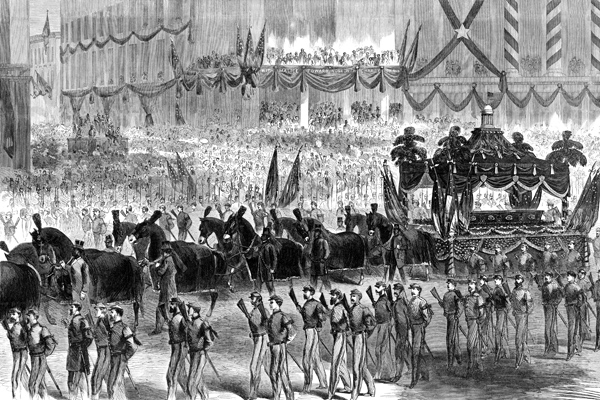

President Lincoln's funeral procession in New York City.

President Lincoln's funeral procession in New York City.

As America marks the 150th anniversary of Lincoln's death today, fresh insight into the events that occurred a century and a half ago can be gleaned by seeing that entire week through the eyes of America's Jews, and especially of those Jews who attended America's oldest and most historically distinguished congregation.

On Sunday, April 9, 1865, Generals Grant and Lee met in Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia. Lee surrendered, and the Civil War came to an end, with 360,000 Union and 260,000 Confederate soldiers dead. The news broke all over the United States on April 10, which, in the Hebrew calendar, was the morning before the eight-day holiday of Passover was to begin. We can imagine the elegant symmetry that those Jews sympathetic to the Union cause saw in the advent of their Festival of Freedom, commemorating the Israelite exodus from slavery, coinciding with the Confederacy's defeat. Thinking of their own relatives, who like other Americans had fought, bled, and died for several terrible years, we can imagine their finding a double meaning at their Seder tables that Monday evening, as they uttered the immortal words of the Haggadah: "Why is this night different from all other nights?"

It was four days later, on Friday evening, when the president ventured out into a joyful, festive Washington for an evening at Ford's Theatre, that he was shot. Carried to a boarding house across the street, Lincoln died at 7:22 a.m. on Saturday. It is often told that all those crowded around his deathbed turned to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who said simply, "Now he belongs to the ages." As the writer Adam Gopnik has noted, these words are the best-known epitaph in American history, and probably the finest: "They seem perfectly chosen, in their bare and stoical evocation of a Lincoln who belongs to history alone, their invocation not of an assumption to an afterlife but of a long reign in the corridors of time, a man now part of eternity."

Conveyed by telegraph, the news soon reached the rest of the country. Jews heard it from their fellow Americans on the day of the celebratory service held on the Sabbath during Passover. Bertram Korn, in his American Jewry and the Civil War, describes the scene:

Jews were on their way to synagogue or already worshipping when tidings of the assassination reached them. .??.??. Jews who had not planned on attending services hastened to join their brethren in the sanctuaries where they could find comfort in the hour of grief. The Rabbis put their sermon notes aside and spoke extemporaneously, haltingly, reaching out for the words to express their deep sorrow. .??.??. Samuel Adler of Temple Emmanuel in New York began to deliver a sermon but he was so overcome that he could not continue. Alfred T. Jones, Parnas of Beth El-emeth Congregation of Philadelphia, asked [the well-known Jewish scholar and writer] Isaac Leeser to say something to comfort the worshippers; he did, but it was so disconnected that he had to apologize: "the dreadful news and its suddenness have in a great measure overcome my usual composure, and my thoughts refuse to arrange themselves in their wonted order."

Because the president died on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, the first utterances from the pulpit in response to the assassination were heard in synagogues, as Isaac Marken explains in Abraham Lincoln and the Jews. One of the most striking—and indeed, controversial—moments took place in Congregation Shearith Israel, in New York, the oldest Jewish congregation in America. There, Marken recounts, "the rabbi recited the Hashkabah (prayer for the dead) for Lincoln. This, according to the Jewish Messenger, was the first time that this prayer had been said in a Jewish house of worship for any other than those professing the Jewish religion." This seeming deviation from tradition in Shearith Israel—known to this day for its fierce devotion to preserving religious and liturgical tradition—was noted by many, and defended by the aforementioned Isaac Leeser, who also edited American Jewry's most prominent newspaper:

It is, indeed, somewhat unusual to pray for one not of our faith, but by no means in opposition to its spirit, and therefore not inadmissible. We pray for the dead, because we believe that the souls of the departed as well as of the living are in the keeping of G0D. .??.??. The prayers, therefore, offered up this day for the deceased President are in accord-ance with the spirit of the faith which we have inherited as children of Israel, who recognize in all men those created like them in the image of G0D, and all entitled to His mercy, grace and pardon, though they have not yet learned to worship and adore Him as we do who have been especially selected as the bearers of His law.

