Marvin Joseph for The Washington Post

Marvin Joseph for The Washington Post

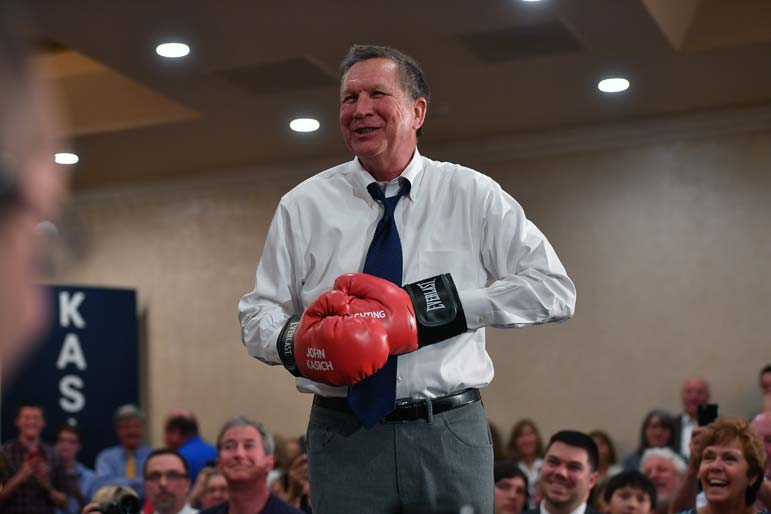

For a guy who insists he's not running for president in 2020, Ohio Gov. John Kasich sure spends a lot of time denying it.

"I don't have any plans to do anything like that. I'm rooting for [President Trump] to get it together," Kasich told Jake Tapper on CNN's State of the Union this past weekend. "We all are. I mean, we're only, like, seven months into this presidency."

Tapper's question was prompted by this tweet, four days earlier, from The Today Show's Willie Geist: "Sources close to ‪@JohnKasich tell me, after Charlottesville, there is growing sense of "moral imperative" to primary Trump in 2020."

Maybe Kasich will indeed sit it out in the next presidential election. But he'll have to do a better job of convincing the hometown crowd. The Cleveland Plain Dealer wryly observed that Kasich "continues his run as a CNN commentator", adding: "Almost as if he is still running for president, not governor of Ohio."

So what if Kasich were to take on Trump, assuming the President seeks re-election, for the Republican nomination?

It wouldn't exactly be a historical departure: five of the six presidents who served between 1968 and 1992 faced an intraparty uprising.

What those challengers have in common: they all failed.

To take Kasich seriously as a threat to Trump in 2020 is to place him in the same league as the two biggest primary challenges in recent times: Ronald Reagan in 1976 and Edward Kennedy in 1980.

(I'm not including Pat Buchanan in 1992 because, at no point, did he win a major state or come within striking distance of enough delegates to get the job done.)

What Reagan and Kennedy had that Kasich presently does not:

Ideology. Reagan ran as the conservative alternative to President Ford, just as Kennedy tried to reawaken the Democrats' liberal base. They also tapped into dormant legacies (for Reagan, the Goldwater crusade of a dozen years previous; for Kennedy; the martyrdom of his slain brothers).

Notice the use of the term "moral imperative" in the Geist tweet. It suggests the driving force behind a Kasich campaign would be the notion of Trump as unfit to serve. That's music to the ears of the #nevertrump crowd, plus a lot of consultants who worked on losing presidential campaigns in 2016.

But is it enough to spark a party insurrection?

Geography. Reagan gave Ford fits in the South, the West and the Great Plains States. Kennedy bested Carter in California and its southwestern neighbors, plus the New York tri-state area and parts of his native New England.

On paper, Kasich would seem positioned to do well across the same Midwestern stretch that was a key to Trump's win last year - remember, Kasich's presidential pitch was a blue-collar guy raised in Western Pennsylvania steel country.

But in 2016, that didn't translate to delegates. Kasich carried the Ohio primary by 11 points, winning the state's delegation. However, he finished third in Michigan, just one half of a point behind Texas Sen. Ted Cruz and a dozen points behind Trump.

In Wisconsin, Kasich was a distant "show" - 21 points behind Trump, 37 points Cruz. In all, Kasich earned delegates in only four of the 20 states that voted after Ohio.

The dynamics would be different were the 2020 primaries to be a head-to-head duel between Kasich and Trump (remember, Trump couldn't get past 36.5%, in a multi-candidate field, in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, which would be at the heart of Kasich Country). But if 2016's an indicator, Kasich struggles to do well beyond the Ohio border.

There is one other scenario to consider: the Republican Party flipping its Whig.

Translation: could Trump run afoul of the same trouble that did in an American president nearly 175 years ago?

The winner in the election of 1840 was William Henry Harrison, the first of four Whig presidents. His running mate and successor when Harrison died just a month and six days after taking office: John Tyler, a Democrat-Republican turned states' right southerner with little in common with the Whig Party - dubbed "His Accidency" (not a compliment) for the fortuitous nature of his earning the job.

Tyler and the Whig Congress had their productive moments: they worked out a tariff bill to protect northern manufacturers; the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, signed in 1842, ended disputes dating back to the Treaty of Paris and the end of the Revolutionary War.

But politically, there was big trouble.

Unable to reach agreement on federal banking policy, Tyler and the Whigs ended up in divorce court: the party expelled the president; Congress attempted to impeach him.

What was left of the Whig Party - Democrats captured the House in 1842, with the Whigs narrowly holding on to the Senate - rallied behind Henry Clay, who'd go on to become the party's nominee in 1844 in the race against Democrat James K. Polk.

As for Tyler, he was a man without a party. His play in 1844: resurrect a Democratic-Republican Party that had run its course by the end of the Monroe presidency 20 years previously and take on the role of a potential spoiler - targeting a handful of swing states until he received the promise that a Polk Administration would follow through on Texas annexation (Tyler had reached an agreement with the Republic of Texas but lacked the Senate votes to ratify a treaty).

How this applies to Trump, other than his detractors insisting he too is an accident of history, if not something darker and more conspiratorial? Like Tyler, he's an affiliate of a party (with a history of shifting allegiances) but not a charter member. Like Tyler, he could face a midterm scenario that has his party losing one chamber of Congress.

And, like Tyler and the Whigs of the 1840s, what happens if the Trump agenda clashes with that of congressional Republicans (which seems less likely now that Steve Bannon has returned to the world of online publishing)?

Impeachment is the option that the media love to discuss. But here's the catch: Trump is more popular with GOP-leaning voters than is the Republican Congress. According to this poll, Trump's lost 6 points with this block from June to August (from 81% approval to 75%); the GOP Congress has fallen from 68% approval to 54% approval (disapproval climbing from 32% to 46%, while Trump's has grown from 19% to 25%).

Back in Ohio, what that should tell John Kasich: conditions between the Republican president and the Republican Congress may worsen if the productivity continues to languish, or there's a major policy rift.

But for now, we're a long way from the party flipping its Whig in 2020.

Comment by clicking here.

Bill Whalen is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, where he studies and writes on current events and political trends. In citing Whalen as one of its "top-ten" political reporters, The 1992 Media Guide said of his work: "The New York Times could trade six of its political writers for Whalen and still get a bargain." During those years, Whalen also appeared frequently on C-SPAN, National Public Radio, and CNBC.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author