Almost half the fatalities were people between 20 and 40 years old - the very adults relied on as parents, breadwinners and leaders. Desperate to control the pandemic, public health officials prohibited public gatherings and closed schools, churches and other institutions. They even placed restrictions on funerals. Many communities prohibited anyone other than adult members of the immediate family to attend, and the bodies of the deceased were routinely barred from being taken into churches or chapels.

When the pandemic subsided, people rushed to regain their sense of equilibrium and normalcy: While Americans had proved remarkably compliant with health officials' initial demands, they were reluctant to keep those restrictions on their lives - even as many communities faced a subsequent wave of the illness.

Certain habits did change. Americans never returned to the common drinking cup, outlawed during the crisis and previously common in schools, offices and railway cars; they frowned on public spitting. Public health leaders celebrated their success in providing basic education on sanitation and personal hygiene. But the deaths of 675,000 Americans did not spur a remaking of the health-care system. Efforts by Progressive-era reformers had failed to create a national health insurance program and, despite the pandemic, withered in the 1920s.

As influenza ransacked their communities, many Americans clung to the familiar, adhering to established ways of doing things. Men and women faced pressure to respond to the pandemic according to gendered norms.

In letters and diaries from the time, women openly discussed their fears and their experiences of loss; because they were assumed to be innately self-sacrificing and skilled at caregiving, women were called upon to be nurses.

Men, meanwhile, were expected to exhibit only strength and stoicism; they expressed guilt and shame when illness required them to take to their beds. People of color continued to face segregated health care: Philadelphia opened emergency clinics for white residents but did nothing for its African American community. Eventually, a local black physician organized their care.

In Richmond, Virginia, African American patients could visit the new emergency hospital, but they were relegated to the basement until the staff secured another, separate space for their treatment.

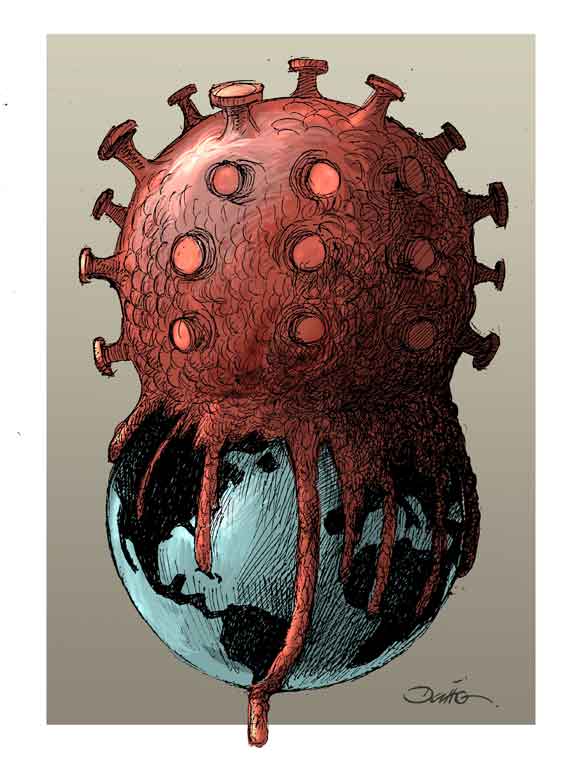

The pandemic did not disturb the social and economic inequities it had made visible. And yet, while knowledge of the past is essential to understanding the present, history is rarely a reliable predictor of the future. We need not repeat the mistakes of those who came before. Here are some ways our culture might change.

• The Touring Life, by Roseanne Cash, Grammy award-winning singer and songwriter

I put an end to the after-show meet-and-greets on the last tour, in early March, when things started to get serious. It hit me after the first performance, as friends of friends all came backstage together and squeezed me into the middle of a squirmy little clique for 10 minutes of photos. Three weeks later, I'm still thinking, "If I get sick, I'll know who to blame," although surely that window has closed. I finished the tour on March 14 with nary a handshake or hug. Issues that had never been issues began to crystallize. My tour manager started obsessively wiping down my microphones with alcohol: before sound check, after sound check, before the show, after the show. No more salad bars for lunch, ever (particularly any like the one at the Southern casino several years ago that considered M&Ms a fruit).

