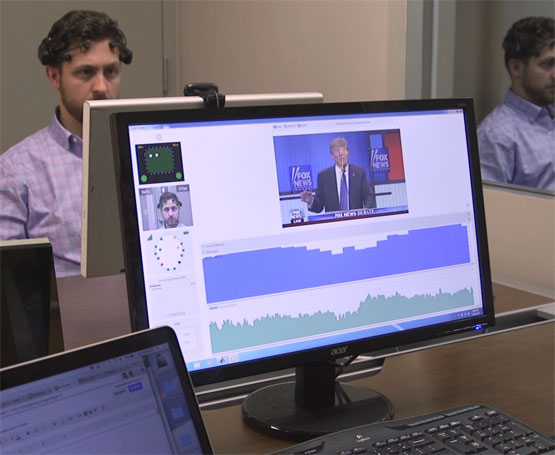

Neuroscientist Ryan McGarry swabbed a brain activity headset with saline solution and lowered it onto Brian Hazel's head, connecting circular prongs gingerly to different spots on his skull.

Then he showed Hazel 40 minutes of presidential debates and commercials as Spencer Gerrol tried to read his mind. Which of the candidates did Hazel, an African American real estate professional in his 40s, support?

Gerrol, founder and chief executive of creative agency Spark Experience, based in Bethesda, Md., stared through a one-way mirror from an observation room. "Trump," he said five minutes into Hazel's session.

Gerrol was right. "Donald Trump," Hazel said after his session. "I'm all about jobs, and if I look at the whole field and who has created the most jobs, I think he would be able to do that better than anyone else."

Spark's experiment is leading a new method of human factors research, which asks test subjects to interact normally with everyday products or services while researchers track their emotional reaction and attentiveness. The agency gathers data from four tests - electroencephalograms, galvanic skin responses, eye tracking and microfacial recognition - to instantaneously determine which candidate a subject supports, down to the severity of emotional response.

The firm gathered more than 30 test subjects from across the political spectrum in May. Their findings, released last week, show that what people feel and what they say they feel are rarely the same.

The experiment might be the closest the country gets to an explanation of this crazy presidential campaign without dissecting a brain.

Instead of placing participants in focus groups or asking them to fill out a questionnaire, experimenters harvest data directly from the brain using technology called "BrainWave." Companies such as Nielsen and Affectiva also conduct similar testing, which can gauge the effectiveness of advertisements and viewer response to TV shows and movies.

"This isn't science fiction," Gerrol said. "I can't read your thoughts, but I can read your emotions."

The firm used this same methodology to help gaming app "Angry Birds" capitalize on advertising techniques. Turns out, flashing an ad on the screen after a bird has just successfully slammed into a pig maintained users' attention three times as long, making Angry Birds players less angry.

But it has particular application this election cycle because voters' responses have been so unpredictable. Spark's study may have provided some answers, namely that test subjects may subconsciously lie when they tell people what political messaging works and what doesn't.

"If you ask somebody what they're feeling, you're not going to get a very accurate response. Emotion is subconscious," Gerrol said. "The idea is to measure emotion without asking.

"When people make decisions, it's tempting to think there's a lot of rational thought. That's not really true. You can't have decisions without emotion."

Trump supporters told researchers they didn't like their candidate's messages about wanting to ban Muslims from entering the country. But data show that participants found those messages resonated positively with Trump's base.

When candidates lobbed "baseless attacks," as they're wont to do, voters reacted negatively. Unless Trump hurled the insult. Then they laughed it off and moved on. They were even disappointed when Trump didn't use terms such as "Little Marco" or "Lyin' Ted."

Trump held voters' attention exceedingly well, at a 7 on a 10-point scale. That's better than even the most popular TV commercials. His references to the Islamic State and overseas trade wars stirred up fear, the most intense emotion humans experience.

Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton averaged a 4 out of 10. Voters were bored with her résumé, results show, which she repeats time and again.

Those are results that Gerrol says traditional polling methods won't capture because they ask subjects to interpret their own emotions, which inevitably get filtered.

Eight years ago, when CNN debuted a focus group-based emotional ticker during presidential debates, Gerrol set out to standardize and individualize how researchers measure emotional engagement.

Instead of asking participants to turn a dial when they feel good or support a certain message, Gerrol wanted to measure emotion using biometrics.

Politics, especially in the era of Trump, seemed like a natural extension for Spark. Gerrol called this election cycle "the combination of advertising and entertainment."

Scores of political prognosticators predicted Trump's demise almost a year ago. They predicted that Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders would fizzle out.

Alas, no political prediction has rung true, leaving political professionals and junkies alike asking, "What gives?" and "What are Trump and Clinton voters thinking?"

Spark's Brainwave study may have an answer: It's something about the way Trump and Sanders speak.

For some, Trump is fun to watch. His wild policy proposals, his crude language to describe his - err - hands and his goofy nicknames for his rivals endear him to supporters.

Participant Debbie Newton, of Kensington, Md., says she supports the real estate magnate because of his positions on immigration and spending. But she also says she hates his behavior. She calls him a "bully" and says he's not presidential "at all."

"As many [Republican candidates] as there were, it didn't feel like there was a good choice," she said. "The fact that it's come to Trump now is unbelievable."

But during the test when Trump launched into an attack on "Little Marco" Rubio, she exhibited strong positive emotion, data showed.

When Rubio said, "I would prefer to have a policy debate," instead of commenting on the size of Trump's hands, her attention dropped.

It rose again when Trump defended his hand size and "something else."

Hazel's attention measurements perked up during a Trump ad featuring Ivanka Trump, the candidate's daughter, and a Clinton ad narrated by Morgan Freeman. Afterward, he likened Trump's brashness to a football coach. He's very race-conscious, he said, but sometimes you have to dispense with niceties to get stuff done.

Then, he zoned out when The Donald jousted with narrators and opponents.

"Sir, that's the facts," Fox News Channel's Chris Wallace told Trump during a debate segment on health care. To Hazel, it barely registered.

"The entertainment value of politics is actually really important," Gerrol said in the observation room. "Really, all the debates are kind of like jokes. It's like a big circus."

But participant Tony Acquaviva of Silver Spring, Md., isn't amused. He says he's voting for "the lesser of two evils," Clinton. He says it's the first time he has voted out of fear.

But he also is incredibly detail oriented, results showed. He tuned out fights between the Democratic and GOP rivals, and his positive emotions and attention spiked when Clinton broke down her stance on minimum-wage increases.

"Watch this," Gerrol said, as a minute-long Clinton ad wound down.

"I'm Hillary Clinton, and I approve this message," the former secretary of state, senator and first lady said.

Acquaviva's emotions skyrocketed to a level researchers have classified as "joy."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author