The prelude to Tuesday's meeting has been anything but smooth. The summit was announced suddenly, catching even some of the president's advisers by surprise. Two weeks ago, it was abruptly canceled. Was that because of presidential pique or an example of shrewd, strategic gamesmanship? Whichever, the event was quickly put back on the calendar. A flurry of meetings since has set the stage for Tuesday.

The goal of this meeting has not shifted. The president wants North Korea to agree to complete, verifiable, irreversible denuclearization. But if the goal hasn't changed, the expectations have. Trump once seemed to suggest it could all happen in a single meeting between the two leaders, the inverse of how such negotiations normally take place. He now concedes that Tuesday's summit, if successful, will be only the first step in a lengthy process.

Questions persist about the president's readiness. Trump says he has been preparing for this "all my life." He also claims that little preparation is needed for this event. Those who have been through such events scoff at that notion. The president's confidence no doubt stems from the fact that he has been in countless negotiations as a businessman and real estate developer. But he has never been involved in anything of this complexity and consequence.

Tuesday's summit could be the kind of event the president loves, with a worldwide audience, ratings through the roof and the focus of everything and everyone on him (and the North Korean dictator). It will be a far different environment than what Trump has spent the weekend doing, which is meeting with other leaders of the Group of Seven nations, as one of equals, and in this case as someone whose trade policies have created rifts in relations and sore feelings. On Tuesday, he will happily command the entire stage.

The president has said frequently he's prepared to walk away if things don't go well, but he is invested in making this summit a success. Given his penchant for hyperbole and exaggeration, it is easy to envision the smiles and handshakes and grandiose rhetoric that will flow at the beginning and end of the talks.

Reality is something else. This isn't the first time the North Koreans have been in discussions over their nuclear ambitions nor would this be the first agreement they've made with other nations. Their word has proved hollow in the past. As Leon Panetta, the former CIA director and secretary of defense, put it: "It's difficult to trust anything that is said" at the summit. "The first premise when you walk in that room is 'You don't trust him (Kim).'"

At the same time, long-term success in eliminating North Korea's nuclear program could depend on whether the two leaders are able to develop a working relationship of mutual trust that would infuse subsequent negotiations between their aides and advisers as a process unfolds. For the president, this could be more difficult than it seems.

He has shown an ability to develop seemingly good relationships with some world leaders, and then to undermine them with unexpected words or actions. Trump's judgment of others often is on the basis of what's good for Trump. Witness what has happened in recent days with French President Emmanuel Macron, with whom he has had a virtual love affair, and with Canadian Prime Minister Justine Trudeau, due to the disputes over the administration's trade policies.

It could be years before anyone can fully judge whether the Singapore summit put the two countries on a path to success. Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who has and will play a key role in these nuclear negotiations, have been firm that Kim Jong Un must agree to eliminate his nuclear weapons capability. Given his criticism of and later withdrawal from the nuclear agreement with Iran negotiated during the Obama administration, the president has set a high bar for himself with North Korea. He must deliver an airtight agreement.

If Tuesday marks only a beginning, how can the meeting be evaluated? Those with experience in national security issues believe one measure of progress, beyond what can be observed about the Trump-Kim personal chemistry, will be whether there is a framework that includes an explicit agreement by the North Koreans to denuclearize; a willingness on their part to constrain their ballistic missile program (and not just long-range missiles that could reach the United States but also those that threaten its immediate neighbors); and a commitment to an intrusive verification system.

In return, the United States could offer help in produce a peace treaty between North Korea and South Korea, pledge not to invade North Korea, hold out the possibility of diplomatic relations if North Korea lives up to its promises and likely offer assurance of economic assistance at some point in the future. All of that might seem in the realm of the normal and expected in such a negotiation, but it is important to remember that with this president, the normal and expected are not always in his vocabulary.

Trump's attention span is notoriously short, and he is capable of constant self-created distractions, as his morning tweet storms about special counsel Robert Mueller's Russia investigation are a regular reminder. Does he have the patience and commitment to see through what could be a long negotiation, and one that will have setbacks along the way?

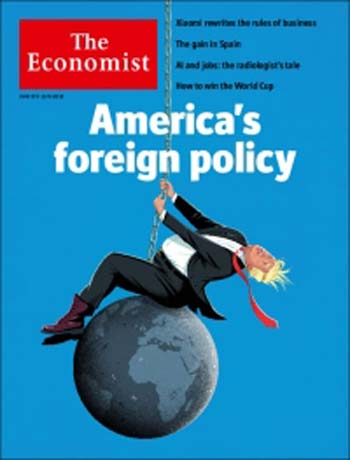

The reality is that, so far in his presidency, Trump has done more to upend the norms in foreign policy than to reinforce them. Meanwhile, he has yet to deliver on new arrangements that put the United States in a stronger position. As the New Yorker's Susan Glasser recently wrote, "Trump is a much better dealbreaker than dealmaker."

Beyond the Iran nuclear agreement, he withdrew the United States from the Trans Pacific Partnership and the Paris climate agreement. His trade policies have caused ruptures with various other countries and are influencing upcoming Mexican elections.

His policies and his words have generated friction, sometimes needlessly. On Friday he hurled another verbal wrecking ball into the conversation with U.S. allies, suggesting that Russia, which was tossed out of the Group of Eight after its annexation of Crimea, should be brought back into the club. The off-the-cuff comment drew rebukes from others in the G-7.

Some foreign policy experts believe Tuesday's summit would not be taking place were it not for the provocative approach Trump took early in his presidency toward the leader he derisively called "Little Rocket Man. Others suggest those tweets and threats about "fire and fury" were far less important than other factors beyond Trump's control that produced Tuesday's summit.

"That we've gone through this disruption phase is not a surprise, given his personality and why he was elected, and given that he is trying to set the table in a different way," said Stephen Hadley, who was national security adviser to President George W. Bush. "The question now is, can he do different kinds of deals?"

The Singapore summit will be an early test of his capacity - and willingness - to change.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author