance, laziness, and self-indulgence purges a few particles of spiritual impurity from our souls. Every time we conquer procrastination, bite our tongues against malicious gossip and hurtful speech, or humbly allow others to enjoy their moment in the sun, we bring ourselves — and our world — a little closer to the purity of Eden.

If we are sincere in our desire to rein in the impulses for our hearts, if we allow our minds to filter out self-interest from spiritual ideals, then we will discover that the moral challenges of our lives, no matter how difficult, are not cause for confusion.

And once we achieve moral clarity, then we can walk confidently in company with the righteous along the path of eternity.

Comment by clicking here.

JWR contributor Rabbi Yonason Goldson teaches at Block Yeshiva High School in St. Louis. He is the author of books on Judais philosophical themes.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author