Platforms have wished-and-washed for weeks now about whether Alex Jones of Infowars would lose his pulpit on their services. He's off Facebook and YouTube, and Twitter has put him in timeout, with signs pointing to a permanent suspension from even that free-speechiest of the squadron.

But there's a reason reaching this conclusion took these companies so long and looked so sloppy: They're operating according to a credo that treats societal ills as if they were caused by an irksome line of code.

When Jack Dorsey suggested that "any suspension . . . makes someone think about their actions and behaviors" (and later had to clarify that he doesn't "assume everyone" actually will change), the remark recalled Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg's declaration that there are good-faith Holocaust deniers. That's because both chief executives were trying to fit outliers into frameworks that are designed to work for everyone - that would, in their language, "operate at scale."

This might make sense on a technical level but, in reality, no framework actually works for everyone. The whole wide world is impossible to engineer: Humanity is too messy, and society contains too much ugliness to operate according to any beautiful design. Jones, in other words, does not compute.

And yet Silicon Valley success stories almost always start with the assumption that the biggest of problems can be solved with the most technical of solutions. So when something doesn't compute, from these platforms' point of view, it's time to troubleshoot - to tweak the systems with updated parameters or, in this case, updated terms of service.

That's why companies' response to crisis after crisis has been more and more rules to cover bad behavior that its current policies may miss. At Twitter, "dehumanizing" speech is the phrase du jour (or, judging by the slow timeline the service has suggested, du multiple months).

Layering rules upon rules, however, will never solve the core problem. The platform founders thought they could set up their systems, then step back, and a better world would emerge. Instead, some things improved - and others got worse. All the rules since then have been reactions to deal with those downsides. What the companies haven't done is take a break from trying to troubleshoot and question whether the system itself has a fundamental flaw.

Site creators thought they could remain neutral overseers in perpetuity because they believed their products by their nature provided an unequivocal good: more people in more places seeing more things.

They were wrong.

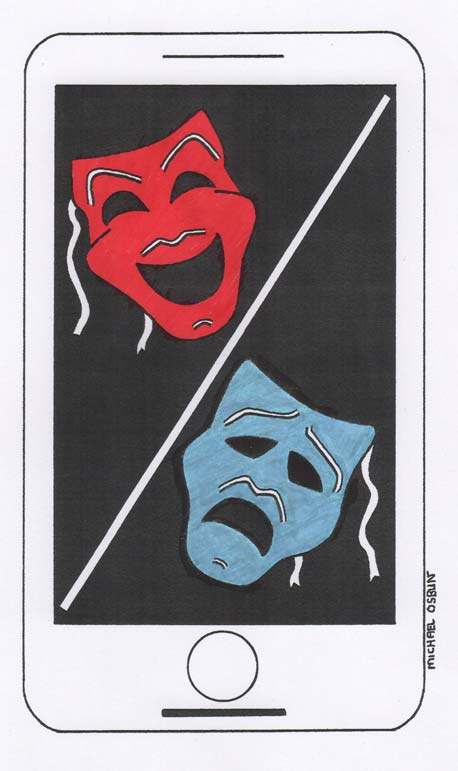

These platforms were supposed to democratize societies and empower dissidents, and they have. But their commitment to unfettered expression can also sometimes let some people shout so loud it's impossible to hear anyone else, in countries where authoritarian regimes have discovered how to harness the same power that once threatened to topple them, or here at home where the harassers can scare the harassed into silence.

And connecting everyone, though it opens doors to plenty that's enriching or enlightening, can also expose people to content that corrupts, from Russian trolls to conspiracy theorists.

It turns out more people in more places seeing more things isn't an unequivocal good. And because it isn't, platforms can't pretend they're neutral overseers any longer - no matter how many haphazard rules they put in place.

Instead, they have to articulate what they want the world to look like beyond the vague objectives that for so long seemed sufficient. Next, they have to rethink their responsibility for helping us get there.

That may mean, yes, more rules, but ideally ones geared toward a clearer purpose. It may also mean altering the algorithms that reward attention-seeking and promote polarization, as Dorsey told The Washington Post on Wednesday he's willing to do. (We'll see.) And it will mean deciding how to handle the outliers that none of those technical changes can capture. It will mean, in other words, making hard choices.

This is a task so tall it's tough to see the top of it, and it's a task that must terrify the executives entrusted with seeing it through. It must terrify them because of the political and legal fallout that comes from accepting a role as a publisher rather than a platform. It must terrify them because of the cost: Meaningfully altering the algorithms that keep people scrolling would require sacrificing the advertising dollars these sites need to survive.

Most of all, it must terrify them because no one else has been able to figure this one out. On the bright side, in Silicon Valley, that sounds like a positive.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Previously:

• 09/17/17: It's finally Google's day of reckoning

• 11/21/17: The rabid response to the nonexistent RIP epidemic

• 11/16/17:

Dems try to reckon with Bill Clinton's alleged sex crimes and fail

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author