But not Hiller: His phone rings 10 times a day with notifications from the summer camp's facial-recognition service, which alerts him whenever one of his girls is photographed enjoying their newfound independence, going water-skiing or making a new friend.

His daughters don't really know about the facial-recognition part, he said. But for him and his wife, it's quickly become a cherished summer pastime, alerting them instantly when the camp uploads its for-parents haul of more than 1,000 photos a day - many of which they end up looking through, just in case.

"I love it. I wish I was with them," he said. "But I at least feel like I know what they're doing."

Facial-recognition software has raised alarms with privacy advocates for its ability to quickly identify people from a distance without their knowledge or consent - a power used increasingly by police and federal investigators to track down suspects or witnesses to a crime. San Francisco and other cities banned the surveillance technology's use by public officials and police earlier this year.

But while that debate rages, the technology has quietly become an accepted, widespread and even celebrated part of Americans' everyday lives. Used to automatically tag photos on Facebook and unlock people's iPhones, the systems have fueled a cottage industry of companies offering to secure school entryways, unlock office doors and identify people at public events.

Now hundreds of summer camps across the United States have tethered their rustic lakefronts to facial-recognition machines, allowing parents an increasingly omniscient view into their kids' home away from home.

The technology has shoved one of childhood's most traditional rites of passage into the Internet age, offering parents a subtle means of digitally surveilling their kids' blissful weeks of disconnect.

The face-scanning photos also have sparked an existential tension at many camps: How do you give kids a safe place to develop their identity and independence, while also offering the constant monitoring that modern parents increasingly demand?

The companies selling the facial-recognition access advertise it as an easy solution to separation anxiety for always-on parents eager to capture every childhood memory, even when those memories don't include them. One company, Bunk1, said more than 160,000 parents use its software every summer.

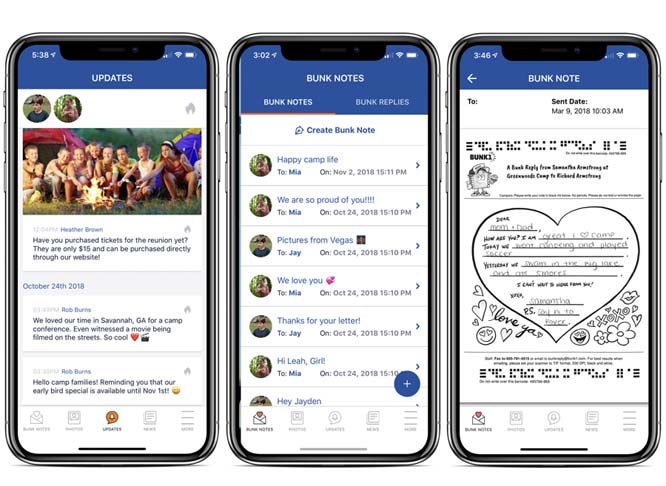

"It's all about building this one-way window into the camper's experience: The parent gets to see in, but the camper's not distracted from what's going on," said Bunk1 president Rob Burns, a former camp counselor himself. "These are parents who are involved in everything their kid does, and that doesn't go away when the kid is at camp."

But some counselors argue that summer camp is one of the few places left in the world where children are expected to unplug - a cocoon for kids to develop real friendships, learn about themselves and get a first glimpse of the freedom and self-confidence they'll carry with them for the rest of their lives. They worry kids will be robbed of that experience if they know it's also being transmitted to family hundreds of miles away.

"How can our kids ever learn to be autonomous when we're always tracking and monitoring them?" said Katie Hurley, a child and adolescent psychotherapist. "We want kids to embrace new experiences: to be great people, expand their social circles and take healthy risks. And we tamp down on them when we're always over their shoulders, saying, 'Don't worry, I'll be watching.' "

No national law regulates facial-recognition software. But Federal Trade Commission regulators said last month that they were considering updates to the country's online child-privacy rules that would designate kids' faces, among other biometric data, as "personal information" protected under federal law. On Thursday, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Facebook users can sue the company for its use of facial recognition technology to identify people in photos without their consent.

Most camp directors said they appreciate that the photos can bring peace of mind to lonely parents worried about their kids' first faraway solo trip. But the photos can also end up perpetuating a cycle of parental anxiety: The more photos the camp posts, the more the parents seem to want - and the more questions they'll ask about their kids.

