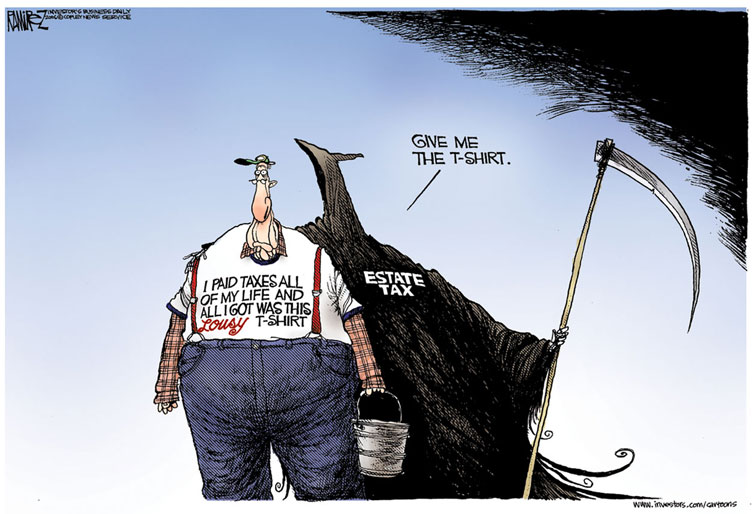

Prepare for the rise of the landed nobility. Democracy as we've known it was nice while it lasted, but House Republicans have signaled the beginning of its end with a vote to repeal the estate tax.

Or so you would believe, based on the hysterics on the left over the proposed end of a minor, inefficient tax that is evidently the fragile keystone of our system of government and way of life.

"Repealing the estate tax will surely sow the seeds of a permanent aristocracy in this country," according to Rep. Jim McDermott of Washington. His colleague, Rep. Ron Kind of Wisconsin, denounced the rise of "a caste system where birth equals outcome."

The unhinged reaction to the House vote -- the Senate won't pass repeal, and President Barack Obama would veto it if it got to his desk -- is based on the Democrats' profound worry that someone, somewhere, might be passing on wealth to his or her heirs.

That they consider this a bizarre, threatening act that should be restrained as much as possible by the force of government speaks to their disconnection from human nature, not to say basic justice.

From time immemorial people have sought to better their lot in life, in part to provide for their children and grandchildren. By any reasonable standard, this is a praiseworthy and unselfish motivation. In what perverse world is it a criticism to say of someone at his death, "It's such a shame -- he saved too much money to pass on to his kids and their families"?

Democrats look at such an elemental human act and see, firstly, a dastardly blow for wealth inequality (because not everyone is blessed with such parents and grandparents), and, secondly, a taxable event. The estate tax is the vehicle for these impulses.

At 40 percent, the U.S. has the fourth-highest marginal tax rate on estates of any developed country. But the exemption is high, $5,430,000, to keep the tax from ensnaring families who aren't plutocrats, but have built successful businesses and farms.

This means the revenue haul is relatively insignificant, at $20 billion a year, although the compliance costs are high. (The wealthiest of the wealthy deploy a battery of tax specialists and lawyers to shield their assets from taxation, regardless.)

Other countries have concluded that the estate tax simply isn't a good way to raise revenue. Some Scandinavian social democracies manage to do without estate and inheritance taxes, but we're supposed to believe the good ol' USA will be utterly bereft without one. (Both Sweden and Norway eliminated theirs in recent years.)

The utility of the estate tax is really as a symbolic totem of the redistribution of assets that the left considers ill-gotten gains.

Dana Milbank, whose column appears on JWR for "balance", Washington Post huffs that reducing the bite of the estate tax, "does little to prevent a permanent aristocracy from growing -- and abolishing it entirely turns democracy into kleptocracy." A kleptocracy? That is the corrupt rule of a self-serving elite. In this case, the alleged corruption consists of families keeping their own wealth within the family.

Sen. Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., has said that repealing the death tax means "helping the wealthiest people in the country." Helping. Is it really such untoward assistance to allow you to control to whom your wealth goes upon your death?

Most Americans would answer "no," which is why the estate tax is persistently unpopular even though its reach is relatively small. Liberals tend to be puzzled by public opinion on this question. "Like it or not," blogger Kevin Drum has written by way of explanation, "I think that most people simply have an instinctive feeling that you should be able to bequeath your money to whoever you want."

Of course they do. It takes a peculiar ideology indeed to think the opposite and to consider someone's death as an occasion to strike a blow for social justice

Comment by clicking here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author