Polls show that the public is worried about climate change, but that doesn't mean that it is anymore ready to bear any burden or pay any price to combat it.

If President Donald Trump claws his way to victory again in Pennsylvania and the Upper Midwest, his path will likely go through abortion and climate change, two issues on which the Democrats are most inflamed, confident in their righteousness and willing to embrace radical policies that appeal to their own voters much more than anyone else.

Joe Biden, the relative moderate, is subject to these forces. He dumped his longtime support for the Hyde Amendment prohibiting federal funding of abortion last week and released a climate plan that, even if more modest than the "Green New Deal" (a low bar), is clearly derived from it.

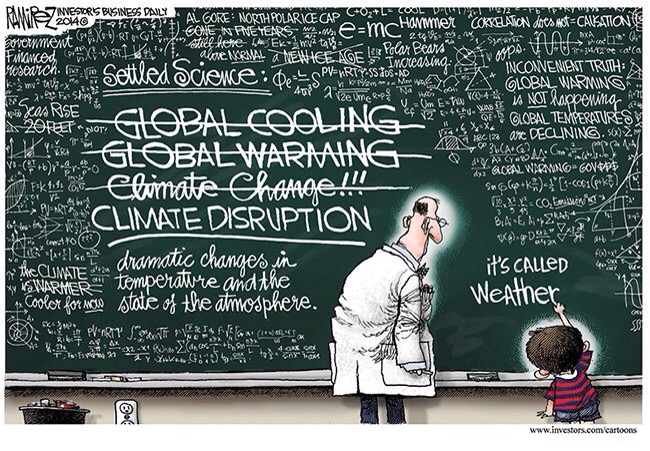

Climate is a watchword among the Democratic presidential candidates — and an enormous downside risk. Once everyone on your own side agrees about an issue, and once you are convinced that you are addressing a planet-threatening crisis that will become irreversible in about a decade's time, prudence and incrementalism begin to look dispensable.

There's no doubt that climate is a top-tier issue for Democrats. In a CNN poll, 96 percent of Democrats say it's very important that candidates support "taking aggressive action to slow the effects of climate change." Its doubtful that mom, baseball and apple pie would poll any higher.

It's also true that the public is adopting climate orthodoxy. According to a survey by climate change programs at Yale and George Mason, 70 percent believe that climate change is happening, and 57 percent believe that humans are causing it.

It's easy to overinterpret these numbers, though. While a big majority of Democrats see climate change as a problem, an NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll found only 15 percent of Republicans and — more important — just 47 percent of independents do.

Of course, saying climate change is a problem doesn't cost anyone anything. An AP/University of Chicago poll asked people how much they were willing to pay to fight climate change, and 57 percent said at least $1 a month, or not even the cost of a cup of coffee at Starbucks.

The political experience of other advanced democracies is a flashing red light on the climate. In Australia last month, the opposition lost what was supposed to be "the climate change" election, against all expectations. In May, the New York Times ran an article headlined, "Australia's Politics May Be Changing With Its Climate."

Polling showed that about 60 percent of Australians called climate change "a serious and pressing problem," and thought the government should address it "even if this involves significant costs."

It turned out that it was one thing to tell that to pollsters and another to vote to make it happen. The opposition promised a 45 percent reduction in carbon emissions with no serious pain while the conservative governing coalition focused on the cost, and won.

In France, gas and diesel hikes as part of a government plan to reduce carbon emissions by 75 percent sparked the yellow vest movement in car-dependent suburbs and towns, and had to be ignominiously reversed. It's not as though French President Emmanuel Macron isn't committed — the climate is one of his signature issues.

The politics of climate change will be problematic for the duration, for several reasons. The voters most opposed to the costs of climate action tend to be the kind of "deplorables" most easily dismissed by center-left parties at their own peril: voters in rural Queensland in Australia, economically distressed residents of unfashionable rural and semiurban areas of France, working-class voters in the Rust Belt in the U.S.

The real felt urgency of climate change will not, anytime soon, match the rhetoric of the advocates. There's currently an effort to make every U.S. drought or flood, tornado or hurricane, a symptom of an alleged climate emergency. This approach may pay some dividends since there's always extreme weather, but it hardly reflects a careful accounting of the data.

According to Benjamin Zycher of the American Enterprise Institute, the Palmer Drought Severity index doesn't show a trend since 1895 and the pattern of U.S. flooding over the past century doesn't track with global warming; there's been no trend in U.S. tornados since 1945, and little trend in tropical storms and hurricanes since the early 1970s.

Bearing real costs for the sake of the climate will always be a sucker's game for any one country so long as there isn't a global regime mandating emission reductions (and, thankfully, there isn't anything remotely like the political will for such a regime). It was supposed to be a disaster when Trump pulled out of the Paris accords, but G-20 countries haven't been on pace to meet their goals regardless.

Finally, whatever the costs, no one is going to feel any climate benefits anytime soon, or likely ever. The supposed upside of plausible policies adopted by the U.S. would be minuscule changes in the global temperature decades from now. Even the wildly radical Green New Deal wouldn't make much difference.

All this should counsel caution rather than apocalyptic rhetoric and policies, although Trump has every reason to hope it doesn't.

Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author