When a camper isn't smiling or is on the outside of a big group shot, counselors said they know to expect a phone call from back home. Liz Young, a longtime camp director now helping oversee two camps on the coast of New Hampshire's Lake Winnipesaukee, said she now fields as many concerned-parents calls in two hours as she used to get all month - mostly from parents asking about how their kids look on camera, or whether they're being photographed enough.

"If a child's not captured one day, that parent will be ringing: 'Were they being left out? Are they OK? Are they in the infirmary?' And we might just know, oh, they went to the toilet," said Rosie Johnson, a photographer from London working this summer at a camp in the woods of Michigan.

The kids, knowing their parents, will often try to make themselves seen, racing up to her during the day to say their parents need more photos. "A lot of the girls will say, 'A photo a day keeps your mum away,' " she said.

Bunk1, based in New York, has signed contracts with camps who pay an undisclosed fee to start using tools including shared photo galleries and facial-recognition software, which Burns said is used on campers as young as 6 and is offered to parents free of charge.

Another company, Texas-based Waldo Photos, says it offers facial-recognition services to more than 150 summer camps in 40 states for a daily fee, paid by either the camp or parents, of about $1 or $2 per child.

"You get that hit you need as a parent . . . because, selfishly, as a parent, you want to see your child experiencing all of that," Waldo founder Rodney Rice said. More than 40,000 parents have signed up.

Both services ask the parents' permission before scanning: On Bunk1, parents upload a photo of their child to teach the system what to look for, then get regular notifications every time a photo is posted, alongside a question, "Is this your camper?"

Bunk1's "parent engagement platform" also offers families a snail-mail alternative, Bunk Notes, that lets parents use a smartphone app to send a letter, for $1, that a camp staff member will then print out and hand-deliver to their kids. (Several parents said they send a note at least once a day.)

The facial-recognition tool is a technical godsend, Burns said, because it lets some parents zero in on the few camp photos they actually care about - while also surfacing some shots, where their kid might be in the background, that they might have otherwise missed.

Bunk1, whose developers and other employees are based across the U.S., Canada and Colombia, was bought in 2017 by a private-equity-owned holding company called Togetherwork, which specializes in software for groups such as college sororities, sports camps, synagogues, dance studios and dog day-care centers.

The company's terms of service say that a camp or parent who uploads a photo automatically grants Bunk1 "the royalty-free, perpetual, irrevocable, nonexclusive right and license to use, reproduce . . . and distribute" the content worldwide.

Bunk1's privacy policy also says it does not "collect any information" from anyone younger than 13, though the service saves the names and photos of campers much younger than that. "We are not collecting information from campers," he said. "We are collecting information from their parents."

The company, Burns said, stores children's photos securely in domestic data centers and takes families' privacy seriously: One parent, he said, recently called to request that the company delete their account due to concerns over their digital footprint. But he declined to share details about how the data is secured, who designed the software or how it works, citing the need to protect themselves "against any potentially malicious activity."

Common frustrations with facial-recognition software - including that it tends to work better on lighter skin - also plague Bunk1's system, Burns said. But he declined to provide details on accuracy beyond saying there are "some bigger challenges with some skin colors versus others."

Parental anxiety, he said, is a natural camp response, especially from parents sending their kids away for the first time. But he doubted that parents' close involvement or the use of facial-recognition software had "any impact on the psychology of the child."

"If they're looking at photos of their kids while they're at camp," Burns said, "the child doesn't know any different."

Some privacy advocates questioned how the children's facial images would be used, and what would happen to the data if the company were breached, hacked or sold. They also expressed concern that the corporate database of children's faces could one day be tapped for its use in government surveillance.

Bunk1's privacy policy says the company may release information "when appropriate to comply with the law," while Waldo's policy says the company may hand over information to "government or law enforcement officials or private parties" if deemed appropriate "to stop any activity that we consider illegal, unethical or legally actionable."

"Summer camp has traditionally been a place of exploration, a place where one can grow, and a pervasive surveillance system seems completely at odds with those purposes," said Matt Cagle, a technology and civil liberties attorney with the ACLU of Northern California. What would they do, he asked, if immigration officials "gave them a list of children's photos and said, 'Can you search your databases to see if any of the kids are at this camp?' "

Both companies said they had never fielded requests from police or government authorities. Rice said the "privacy hysteria" was "unfounded," and Burns said Bunk1 is not a "pervasive surveillance system," adding, "If it was, hundreds of camps would not use it."