The prayer for Lincoln, in other words—one of the first religious reactions to Lincoln's death—embodied the belief in human equality that lay at the heart of Lincoln's worldview: that this was a nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the idea that all men are created equal. At the same time, the reciting of the prayer—which asks on behalf of the deceased for a "goodly portion in the life of the World to Come"—also embodied the belief the members of Congregation Shearith Israel had in Lincoln's spiritual immortality. A focus on spiritual immortality may have been Stanton's original intent as well; because, as Gopnik himself has noted, as perfect as our version of Stanton's epitaph may seem to us today, it very possibly is not quite accurate. The closest source we have to an eyewitness is a Corporal Tanner, a soldier, who took dictation from Stanton. Tanner described the final moments of Lincoln's life in his own words:

The Reverend Dr. Gurley stepped forward and lifting his hands began "Our Father and our G0D" and I snatched pencil and notebook from my pocket, but my haste defeated my purpose. My pencil point (I had but one) caught in my coat and broke, and the world lost the prayer, a prayer that was only interrupted by the sobs of Stanton as he buried his face in the bedclothes. As "Thy will be done, Amen" in subdued and tremulous tones floated through the little chamber, Mr. Stanton raised his head, the tears streaming down his face. A more agonized expression I never saw on a human countenance as he sobbed out the words: "He belongs to the angels now."

Stanton's original reference, then, may have been to Lincoln's place amongst the angels, not the ages. The question of what Stanton actually said, Gopnik notes, "leads to the most vexed question in all the Lincoln literature, that of his faith. How religious—how willing to credit more than metaphoric angels—did the men in the room think that Lincoln was?" After all, as anticlerical as Lincoln may have been in his youth, there is no question that his most famous speeches are laced with biblical references, and he began to see the work of Divine Providence in the history of the United States and the elimination of slavery from a nation conceived in liberty. "The Second Inaugural," Gopnik notes, "is the most famous instance, with its insistence that 'if G0D wills that [the war] continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."?'?" It was this Lincoln about whom Stanton likely said, "Now he belongs to the angels"; and if he did not say it, then perhaps the first ones to say it were the members of Congregation Shearith Israel.

As terrible as it was, Lincoln's death on Passover, and the Jews' joining their observance of this holiday with their mourning of his death, is curiously fitting. For as Britain's former chief rabbi, Jonathan Sacks, notes in his commentary on the Haggadah,

In a strange way civil religion has the same relationship to the United states as Pesach [Passover] does to the Jewish people.

It is first and foremost not a philosophy but a story. It tells of how a persecuted group escaped from the old world and made a hazardous journey to an unknown land, there to construct a new society, in Abraham Lincoln's famous words, "conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal." Like the Pesach story, it must be told repeatedly, as it is in every inaugural address. It defines the nation, not merely in terms of its past but also as a moral, spiritual commitment to the future. It is no accident that the founders of America turned to the Hebrew Bible, or that successive presidents have done likewise, because there is no other text in Western literature that draws [on] these themes. .??.??. Israel, ancient and modern, and the United States are the two supreme examples of societies constructed in conscious pursuit of an idea.

The Passover story, in other words, has always been linked to that of America. Indeed, Benjamin Franklin first suggested that the seal of the United States depict Pharaoh drowning at the Red Sea, with the motto "Rebellion to Tyrants Is Obedience to G0D." Matthew Holbreich, a scholar at Yeshiva University's Straus Center, and Yale's Danilo Petranovich, note in a coauthored article that even before the Civil War, Lincoln drew on the same biblical imagery to predict the possibility of divine punishment for slavery; in his eulogy for Henry Clay in 1852, Lincoln reflected that "Pharaoh's country was cursed with plagues, and his hosts were drowned in the Red Sea for striving to retain a captive people, who already served them more than four hundred years. May like disasters never befall us!" The eternal link between Lincoln's life and Passover—the fact that Lincoln's death, marked in the Hebrew calendar, coincides with Passover every year—is certainly fitting, and perhaps even part of the providence that Lincoln began to see in his own life, and the life of his nation.

