--- Russian television

![]()

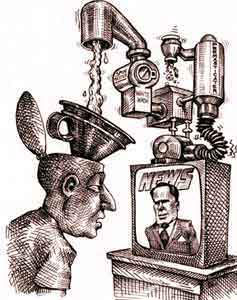

Because it touches us, because it involves the U.S. president, and because it has produced a lot of headlines, the strategy and tactics of Russian government disinformation in the West have lately been big news. Because it's far away, and because it happens in a different language, we've thought a lot less about Russian government propaganda in Russia. But it will eventually matter to us - maybe sooner than we think.

The transformation of Russian media hasn't happened overnight. Back in 2010, the Internet in Russia was a relatively vibrant place, where people with different kinds of ideas argued things out, at least some of the time. Independent media had some traction, and independent voices were heard. There were negative stories about the Western world, but positive ones, too. Eight years later - following Vladimir Putin's return to the presidency, and a sharp change in government information policy - the situation is different.

This isn't because Russia has become the Soviet Union, or a totalitarian state with one newspaper. Russia now has multiple sources of information: different television channels, many with high-quality entertainment programs; a range of newspapers, some very professional; both highbrow and lowbrow magazines and websites. But the appearance of variety is deceptive. Though the styles are very different, the vast majority of media is owned by the state or state-linked companies, and the stories are often remarkably alike. On television, which is where most Russians get their news, much of what they see about the West is overwhelmingly dark and negative.

Arecent survey of the three main Russian television channels produced some stark analysis of what Russians are hearing about Europe. Researchers examined newscasts and political talk shows from summer 2014 to December 2017. They found that negative news about Europe appeared on the three channels an average 18 times per day. The percentage of negative to positive news about European countries is 85 percent to 15 percent; for some European countries the ratio is even more skewed. France - perhaps because its most recent presidential election featured Marine Le Pen, a clearly pro-Russian candidate who lost to a pro-European one - was depicted negatively most often.

Most of the stories, ranging from big news events to local murders to sheer inventions ("the German government is taking children away from their families and giving them to gay couples") fit into a particular set of narratives. Daily life in Europe is depicted as frightening and chaotic; Europeans are weak, with declining morality and no common values; terrorism keeps people paralyzed with fear; the refugee crisis is getting worse all the time; sanctions on Russia have backfired and are now undermining the European economy and destroying the welfare state. Russia, in the version of the world depicted here, does not need a welfare state, since its citizens are so much hardier.

This research echoes earlier studies, such as one from last year, that also noted how often the European Union is shown by Russian media as aggressive and interventionist, alternately planning to use Ukraine as a dumping ground for nuclear waste, or merely forcing its members to adopt "Russophobic" policies.

The uses of this kind of coverage aren't hard to guess. Clearly, it is not in the Russian state's interest for the Russian nation to admire Europe, not for its democracy or its rule of law, and certainly not for its high standards of living. The memory of the Maidan protest of 2014 - young Ukrainians protesting in Kiev, waving European flags and calling for an end to corruption - is still fresh enough to be frightening in Moscow. If the Putin regime can undermine the idea of "Europe" and make it unattractive to Russians - most of whom have long identified themselves as Europeans - then it removes a source of hope, and a possible model. If Europe is crazy, twisted, dangerous and dying, then surely Russians are better off under their corrupt authoritarian system.

There could be a more sinister purpose to this relentless bad news as well, particularly as it echoes equally harsh coverage of the United States and Ukraine. If Russia were expecting or planning some kind of conflict with Europe - diplomatic, economic, political, even military - this is exactly the strategy Russian leaders would use: Portray Russia's neighbors as simultaneously aggressive and weak, decadent and dangerous; show Europe as a society that a stronger, better Russia could - and should - easily crush. Perhaps this is overly pessimistic.

But otherwise it's hard to explain why Moscow would go to the trouble.

Anne Applebaum is a Washington Post columnist.She is also the Director of the Global Transitions Program at the Legatum Institute in London.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author