Not every camp is sold on the technology. Camp Encore/Coda, a summer music camp in Sweden, Maine, lets kids and parents exchange simple Bunk1 notes but has declined to use the facial-recognition feature, which camp director Jamie Saltman calls "a little dystopian" and "way too creepy."

But Bunk1's software has nevertheless gained a massive following. Dayna Hardin, the president of CampGroup, which oversees 14 summer camps across the United States and more than 6,000 kids, said the group now employs 35 photographers so "there's pretty much nothing that doesn't get photographed."

One camp, Lake of the Woods and Greenwoods in rural Decatur, Michigan, has four photographers and a social-media director on staff to help push nearly constant updates onto Bunk1, Facebook and Instagram, where recent photos of kids jumping into a lake or firing bows and arrows have netted hundreds of comments and "likes." The facial-recognition system is in its second summer at the camp, and roughly half of all parents of its campers have signed up.

Some of the kids, Hardin said, are so accustomed to constant photography that they barely notice the camera crew. It's the parents, she said, who struggle with the distance - and who are desperate for the reassurance the facial-recognition systems provide. She's had parents tell her they'll pull off on the side of the road the minute the photos go online.

"They're growing up in this digital world, and cutting the umbilical cord is really hard," Hardin said - speaking of the grown-ups, not the kids. "Today's parents are used to getting six messages a day about their kids since the time they were 6 months old."

That's made it tough on people like Johnson, the 21-year-old photographer who moved from London to work at a camp as part of a summer job-exchange program. She keeps a tightly scheduled, paper itinerary of the day's activities - a big group shot at the morning flag ceremony is more efficient for getting lots of faces than, say, a few kids at arts-and-crafts - but she still ends up walking about 13 miles a day trying to get everyone on camera.

The photos she and her colleagues upload go online the next day, and post at noon on the dot - a time she knows all too well, because parents regularly watch their phones for the notifications to arrive. The close scrutiny from parents has made her that much more careful about the experiences she captures on camera. When kids frown for a photo, even if they're joking, she'll remind them that their parents are watching and worrying - and, sometimes, judging the camp based on what they see.

Some of that heavy monitoring, camp directors note, is financially motivated: Parents shelling out $10,000 for an eight-week summer camp tend to want to see where that money has gone. But there is a competitive element, too, the directors said: Some parents race to share the photos on social media as a way to curate their kids' childhood and offer visual evidence that their family is worth envying.

Hurley, the child psychotherapist, said the summer-camp face scans and technologies like them can "feed this cycle of anxiety in families, because the parents never feel calm and safe and that things are OK, and that bleeds down to the kids."

The photos, Hurley worried, could inflame new tensions for kids hitting the age - generally, in the pre- and early teens - when they can start to feel awkward about all the photos their parents post. But they can also foster unease for kids questioning how much of their emotions and internal lives they're comfortable sharing in every moment, even when they're far from home.

"Parents right now are conditioned to really worry if their kids are having fun and if they're happy - which is absurd, because they send them to these amazing camps where they're practically guaranteed to have fun," she said. "This idea where you have to be happy all the time: That's not real, and yet that's what we're chasing and what we're looking for when we want all these pictures all the time."

Kate Lemay, the executive director of the YMCA of Greater Boston Overnight Camps, which runs three boys' and girls' camps in New Hampshire, said she appreciates that the photos can help give parents a sense of trust in where their kids are staying. She worked with Bunk1 to help develop a Web seminar for parents to help them "manage expectations" and deal with anxiety around the experience, including how many photos they'd see. Counselors, she said, also often help kids learn to deal with homesickness and other "instantaneous emotions" that often lead them to reach for their cellphone.

But still, she struggles over how much access to their kids is too much. "As much as it is a reassuring platform, some days I wonder if this is something we should be doing, or if it's making it worse," she said.

"There's the contradiction of these really old-fashioned summer camps with no electricity in the cabins, no cellphones . . . but the parents can check in daily to look at the expressions on their kids' faces," she added. "Part of childhood development is: It isn't always 100 percent smiling."

Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author