Melina Mara for The Washington Post

Melina Mara for The Washington Post

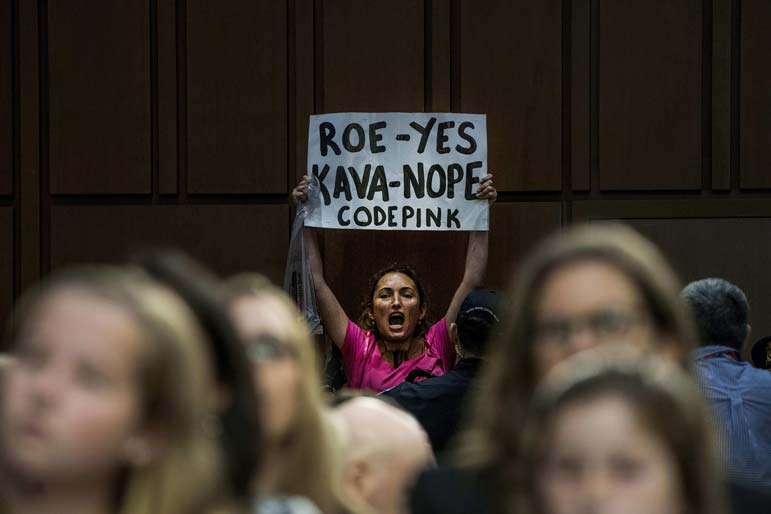

Unless they are very foolish, they must surely realize that news of the arrests might actually turn waverers against them. Their determination to disrupt anyway is a reminder of how far we have fallen from an era when protest was serious business, intended to bring about concrete change.

Let me make clear what I'm not arguing. If Democrats want to engage in dilatory tactics to try to block a vote, they're just playing an old Senate game, not entirely polite but entirely in keeping with the body's convoluted rules and traditions. Similarly, I'm not telling anybody who is passionate about the nomination not to protest. I'm only suggesting that would-be protesters first figure out whether their plan is simply being self-indulgent.

Half a century ago, in his influential article "Towards a Theory of Protest," the economist Kenneth Boulding offered a simple model that has held up well over time. "Protest is most likely to be successful," Boulding argued, "where it represents a view which is in fact widespread in society, but which has somehow not been called to people's attention."

Where the nation is divided, however, matters are "much rougher," because a movement aimed at changing the society tends to give rise to counter-movements. If the tactics of the protesters are sufficiently alarming, "the net result of the protest is to move the system away from the direction in which the protesters want it to move." Therefore, wrote Boulding, when the nation largely disagrees with or is indifferent to the goals of the movement, protest must be carefully designed not to upset or anger those on the fence but to educate them.

I'm not suggesting that the "good old days" were ever pure on this point. Boulding penned his essay when the movement against the Vietnam War was in its infancy, and the protesters of his day might have done better to take his advice. In 1968, activist Jerry Rubin tried to march into a congressional hearing while carrying a toy gun and live bullets. Capitol police hustled him out, and although the event made news, whatever point Rubin thought he was making wound up lost in a welter of condemnation. Then there were the 1971 antiwar protests that sought to shut down the nation's capital. When demonstrators blocked access to congressional offices, Senator Vance Hartke famously lectured them that their actions were making things harder for those (like Hartke) who supported their goal.

That last part matters. Protest isn't the same as self-expression. Protest is theater. The protester is constantly on stage. The purpose of the performance is to advance the cause. Whatever doesn't advance the cause should be avoided.

When I make this point in argument, the usual answer is something like this: "I should be free to say what I want" or "I couldn't live with myself if I stayed silent." Perfectly fair points.

But an unstrategic saying what one wants or an ill-thought-out choice not to stay silent isn't necessarily a contribution to the goal the protester supports. The protester hopes to move society, if ever so slightly, in a particular direction. Boulding's point is that the protester should make a serious effort to calculate the likelihood that the protest will have the opposite effect. If the net effect is likely to be negative, the protest should not take place.

Like many who write about protest movements, Boulding sets up as his exemplar the civil-rights movement. And - also like many - he no doubt romanticizes the movement a bit. Nevertheless, there are lessons here. Consider the arrest of Claudette Colvin for riding in the "white" section of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Colvin's arrest occurred eight months before Rosa Parks', but the NAACP made no attempt to capitalize on the episode, because Colvin was considered (perhaps unfairly) a less-than-suitable icon. Nathan Heller of the New Yorker chronicles the importance of what happened next:

"What is striking about the bus boycott is not so much its passion, which is easy to relate to, as its restraint, which - at this moment, especially - is not. No outraged Facebook posts spread the news when Colvin was arrested.

Local organizers bided their time, slowly planning, structuring, and casting what amounted to a work of public theatre, and then built new structures as their plans changed. The protest was expressive in the most confected sense, a masterpiece of control and logistics. It was strategic, with the tactics following. And that made all the difference in the world."

Heller, as it happens, was reviewing a truly excellent 2017 book by Turkish sociologist Zeynep Tufekci, titled "Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest." Tufekci uses the term "adhocracy" (popularized several decades ago by the futurists Alvin and Heidi Toffler) to refer to protests "without formal structures," where tactics are in effect decided "on the basis of whomever shows up."

The civil-rights protests were carefully structured and coordinated, because the leadership understood that it was engaging in theater and had a sense of how the theater could advance the cause. Disrupting the Kavanaugh hearing, however, looks more like adhocracy. The protests cannot possibly do anything to derail his confirmation, but they can easily make things harder for his opponents. It's unfair to blame everybody who takes a position for the tactics of others who share the same goal, but that's the world we live in, and protest should take account of that fact.

Tufekci, although concerned about the weakness of adhocratic protests, nevertheless sees some strengths. One of these is that adhocratic protest is hard to stop: Even in a dictatorship, there are no leaders to lock up. This elusiveness might constitute a virtue when one is trying to fill the streets with hundreds of thousands in the hope of unseating the dictator. When, on the other hand, one seeks to advance a particular agenda - in this case, the defeat of Kavanaugh - adhocracy can be not only futile but also foolish.

As a scholar who studies the confirmation process, I try to remain agnostic on particular appointments (except when they're friends), but I must confess that a lifetime's work on the topic has left me mystified by the passion that nominations evoke. Nevertheless, the passions are as they are. My only advice is that those who find themselves in passionate opposition stop and ask themselves whether particular tactics are likely to help their cause or constitute potentially harmful self-indulgence.

Stephen L. Carter is the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law at Yale, where he has taught since 1982. Among his courses are law and religion, the ethics of war, contracts, evidence, and professional responsibility. His most recent book is The Violence of Peace: America's Wars in the Age of Obama (2011). He is an author and Bloomberg View columnist.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author