These periodic, now-inevitable freak-outs are a sad by-product of our country's drift away from political rule and over-investiture of power in the judiciary. But happily, the most urgent constitutional challenge of our time needn't wait on a court ruling. Each political branch of government has the constitutional authority needed to fix it.

I refer, here, to ending birthright citizenship.

The notion that simply being born within the geographical limits of the United States automatically confers U.S. citizenship is an absurdity - historically, constitutionally, philosophically and practically.

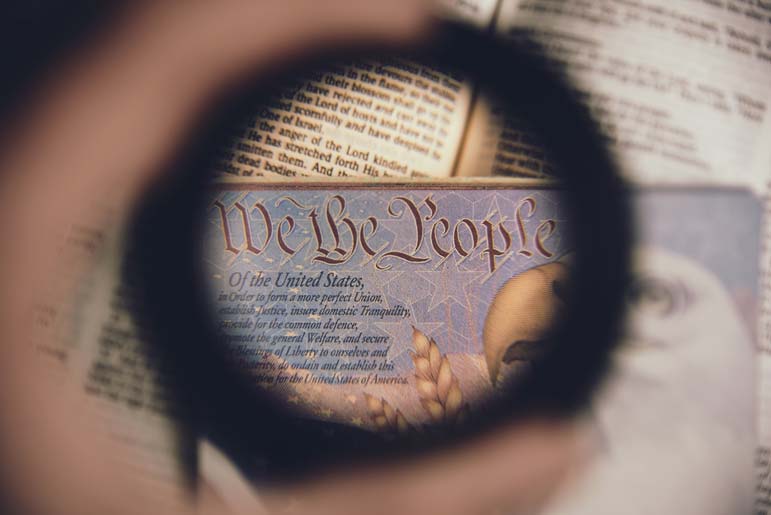

Constitutional scholar Edward Erler has shown that the entire case for birthright citizenship is based on a deliberate misreading of the 14th Amendment. The purpose of that amendment was to resolve the question of citizenship for newly freed slaves. Following the Civil War, some in the South insisted that states had the right to deny citizenship to freedmen. In support, they cited 1857's disgraceful Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, which held that no black American could ever be a citizen of the United States.

A constitutional amendment was thus necessary to overturn Dred Scott and to define the precise meaning of American citizenship.

That definition is the amendment's very first sentence: "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside."

The amendment clarified for the first time that federal citizenship precedes and supersedes its state-level counterpart. No state has the power to deny citizenship, hence none may dispossess freed slaves.

Second, it specifies two criteria for American citizenship: Birth or naturalization (i.e., lawful immigration), and being subject to U.S. jurisdiction. We know what the framers of the amendment meant by the latter because they told us. Sen. Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, a principal figure in drafting the amendment, defined "subject to the jurisdiction" as "not owing allegiance to anybody else," that is, to no other country or tribe. Sen. Jacob Howard of Michigan, a sponsor of the clause, further clarified that the amendment explicitly excludes from citizenship "persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, [or] who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers."

Yet for decades, U.S. officials - led by immigration enthusiasts in and out of government - have acted as though "subject to the jurisdiction" simply means "subject to American law." That is true of any tourist who comes here. The framers of the 14th Amendment added the jurisdiction clause precisely to distinguish between people to whom the United States owes citizenship and those to whom it does not. Freed slaves definitely qualified. The children of immigrants who came here illegally clearly don't.

Those framers understood, as did America's founders, that birthright citizenship is inherently self-contradictory. A just government in the modern world rests on the social compact, a freely entered agreement among free citizens. That compact's scope and authority extend only to those who have consented to its terms and whose membership has been consented to by all other citizen-members. A compact that anyone can join regardless of the wishes of its existing members is not a compact. As President Donald Trump likes to say, "If we don't have a border, we don't have a country."

Some will argue that the Supreme Court has already settled this issue, establishing birthright citizenship inUnited States v. Wong Kim Ark. But this is wrong. The court has only ruled that children of legal residents are citizens. That doesn't change the status of children born to people living here illegally.

Practically, birthright citizenship is, as Erler put it, "a great magnet for illegal immigration." This magnet attracts not just millions of the world's poor but also increasingly affluent immigrants. "Maternity hotels" for pregnant Chinese tourists advertise openly in Southern California and elsewhere. Fly to the United States to have your baby, and its silly government will give him or her American citizenship!

It is no wonder that citizens of other countries take advantage of our foolishness. Life is still better here than almost anywhere else, including rising China and relatively prosperous Mexico. The wonder is that we Americans continue to allow our laws to be flouted and our citizenship debased.

The problem can be fixed easily. Congress could clarify legislatively that the children of noncitizens are not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, and thus not citizens under the 14th Amendment. But given the open-borders enthusiasm of congressional leaders of both parties, that's unlikely.

It falls, then, to Trump. An executive order could specify to federal agencies that the children of noncitizens are not citizens. Such an order would, of course, immediately be challenged in the courts. But officers in all three branches of government - the president no less than judges - take similar oaths to defend the Constitution. Why shouldn't the president act to defend the clear meaning of the 14th Amendment?

Judges faithful to their oaths will have no choice but to agree with him. Birthright citizenship was a mistake whose time has gone.

Michael Anton is a lecturer and research fellow at Hillsdale College and a former national security official in the Trump administration.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author