In an age when political disputes are increasingly accompanied by calls to lock up one's opponents, the court seems poised once again to scale back the use of criminal remedies to address political misconduct. In this case, it would be a welcome step.

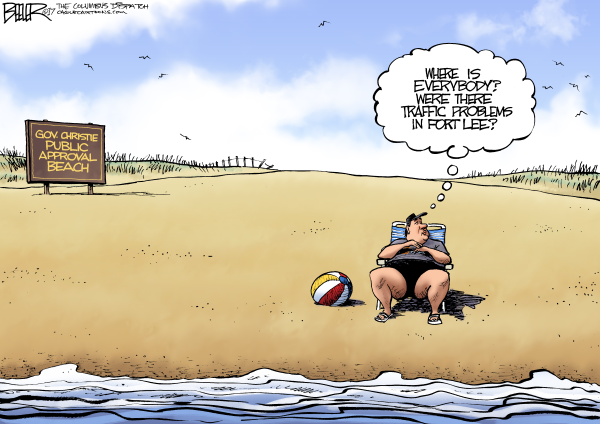

In September 2013, officials at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey shut down two access lanes to the George Washington Bridge, creating crippling traffic jams in Fort Lee, New Jersey. They did so under the pretext of conducting a "traffic study," but the real purpose was to punish the Democratic mayor of Fort Lee for refusing to endorse the reelection bid of then-Gov. Chris Christie, a Republican.

The four days of gridlock were more than just a headache for commuters; among other things, the scheme endangered public safety by making it difficult for police and paramedics to reach those needing assistance.

The scandal caused significant political damage to Christie, who once had presidential aspirations. But the consequences were more than just political for Port Authority official Bill Baroni and for Bridget Anne Kelly, an official in Christie's administration: Federal prosecutors indicted them for their roles in orchestrating and carrying out the scheme.

The defendants didn't personally profit from the scheme. There was nothing inherently illegal about closing the lanes, which the Port Authority had the power to do. The government's legal theory is that Baroni and Kelly caused the Port Authority to pay a few thousand dollars in salaries to employees involved in closing the lanes and deprived the agency of its right to control the lanes and toll booths.

This was fraud, prosecutors argue, because while doing so, the defendants lied to conceal their true political motives.

Baroni and Kelly were convicted and sentenced to prison terms. Their conduct was deplorable, to be sure, but should it be a federal felony? The Supreme Court is likely to say no.

In a series of cases stretching back more than three decades, the court has repeatedly pushed back against federal prosecutors using criminal law to punish political misconduct. Prosecutors in such cases often employed a theory known as honest services fraud, charging a defendant with depriving the public of its right to the fair and honest services of government officials, even when the government suffered no financial harm.

But in 1987, the Supreme Court struck down honest services fraud as too vague, saying it impermissibly allowed federal prosecutors to set "standards of good government for state and local officials." Congress reinstated the theory the following year, but in a 2010 decision, the court stepped in again, limiting honest services fraud to only bribery and kickbacks - classic, clear-cut corruption.

The Bridgegate defendants argue that prosecutors have tried to make an end-run around these precedents. The government couldn't charge honest services fraud directly because no bribes or kickbacks were involved. So, the defendants argue, prosecutors dressed up what is really a flawed honest services fraud theory as traditional money fraud, focusing primarily on the relatively trivial cost of the salaries of employees who carried out the scheme.

As the defendants pointed out in their petition to the Supreme Court, nearly every case of alleged political misconduct will involve some use of government resources. If that's enough to prosecute a politician who lies about the true motives for his or her actions, then the floodgates the court has been trying to keep closed for more than 30 years will burst wide open.

Consider the recent controversy over adding a question about citizenship to the 2020 Census. The Supreme Court held last week that Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross's purported reason for wanting to add the question appeared "contrived." Tremendous resources, including Commerce Department employee salaries, were no doubt devoted to this failed effort.

Put aside whether Ross may have lied to Congress or committed other offenses; if he merely lied to the public about his true rationale, should that alone be the basis for a criminal prosecution? Some might respond, "Yes! Lock him up!" But we should be reluctant to grant federal prosecutors this kind of power to police political acts. Partisans are quick these days to seek criminal remedies for any bad behavior by a political opponent. But there is a great deal of conduct that is sleazy, reprehensible or just politics as usual that is not criminal - and should not be. For better or worse, politicians constantly conceal their true motives. They engage in "spin." They may work to favor political allies or donors or to harm political opponents, all while claiming to act only in the public interest. But the remedies for such political deceptions generally have been at the ballot box, not in a criminal courtroom.

In the Bridgegate case, the Supreme Court is likely to affirm that principle once again.

Every weekday JewishWorldReview.com publishes what many in the media and Washington consider "must-reading". Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Eliason teaches white-collar criminal law at George Washington University Law School.

Previously:

• 01/28/19: There's evidence of collusion everywhere, but is it criminal conspiracy?

• 01/18/19: Barr is right about releasing Mueller's report

• 01/16/19: Don't subpoena Trump's interpreter

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author