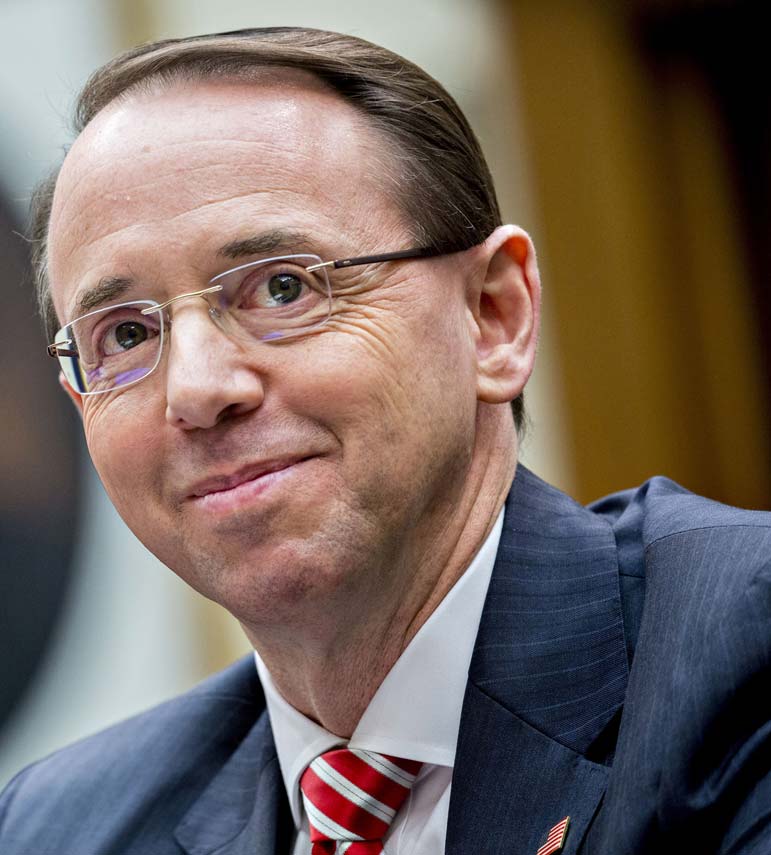

Andrew Harrer for Bloomberg

Andrew Harrer for Bloomberg

On a mahogany table, he set down several binders filled with briefs, along with a cardboard folder that had belonged to his father. Rosenstein then walked over to greet some fellow prosecutors who had come early for front-row seats so they could - silently - cheer him on. Holding out his arm, Rosenstein proudly showed them his new "Donald Trump cuff links," which the White House counsel had sent to his office for him to wear.

"Not bad," he said, smiling, moments before his first Supreme Court appearance began.

In recent weeks, it was unclear whether Rosenstein's big day was going to happen. The Justice Department's second-highest-ranking official has been in President Trump's sights for months.

Two weeks ago, Trump, angered by the ongoing Russia investigation and Rosenstein's approval of the FBI's raid of his personal attorney's office, told senior officials that he was considering firing the deputy attorney general. Attorney General Jeff Sessions recently indicated to White House counsel Donald McGahn that he might have to step down himself if Trump fires Rosenstein, whom he chose as his deputy.

But Monday, Rosenstein walked to the lectern to face eight of the court's justices at their raised bench in front of four marble columns and two American flags. (Justice Neil Gorsuch did not take part in the argument, probably because he had some contact with the case when he was on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit.)

Rosenstein's Supreme Court appearance is not unprecedented; while attorneys in the solicitor general's office usually argue cases for the government, other deputy attorneys general, including one James Comey, have appeared before the court.

"General Rosenstein," Chief Justice John Roberts said, looking down at the deputy attorney general.

"Thank you, Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the court," said Rosenstein, who appeared polished and confident, a reflection of his nearly 30 years as a federal prosecutor.

Chavez-Meza v. United States, No. 17-5639, is a low-profile case from New Mexico involving the prison sentence of a convicted drug dealer. But the chamber was packed because Rosenstein was in court defending the administration.

At issue was how much a federal court judge is required to explain when ordering a partially reduced sentence for a defendant after the sentencing range for the crime has been lowered by the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

In 2012, Adaucto Chavez-Meza, 19, and two others were arrested in Albuquerque in a sting operation when they tried to sell about four pounds of methamphetamine to an undercover agent. In 2013, Chavez-Meza pleaded guilty to conspiracy and possession with intent to distribute methamphetamine. He was sentenced to 11 years and three months in prison, which was the minimum amount under the federal sentencing guidelines.

A year later, the Sentencing Commission changed its drug-offense guidelines, which lowered the sentencing range for Chavez-Meza's type of crime. The defendant asked the court to lower his sentence. The judge did reduce his sentence by 21 months. But under the new guideline range, the new minimum sentence would have been a reduction of 27 months.

The judge did not explain his decision, and Chavez-Meza argued that he should have. Federal courts split on the degree of explanation required of the judge.

"There must be a reason for the district court's decision apparent in the record," attorney Todd Coberly said, arguing for Chavez-Meza. Coberly said he was asking for the federal court to come to "a reasoned decision as to why it's imposing a particular reduced sentence."

Rosenstein argued that no such explanation from the judge was necessary. The federal appeals courts should "presume that district courts know the law and apply it faithfully," he said.

"What the district court did here is more than sufficient," Rosenstein said. "The court made clear on the record that it had considered the relevant factors. . . . The court was familiar with the case by virtue of having handled the original sentencing and imposed a sentence that is reasonable and for that reason should be upheld."

Several justices, including Justice Elena Kagan, raised questions indicating it might be helpful for judges to state their reasoning in sentencing cases.

"Do you think a judge can terminate a period of supervised release and send somebody back to prison without any statement of reasons?" Kagan asked.

When the one-hour argument was over, Rosenstein walked outside with his wife and two teen daughters. At the top of the white steps of the Supreme Court building, he posed for a photograph with his family. He walked over and shook hands with Coberly, who was standing with his wife and little girl.

"He congratulated me and said 'Great job,' " Coberly said. "It was a great experience to argue against such a great advocate. I think he did the best he could with this case."

When asked by a reporter how he thought his argument went, Rosenstein simply smiled. He stepped into an SUV with his family and was whisked away.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author