Electability is an elusive concept. It is not one of those that fits into the category of, "I know it when I see it." It is born of individual biases and the conventions of history, often the search for something that seems to replicate something that was successful before. But a look back at presidential campaigns of the past suggests something else has been more powerful in determining who wins the White House.

Four years ago at this moment, almost no one, except perhaps the man himself, believed that Donald Trump was electable. He wasn't even a formal candidate, after all. Although he had been on the edge of the political stage, conventional wisdom afforded him little chance of becoming the 45th president. On the electability scale, he was in the low range.

Twelve years ago at this time, Hillary Clinton was judged to be the most-electable Democrat seeking the nomination. A New York senator, former first lady and part of the then-best brand in Democratic politics, she had the attributes that added up to being most electable.

Barack Obama, then a relatively new U.S. senator, was considered much more a long shot. As he said later, he believed he had about a 25 percent chance of winning the nomination - good enough to make the race but certainly no iron lock for someone whose race alone made him a long shot in the eyes of the conventional wisdom committee.

Four decades ago at this moment, Jimmy Carter was a little-known, one-term governor of Georgia, just starting to make his way around the country, carrying his own bag, sleeping in the homes of friendly Democrats. Who thought he was electable in a field of more than a dozen candidates, including several prominent senators with vastly more experience and recognition within their party?

Who thought, at this point in the 1980 campaign, that then-Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Mass., he of the dynastic family of Democratic politics, would crater in his effort to deny Carter the Democratic nomination? He might have looked electable, but events and his own deficiencies as a candidate did him in.

How many in those early days of the 1980 campaign truly thought Ronald Reagan could win the general election that year? The former governor of California had run for president twice before and lost both times. His views were seen as too conservative to win a general election. But he led a movement that brought him the nomination. In November, he won an electoral landslide and was re-elected four years later by a bigger margin.

What these successful candidates had was something other than the aura of electability. They had something that connected with voters more directly, more personally and more deeply. They stirred passions and in some cases anger. They excited. They inspired. They built followings. Obama's "Hope and Change," and Trump's "Make America Great, Again," were not based on the theme of electability. Quite the opposite. Obama's pre-campaign book was entitled "The Audacity of Hope" for a reason.

The best candidates tell a story, paint pictures, turn personal biography into something that connects them to the wider electorate. Experience can matter but it is not enough just to argue personal readiness to serve as president.

Successful candidates match a moment in the history of the country. For Carter, running two years after the resignation of Richard Nixon, it was the promise of something fresh, untainted by Washington, a message of integrity, rectitude, even righteousness, after the poison of the Watergate scandal.

Bill Clinton won in 1992 in part because other more prominent Democrats decided not to challenge George H.W. Bush, who was at about 90 percent in the polls in the spring of 1991. Early in the cycle, Clinton was hardly an obvious or likely winner. It was his New Democrat message, combined with the promise of generational change, that overcame his personal vulnerabilities eventually won over an electorate that was ready to move on after 12 years of Republican presidents. The most recent Washington Post-ABC News poll looked at two sides of the question of what Democrats and Democratic-leaning American are looking for in a nominee to challenge Trump in 2020. Do they want someone who agrees with them on issues or do they want someone who beat Trump? What is their priority?

Liberal Democrats narrowly prefer someone who can defeat Trump. Moderate and conservative Democrats want someone close to them on issues. Young voters want a candidate who agrees with them on issues. Older Democrats want someone who can beat Trump. White Democrats without college degrees want someone close to them on issues. White Democrats with college degrees prefer someone they think can win by a margin of 11 points.

That is one way to evaluate the mood of Democrats. Another question looked at how Democrats think about the best way to mobilize enough voters to win the general election. Specifically, the question asked whether it is more important to find a candidate who can energize the party's base or win over independent voters. Overall Democrats and those who lean Democratic were not far apart, though with a slight preference for someone who energizes the base.

However, nonwhite Democrats and leaners were significantly more likely than whites to say they prefer a candidate who energizes the base. That was also the case of women versus men. In the other direction, whites with college degrees titled more heavily toward a candidate who can win over independent voters.

The attitudes of nonwhite Democrats and Democratic women could reflect the fact that they want a candidate who pays attention to them and feel the nominating process already is unfairly skewing away from them.

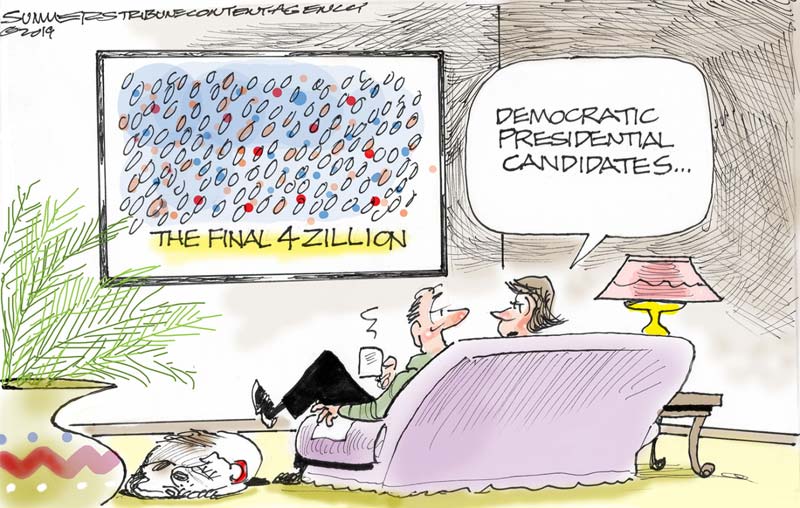

Already there are expressions of discontent that the attention currently being given to a few white, male Democratic candidates is out of proportion, given the qualities that the female candidates and candidates of color bring to the race.

Defeating Trump looms large in the minds of Democratic voters but past elections show that electability is not by any means the quality that elevates a candidate. Voters want something more - and they know it when they see it.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author