There's been much harumphing about how Republicans who didn't get on board are in the tank for President Trump. But it was a singularly misbegotten bill.

Plan A, i.e., passing the thing, would have been hard enough. But supporters apparently didn't think through a need for a Plan B or C: Trump would have vetoed the bill if it passed Congress, and if it somehow passed Congress with a veto-proof majority, the Supreme Court would likely have struck it down.

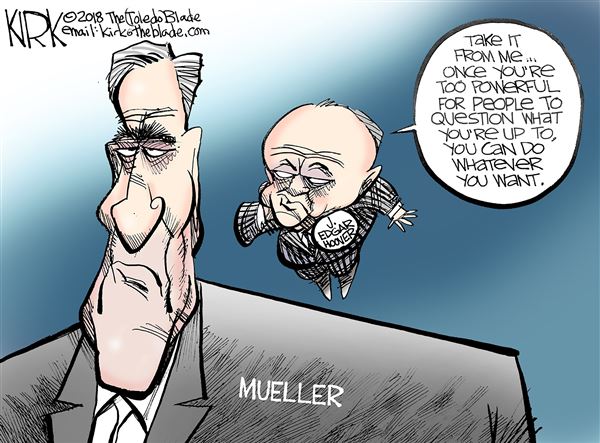

There is no way that Congress can truly prevent the chief executive from removing an inferior executive officer, which is what special counsel Robert Mueller emphatically is.

The push for the bill again shows how Trump's main threat to our constitutional system has been catalyzing a hysterical opposition. That opposition is so freaked out by him that it's willing to throw overboard legal niceties to thwart him.

Hence, much of the #Resistance jurisprudence blocking Trump actions. And hence the astonishing spectacle of US senators advancing a blatantly unconstitutional bill and doing it in a spirit of high moral dudgeon.

The president is the chief executive, and like it or not, Trump is president. This means he runs the executive branch. "I conceive that if any power whatsoever is in its nature executive," James Madison declared, "it is the power of appointing, overseeing and controlling those who execute the laws."

If the president can fire the attorney general -- the ill-used Jeff Sessions attests that he can -- he certainly can fire Mueller. The attorney general is a much more important position than the special counsel.

In compelling Senate testimony, Yale law professor Akhil Amar explained the constitutional problems with the Mueller protection bill. The special counsel by definition is an inferior officer. Otherwise, he has to be confirmed by the Senate, which Mueller wasn't. And if he's an inferior officer, he can be fired.

Amar's point is that Mueller can't be an unconfirmed inferior officer in some respects and a hyper-superior officer in others, enjoying protections from his ouster that even Cabinet officials don't enjoy.

The Mueller protection bill would really represent a return to the constitutional anomaly of the old independent counsel statute. There is a Supreme Court decision that hasn't been directly overruled, Morrison v. Olson, upholding that law.

As Amar noted, though, the decision's credibility is in tatters. Commentators on both the left and right believe that Antonin Scalia's lonely dissent in that case was prescient and sound. By the end of the 1990s and the bout of investigations into Bill Clinton, the independent-counsel statute was allowed to lapse.

The problem with the protection bill in terms of constitutional architecture also gets at the problem with the special counsel. It is perverse that the president is being investigated by his own inferior officer in what ultimately could become an impeachment case.

Yes, there's lots of criminal action in the Mueller probe — the Manafort trial, the various plea deals — but current Justice Department guidance says that the president himself can't be indicted. That means that all Mueller can do regarding the president directly is produce a report that may well instigate congressional action, up to and including an impeachment probe.

This preliminary investigative work should be the work of Congress alone, without the help of someone nominally working for the president he's targeting.

Indeed, if you want investigations of the president that the president can't stop or have influence over, you have to run them out of Congress. With the Democratic takeover of the House, such congressional probes are on their way.

This is a normal working of our system that doesn't require any extra constitutional exertions. Insofar as Mueller has been "protected" to this point, it has been via just this sort of basic political accountability.

Trump has huffed and puffed about Mueller, yet cooperated with his investigation. That could change at any time. Trump only has to decide to fire Mueller once. But it would lead to dire political consequences, and fail to achieve its end of truly shutting Mueller down. If cashiered, Mueller would presumably show up in January as the first witness before Rep. Jerry Nadler's Judiciary Committee and spill all he knows.

That's probably all the protection Mueller needs, and certainly all the protection he can legitimately be afforded.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author