They should have cancelled United Nations week in New York as soon as the news broke that Angelina was divorcing Brad. Did any family more perfectly embody the hopes of that nebulous but uplifting entity, the international community, than theirs?

Angelina Jolie: goodwill ambassador for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Brad Pitt: founder of Not On Our Watch, which seeks to "bring global attention to forgotten international crises." There is a Jolie-Pitt Foundation, which has disbursed tens of millions of dollars to "numerous humanitarian causes around the world." Even the Jolie-Pitt kids are a microcosm of the UN: between them, they have adopted a Cambodian boy, an Ethiopian girl, and a Vietnamese boy. Their three biological children were born overseas, in Namibia and Nice.

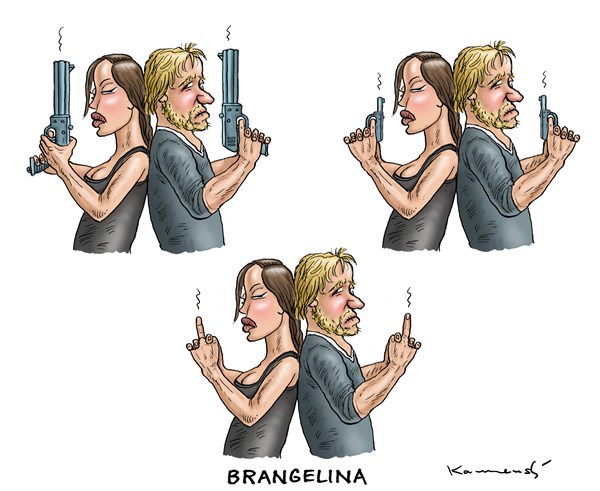

I pass over the reasons for this latest divorce, which will be her third and his second. To me, the end of Brangelina is the stuff of history, not gossip. I had not fully appreciated until last week that the era of globalization was coming to an end. The Jolie-Pitt split caused the scales to fall from my eyes.

The word "global" appeared 18 times in President Obama's tiresomely sanctimonious farewell address to the UN General Assembly. This is what happens to speechwriters after nearly eight years of unceasing bromide production. What begins as aspirant internationalism ends as globaloney.

The disconnect between the president's sermon and the real world could scarcely have been more stark. Yet more terrorist attacks -- this time in New York, New Jersey and Minnesota -- by yet more Muslim immigrants, one of Somali origin, the other an Afghan by birth. Yet another cyber-attack -- this time affecting 500 million Yahoo accounts -- by yet another "state-sponsored hacker."

The conventional wisdom these days is that the rising probability of a Trump presidency is the death knell for globalization. But at this rate the liberal global order -- based as it has been on the ever freer movement of labor, goods, and capital -- will be lying in tiny fragments long before he delivers his inaugural address on January 20.

It may be that Hillary Clinton will stick a pin in the Trump bubble by exposing the yawning chasm of his ignorance in the first of their televised debates Monday night. Yet if she ends up trying to defend globalization, she will lose. All the talking points in the world will not persuade a rising proportion of voters that the stagnation of their incomes, the increase in inequality -- and everything else they don't like about their lives -- are not direct consequences of globaloney. When all is said and done, this rage against the global is the why Trump could win this election.

What can we learn from previous backlashes against globalization? Many people draw comparisons between our own time and the 1930s, but that seems to me the wrong analogy. Better to look back further, to the populist wave of the late 19th century.

Populism took myriad forms in the 1870s and 1880s. In the United States, laws were passed to prevent the Chinese from immigrating. In Bismarck's Germany and the French Third Republic, populism was anti-Semitic, while in late Victorian Britain it was anti-Irish. On both sides of the Atlantic, populists did achieve significant reductions in globalization in this period: not only immigration restrictions, but also higher tariffs. Yet they did not form many national governments, and they did not overthrow any constitutions.

Nor were populists much interested in starting wars; if anything, they lent toward isolationism and viewed imperialism as just another big business racket. In most countries, the populist high tide was in the 1880s. What came next -- in many ways as a reaction to populism, but also as an alternative set of policy solutions to the same public grievances -- was progressivism in the United States and socialism in Europe.

Perhaps something similar will also happen in our time. Perhaps that is something to look forward to. Nevertheless, we would do well to remember that World War I broke out during the progressive not the populist era.

Populists are not fascists. They prefer trade wars to actual wars; border walls to military fortifications. The maladies they seek to cure are not imaginary: uncontrolled migration, widening inequality, free trade with unfree countries, and political cronyism are all things that millions of voters have good reasons to dislike. The problem with populism is that its remedies are in practice counterproductive.

What we most have to fear -- as was true of Brexit -- is not therefore Armageddon, but something more prosaic: an attempt to reverse certain aspects of globalization, followed by disappointment when the snake oil does not really cure the patient's ills, followed by the emergence of a new set of remedies. The populists may have their day, then. But they will end up yielding power to progressive types who will be more congenial to educated elites, but potentially just as dangerous.

Brangelina is dead. Still, something tells me that the Jolie-Pitt view of the world will make a comeback … after Donald Trump has plumbed populism's jolly pits.

Niall Ferguson is a senior fellow with the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

Comment by clicking here.

Previously:

• 09/21/16: The fight isn't going Hillary's way

• 06/28/16: The year of living improbably

• 05/17/16: Welcome to 1984

• 04/19/16: The rise of caveman politics

• 04/05/16: Tay, Trump, and artificial stupidity

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author