As for signing albums and pictures and odd things people bring to me after shows, that tour manager keeps a platoon of Sharpies in his jacket pocket so I don't have to borrow anyone's pen. It feels selfish to stop autographing things altogether. I've always thought that if someone uses their discretionary income to buy something I made, and they ask me to sign it, it is the gracious thing to do, but alcohol-wiping album covers is not a bad idea.

One venue put a sign on my dressing room door warning everyone but the cleaning crew to stay out, which was reassuring. I started looking at the open bowls of nuts and chips and guacamole in the green room as if they were petri dishes of proto-virus. After this is over, I will totally rewrite the tour rider to ban open bowls of food.

All those things seem like the granular view of the overprivileged. I freely admit I have that, and I am that. But I'm also on the board of the Artist Rights Alliance, which is focused on the dire circumstances many middle-income and already struggling musicians find themselves in, thanks to canceled tours, festivals and recording sessions, as well as shuttered music classes, where many musicians supplement their income by teaching. If the federal government offers assistance, we hope musicians and performers will be included.

I can't help thinking there is a Darwinian reset taking place, but it remains to be seen what evolutionary advantage is paramount - a sense of community and compassion, I hope. Performers become screens on which people project their needs, and perhaps the reflection we offer can be more "us" and less "me."

At the same time, I'll envision a future on the road minus photo bombs and green room petri-snacks.

• More Political Melodrama, by Liz Mair, founder, owner and president of Mair Strategies

Between 2008 - when I built the Republican National Committee's online communications division - and today, technology has become an increasingly important part of campaigns. In a post-pandemic America, those that invest in and adapt to communication-focused technology will succeed; those that can't, or won't, will fail.

The more local the race, the truer this is likely to be. In a presidential campaign, candidates can count on a certain amount of automatic media coverage, even if debates and town halls are canceled because of a need for social distancing. But if you're an unknown politician challenging, say, a sitting member of Congress, you'll have to generate coverage, voter enthusiasm and money on your own, probably without media outlets that could not care less about you. Social distancing would mean you couldn't just show up at a local church or county fair to press the flesh. Fundraising in swank mansions would be replaced by video conference calls with high-dollar donors. (The good news: no more inane "wine cave" attacks.)

More TV interviews will happen via Skype. More radio interviews will be over the phone, not in studio. Campaigns that master technology will give themselves a boost. The "end" will remain the same - getting more votes than your opponent. But the means will look very different.

That bad news is that, to make a name for themselves without meeting voters, candidates will have to be as interesting (read: outlandish) as possible. It might already feel like we occupy a land of 1,000 Donald Trumps, but get ready to actually live there. Nice-but-boring politicians can make it in retail politics, but they'll be a tougher sell in an online-dominated political environment. The catchiest tweets, not the soundest ideas or the most amiable personalities, will often win the day. Those of us who want less shtick and more gravitas from our leaders will have to adjust. Incentives will increase for everyone to turn into Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or Republican Rep. Joe Wilson. If a coronavirus vaccine doesn't arrive soon, politics, especially handcuffed to the internet, will be more melodramatic than ever.

• FaceTime With Your Doctor, by Kimberly Gudzune and Heather Sateia. Gudzune is an associate professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and clinical director of the school's preventive medicine residency; Sateia is an associate professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and assistant clinical director of the general internal medicine practice at Green Spring Station.

To reduce the risk of transmitting the coronavirus, health systems are hustling to switch to telemedicine. At our own institution, Johns Hopkins, and elsewhere, it's happening almost overnight: Technological platforms have been launched, providers trained, patients educated and appointments converted to video visits. Patients get to speak to their physician in real time, securely, from their smartphone or home computer.

You can't accomplish everything through this method - patients who need testing must still go to a lab, and you'll have to visit the doctor if she decides you need a physical exam. But it's an extraordinarily useful tool: Long after the pandemic subsides, its adoption could mean good things for the delivery of health care.

Research has documented inequities in accessing care by race, gender, weight, income and geographic location, among other factors. Telemedicine, which makes the connection between people and caregivers more frictionless, isn't a cure-all for such problems, but it can ameliorate them, and it's long been underused. One reason, in addition to the lack of tech platforms and training, is that health insurers have declined to cover "virtual" doctor's appointments. But they're doing so now, and we expect they'll continue.

Traditionalist doctors have also been nudged toward trying an unfamiliar model of care by this shock to the health-care system. Long term, the telemedicine revolution could reshape how we help patients manage chronic disease and practice preventive care, by making it far easier to stay in touch. The shift could also make it less difficult for doctors to reach patients in remote areas.