With this in mind, we are now able to glean one more fascinating link between Lincoln's life and death and the Passover holiday. In his famous "House Divided" speech, delivered on June 16, 1858, when he accepted the nomination of the Republican party for a seat in the U.S. Senate, Lincoln reflected on the new political party that had been born to fight slavery:

Two years ago the Republicans of the nation mustered over thirteen hundred thousand strong. We did this under the single impulse of resistance to a common danger, with every external circumstance against us. Of strange, discordant, and even hostile elements, we gathered from the four winds, and formed and fought the battle through, under the constant hot fire of a disciplined, proud, and pampered enemy. Did we brave all then to falter now?—now—when that same enemy is wavering, dissevered, and belligerent? The result is not doubtful. We shall not fail—if we stand firm, we shall not fail [italics in the original].

As Holbreich and Petranovich have noted, Lincoln's phrase "gathered from the four winds" is biblical, a reference to the story in Ezekiel where the prophet sees a field full of dry bones, a symbol of Israel's loss of hope following exile. As the bones come together to form bodies, Ezekiel is told:

"Prophesy to the spirit, prophesy, O son of man, and say to the spirit, 'So says the Lord G0D: From four winds come, O spirit, and breathe into these slain ones that they may live.'?"

And I prophesied as He had commanded me, and the spirit came into them, and they lived and stood on their feet, a very great army, exceedingly so.

In invoking this image, Holbreich and Petranovich write, "Lincoln envisioned the eradication of slavery in terms of a moral resurrection."

Here, however, is what no scholar has noted before: The story of the Valley of the Dry Bones from the Book of Ezekiel is read in synagogues all over the world when the Sabbath takes place in the middle of Passover, as it did the year Lincoln died. The tale in Ezekiel is read on Passover because the holiday itself commemorates, for Jews, our moment of national resurrection, our new birth of freedom. The prophetic portion is read immediately after the reading from the Torah and the recitation of memorial prayers, so at Congregation Shearith Israel in 1865, it would have almost immediately followed the memorial prayer for Lincoln.

We are now able to reconstruct what happened in Shearith Israel that day. The news of the assassination broke as services were beginning. The rejoicing over the Passover holiday and the Northern victory were all of a sudden turned to mourning. A traditional Jewish prayer was recited for the soul of a Gentile, the Gentile who embodied for these Jews the best of humanity. By saying the prayer on his behalf, Jews expressed their faith both in his spiritual immortality and in the posterity of his principles; they were, one might say, stressing that he belonged both to the ages and to the angels. These Jews then read the first half of Ezekiel's 37th chapter, the story of the Valley of the Dry Bones, a tale embodying a new birth of freedom, at the moment that the civil war came to an end. Holbreich and Petranovich reflect that Lincoln, in referencing Ezekiel's Valley of the Dry Bones in his "House Divided" speech, surely knew that chapter's final verses. The prophet concludes by referencing ancient Israel, which had been split into a northern and southern kingdom; and one can conceive of no more fitting verse with which to capture Lincoln's legacy:

And I will make them into one nation in the land upon the mountains of Israel, and one king shall be to them all as a king; and they shall no longer be two nations, neither shall they be divided into two kingdoms anymore.

This Passover marks the 150th anniversary of Lincoln's death, 150 years since the end of the Civil War, 150 years since American Jews first said a prayer for the soul of a non-Jew, a man named Abraham. Seeing these events through those Jews' eyes helps this profound moment of our history to remain fresh in our own eyes and invites us to dedicate ourselves with renewed vigor to the principles for which Lincoln stood, and for which he died, that they shall not soon perish from the earth.

Comment by clicking here.

Meir Y. Soloveichik is the rabbi of Congregation Shearith Israel in New York and director of the Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought at Yeshiva University. This article first appeared in The Weekly Standard.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author