Former Vice President Joe Biden, who stakes his candidacy on the claim that he is most viable in a matchup against Trump, had a bad night. Those who did well, including Sens. Kamala Harris of California on Thursday and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts on Wednesday have their own general election vulnerabilities.

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., as the only self-professed Democratic socialist among the candidates, has similar potential liabilities for a general election. Few among the rest of the enormous field have even left a mark on the voters, with South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey possible exceptions.

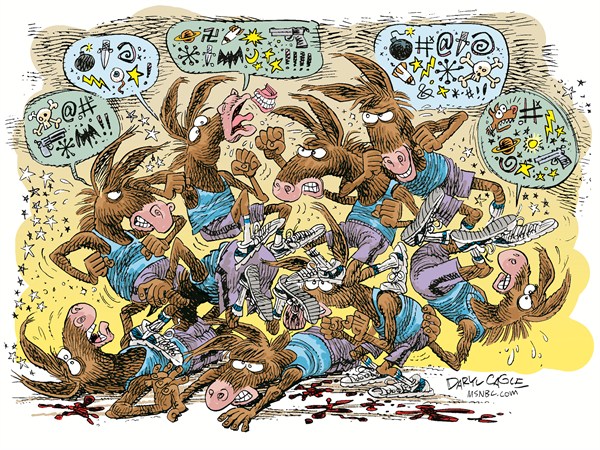

The two nights and four hours of debating also highlighted the leftward movement of the Democratic Party and the degree to which many of the candidates are more focused on appealing to their most liberal constituent groups' priorities, rather than addressing the lives and needs of the mass of voters with whom they must connect in a general election.

Based on the two nights, the Democrats stand for decriminalizing crossing the border and health coverage for undocumented immigrants, while being divided on the crucial question of whether private health insurance stays or goes. The Trump campaign officials who were circulating around Miami during the week looked pleased.

The sharp exchange between Harris and Biden over the former vice president's opposition to mandatory school busing early in his political career and his recent comments about working together with segregationist senators was the most electric moment of the two nights. It exposed the broader challenge for the candidate who has topped virtually all the national and state polls.

Biden says the campaign should not be about the past, and he came into the debate hoping to talk more about where he would take the country than where he has been over four decades in public life.

His advisers have long hoped that voters will judge him not by a selective reading of his record, since there are any number of issues scattered along that lengthy timeline, but by the totality of that record.

If that is the case, then the strength Biden has shown in the early polls, with support across various demographic groups in the party, could prove durable. Any number of African American voters in South Carolina told my Post colleagues that they were not particularly bothered by what Biden had said about working with segregationist senators and maintained their affection for him. Will Harris' attacks change any of that? The answer will become apparent with future rounds of polling.

Biden's campaign has played out on two tracks, one positive, one not so positive. On the plus side, he has made the case that he better than any other Democrat can win in the states that will likely decide the general election, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin, and that he can hold Minnesota and perhaps compete in Iowa.

But the "electability" rationale depends on a candidate living up to his own billing and performing at a level that gives Democratic voters confidence that he or she can prevail against a skilled, ruthless and dominating president who has shown the ability to control and direct the political conversation with a few tweets or comments in the Oval Office or from the White House South Lawn.

On this question, the issue of candidate performance, Biden has raised questions about himself. Over a period of weeks, a series of controversies have disrupted his campaign - from the issue of his touchiness with women, to a reversal on getting rid of the Hyde Amendment on abortion, to the issue of race to his comments about the southern segregationists.

Both in Thursday's debate and at times along the campaign trail, Biden's campaign skills have been called into question. Some moments he is the Biden long seen on the public stage: sharp, crisp, engaging, indignant, emotive. At other moments he appears rusty and still trying to get his campaign legs. Long criticized for being too windy, he twice cut himself off during Thursday's debate, at one point stopping by saying, "My time is up."

That echoes the argument thrown at him by fellow debater Rep. Eric Swalwell of California: It is time for Biden's generation (and Sanders is part of the same generation) to pass the torch to younger Democrats. Swalwell reminded the audience that Biden had said exactly that as a young senator running for president in 1988.

"I'm still holding onto that torch," Biden replied to Swalwell. No campaign operates flawlessly; all encounter obstacles. It's the best that surmount those hurdles and move forward.

Biden's position has been weakened. But who has been strengthened? Who can make a stronger general election case? Who has more attributes and fewer vulnerabilities?

Harris certainly was helped by the debate. Her aggressive criticism of Biden could be a proxy for her assertion that she would best be able to prosecute the case against Trump. She is a political talent, but so far in the campaign - and say those who watched her as attorney general in California - she has applied those talents unevenly.

She was bold in taking on Biden, but she has a cautious streak as well. When Sanders proposed giving terrorists or sex criminals in prison the right to vote, she was asked whether she agreed. The answer for anyone contemplating a general election seemed obvious - to say no. Instead, Harris she said she was open to "a conversation."

She has struggled from the early days of her campaign to clear up questions about what her support for Medicare-for-all means for the future of the private insurance industry. It flared again after Thursday night when she raised her hand to say she was prepared to get rid of her private insurance in favor of a government health-care plan. She later said she misunderstood the question.

Her attack on Biden gave her the post-debate headlines and buzz. But in a multicandidate field, attack politics is unpredictable. The person on the attack can get hurt as well. That was one reason many strategists anticipated fewer fireworks in Miami. The risks can outweigh the rewards, especially when dealing in the realm of racial politics.

Warren stood out on the first night of the two rounds of debating, in part because she was able to encapsulate the mountain of policy initiatives she has issued into a general message about an economy that works for some - the wealthiest and the biggest corporations - but not for all others. That remains a strength.

What is in question is whether her campaign strategy - that in response to the Trump's base-driven campaign, Democrats must run a similar and potentially divisive campaign to generate enthusiasm that was lacking in 2016 - is the best course.

She and her team are prepared to take that case to Democratic voters, but is polarizing the electorate further the right course? Biden, calling for a campaign that would lead to a reduction in partisanship and an openness to working with and compromising with Republicans, is offering the direct opposite.

Much is being made of the first round of debates - too much no doubt. This is still a time when most voters are not paying sustained attention, though the ratings for the two nights were strong. The size of the field shows that candidates believe anything can happen in the fight for the nomination. The events in Miami suggest this will be a long battle, among a number of candidates, before it is settled.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author