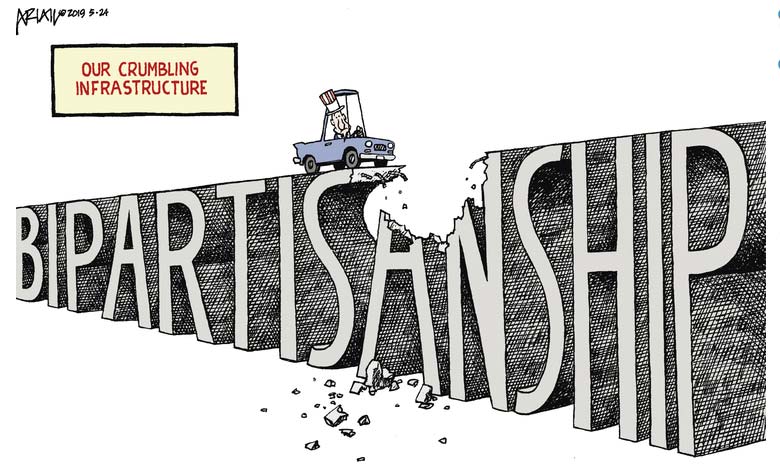

These divisions represent one of the great political challenges of these times, though there appears to be no immediate answer. Politics has become steadily more poisonous and the stakes with each election increase as fears of "the other side" having power course through the electorate. People talk longingly about restoring civility or returning to an earlier time. Little suggests that could happen soon.

There are moments when the light of hope breaks through. Friday's funeral in Baltimore for Rep. Elijah Cummings was a tribute to a politician who fought as hard as he could for the causes in which he believed but made few enemies in the process. But even his funeral conveyed the partisan differences that are today endemic.

Friendships across the political spectrum and within legislative bodies do exist, as Cummings' life showed. But such personal friendships struggle against the deep-seated animosities that now permeate politics. Many Americans decry these conditions and lament that political leaders do not do more to change them. But they contribute to the divisions.

The long-standing bipartisan Battleground Poll, produced by from The Tarrance Group and Lake Research Partners under the auspices of Georgetown University's Institute of Politics, reported last week that almost 9 in 10 Americans say they are "frustrated by the uncivil and rude behavior of many politicians."

About as many Americans say that "compromise and common ground should be the goal for political leaders." At the same time, however, the Battleground Poll found that more than 8 in 10 say they are "tired of leaders compromising my values and ideals" and want leaders "who will stand up to the other side."

The recent Pew report, which is based on nearly 10,000 interviews, underscores the raw antagonism that now exists across political lines, despite broadly expressed desires for civility. The only common ground seems to be agreement that things are terrible. Overwhelming majorities in both political parties say that the extent of polarization is growing worse - and half of them say this is cause for concern.

Another question highlighted one reason there is little space for common ground. More than 7 in 10 Democrats and more than 3 in 4 Republicans say that disagreements with those in the other party go beyond policy differences. They say there is no longer agreement about "basic facts." The gulf is wide because politics is carried out in alternate and competing universes

Political scientists and pollsters have been charting the deepening polarization for many years, highlighting what has been a steady increase in negative perceptions of people who identify with one party to those who identify with the other party. In that sense, what Pew has found does not meet the definition of new news. Nor is it surprising that what Pew found this year is worse than in 2016. The evidence is available on a daily basis. But that's no reason to shrug at what it says and means.

The negative perceptions people have toward those on the other side go well beyond differences over whether taxes should be cut or raise, whether health care should be run by the government or kept in private hands. The hostility is often more elemental.

Here's one example from the Pew report: 55% of Republicans say Democrats are immoral, up from 47% in 2016. Among Democrats, the percentage who say Republicans are immoral has risen from 35% to 47%. Those are remarkable numbers, which explain the kind of discourse, if it could be called that, that is now commonplace on social media.

On some questions, there is rough alignment across the parties - in other words each sees the other negatively, but in about equal percentages. A question about patriotism, however, produced responses that were dramatically asymmetrical. On that question, 63% of Republicans say Democrats are unpatriotic, while only 23% of Democrats say Republicans are unpatriotic. Trump has tapped into this sentiment inside the Republican coalition as a candidate and as president.

Pew uses what is pollsters call a feeling thermometer, which asks people to use a scale of 1-100 to numerically express feelings toward someone or some group. Today, 83% of Republicans and 79% of Democrats give those in the other party ratings that are either "somewhat cold" or "very cold."

Compared to 2016, Republicans are 14 points chillier in their assessments of Democrats, while Democrats are 18 points frostier. Notably, the Pew study says there has been "an especially sharp rise" in the percentage of people who give the opposing party members a very cold rating.

A related measure highlights why this problem can't be solved easily. Today the percentage of people who are both warmer in their assessments of their own party and cooler toward the other side has grown, in both parties. Among Republicans that percentage has jumped from 49% in March 2016 to 75% today. Among Democrats, it has risen from 53% to 71%. People are more dug in.

As in much else in politics today, there are gender and age differences. Men are more likely than women to give those in the other party cold ratings, just as older people are more likely to do so than younger people.

The Pew report amounts to a pre-impeachment snapshot of public attitudes. The survey period ended just before House Democrats opened the impeachment inquiry into Trump's efforts to pressure Ukraine to find damaging information about the 2016 election and about former Vice President Joe Biden and his son Hunter, who sat on the board of a Ukrainian energy company.

There are a few broader conclusions to draw from what Pew's report and the Battleground Poll say about public attitudes. One is that the polarization highlighted in the report did not start with Trump. It has been a long time in the making.

Trump is the most polarizing president in the country's history, measured by his approval rating among Republicans vs. Democrats. But the second most polarizing was Barack Obama and the third most was George W. Bush.

Still, the Pew study underscores what has been evident since the 2016 election, which is that under this president, things have become harsher, more negative and more polarized.

Now comes an impeachment process, a possible vote in the House to impeach a president for only the third time in the country's history, and then a proceeding in the Senate to adjudicate what the House has sent over. All this will further inflame an electorate already divided - one already intensely focused on next year's presidential election.

The end of the Trump presidency, whether that comes in January 2021 or 2025, could reduce temperatures a bit. Realistically, attitudes that have built up over many years and that have intensified under this president could take many more years to unwind.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author