The pandemic may change medicine in other ways, too. Patients have been sharing with us their profound anxieties - and doctors, nurses and others are returning to the roots of the profession by recognizing anew how important it is to listen to, and empathize with, such concerns. Medicine is a clinical enterprise, but it also requires compassion that can be lost amid a focus on the latest treatments. The coronavirus has heightened the concern, too, about burnout among physicians and staff on the front lines of health care.

It's tough to comfort an exhausted, crying physician when you shouldn't touch each other, because of social distancing, but thousands of physicians are finding ways to connect and share our experiences - whether on social media, through first-person accounts on physician-focused podcasts, or other means. After the pandemic, keeping this spirit of collaboration and connection alive, and drawing on technology to achieve this goal, will produce a better health care experience for everyone.

• Not-So-Mass Transit, by Joel Kotkin, a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University and executive director of the Urban Reform Institute

Pandemics have always been the enemy of dense, urban life. Cities, where people live in close quarters and mix with people from other places, are ideal breeding grounds for contagions. So far, by contrast, there have been comparatively few coronavirus infections in the vast middle of the United States, particularly in the rural reaches. When the bubonic plague devastated Europe, as the historian William McNeill noted, the cosmopolitan centers of Renaissance Italy fared far worse than the reaches of Poland or other parts of Central Europe. Those grandees who could, like some contemporary wealthy New Yorkers, fled to their country homes, where the chance of infection was slighter.

Even before covid-19 hit, large urban centers like New York, Los Angeles and Chicago were losing population; more than 90 percent of all population growth since 2010 has taken place in the suburbs or exurbs. Millennials, as a new study from Heartland Forward demonstrates, based on an analysis of census numbers, increasingly head to cities and towns in the middle of the country and away from the supposed "magnets" of New York, Los Angeles and Chicago.

The current pestilence is likely to accelerate those shifts, which bear major ramifications for how Americans get to work. Transit ridership was doing poorly before the crisis, declining throughout the country, while telecommuting and driving alone continue to grow. With the specter of contagion, city-dwellers are told to avoid crowded subways, removing a critical element that makes ultradense cities work. In New York, subway traffic is down precipitously, as many commuters now work at home instead. Toronto is eliminating much of its downtown train service. The Washington Metro is also cutting back.

Just as progressives and environmentalists hoped the era of automotive dominance and suburban sprawl was coming to end, a globalized world that spreads pandemics quickly will push workers back into their cars and out to the hinterlands.

• Personal Greetings, by John Scalzi, a novelist

Two weeks ago, I was on a cruise - I know, I know, but look, no one officially said, "Hey, maybe don't go on a cruise" until the day after we left. But we all had a clear enough sense of what we were in for that one of the hot topics of discussion onboard was how the 2,000 of us were going to greet one another. Shaking hands was obviously not a great idea, much less hugging, either in its "full body" or "awkward side hug" variants. We had all just gotten onto a cruise ship; we wanted to be able to walk off it in a week's time and not be quarantined in our berths.

Many options were considered. This was the JoCo Cruise - a themed cruise with nerdy entertainers and passengers - so some folks tried to get the Vulcan and Wakanda salutes going. Others tried the "toe tap" maneuver, but that was quickly abandoned because it assumes you're on stable ground. Fist bumps were just hipster handshakes: You're still connecting with a part of someone's body that's been busily touching their face. Bowing seemed rather too formal for geeks in dark, sarcastic T-shirts.

Within a day, a winner emerged, one that was already under discussion on terra firma but that has rarely been attempted by any of the landlubbers I know: the elbow bump, in which two people thrust forward their elbows and touch them briefly together. It satisfied the convention of some physical contact, but with a body part that's so isolated it's unlikely to come into proximity to bacterial danger zones. (Go ahead, try to touch your face with your actual elbow, not just its crook. I'll wait.)

Off the ship - and we all did get off the ship just fine, thank you - I don't expect the elbow bump to gain much steam. I do think people will search for ways to greet each other if handshakes are considered bad form. Maybe it's the science fiction novelist in me speaking, but we could do worse than the Vulcan salute.

In the end, though, I suspect a simple wave "hello" will do the trick: an acknowledgment and a sign of potential friendship and an understanding that sometimes a little distance is kind, not rude.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Bristow, chair of the history department at the University of Puget Sound, and author of "American Pandemic: Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author