"I did!" someone will exclaim, offering a detail about that unfortunate person, like gender or a name. The psychic picks it up: "Yes, I saw a young girl who was reaching out to me," etc. Then another vague suggestion about a common object - Something about a window? - and the client does the rest of the work: Wow, we were once in a school play called "Windows"! How on Earth could the psychic have known that?

Humans are pattern-seekers, and psychics are good at leveraging this. When we're looking for connections between disparate things, we're good at finding them. Psychics simply sketch out a number of possible connecting lines and then take credit for the one the clients choose. One point of the movie "A Beautiful Mind" is that the ability to find or the insistence on finding connections between unrelated things can veer between insight and madness.

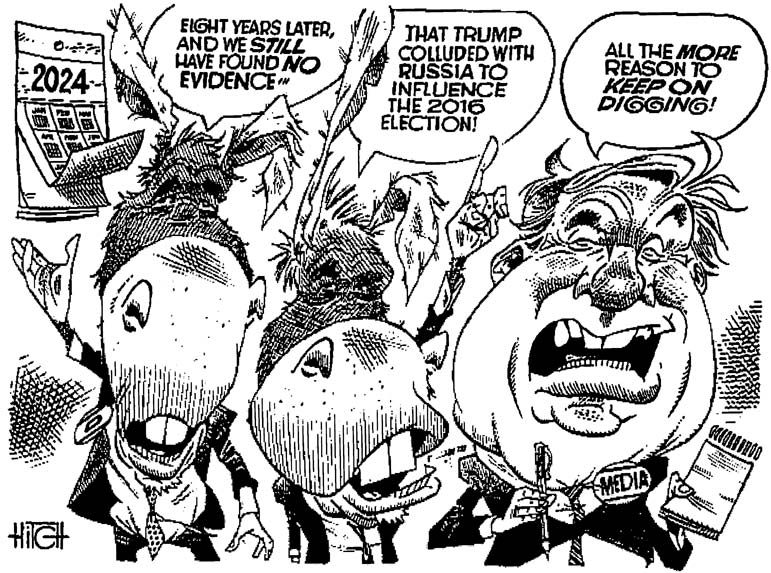

So let's talk about the Russia investigation.

When we hear about efforts by Russian actors to interfere in U.S. elections, interference that prompted a counterintelligence investigation by the FBI, it's natural that our minds jump to "Homeland"-style conspiracies.

Regardless of age, Americans grew up with a tangible sense of Russian spycraft thanks to pop culture, be it James Bond or "The Americans." We see the word "Russians" and start building out a thread-covered wall in our minds, linking this to that and seeking out new items to fit into our pattern.

So along comes Cambridge Analytica, a nefarious-sounding organization with an intriguing backstory and enough sketchy characters orbiting it to make any "Law and Order" screenwriter drool. We start with SCL Group, a company that is involved in advising governments, militaries and political campaigns around the world in sometimes eyebrow-raising ways. Its value proposition was that it could overlay psychological insights onto traditional marketing efforts.

A few years ago, conservative donor Robert Mercer funded the creation of Cambridge Analytica, a U.S.-based firm to bring SCL Group's techniques here. This is what led to the recent news about the firm misappropriating data from Facebook. Eager to build out psychological profiles of Americans after entering this market, Cambridge paid a researcher at a British University for data pulled from Facebook in what the social-media company says was a violation of its terms of use. That was combined with surveys conducted among Americans to test political messages.

In 2016, Mercer and his daughter Rebekah first backed the candidacy of Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, in the presidential race; Cambridge worked on Cruz's behalf. When Cruz lost, the Mercers turned their attention to the campaign of Donald Trump - after Trump's campaign also hired Cambridge.

The pattern-seeking mind swings into action. Did Trump win because of Cambridge's use of data scraped from Facebook? Did Cambridge deploy the dirty tricks it was accused of using in developing countries? Was Cambridge the connection between the Trump campaign and the Russians (as special counsel Robert Mueller is apparently investigating)?

On Tuesday, The Washington Post reported that the founding of Cambridge overlapped heavily with another prominent figure on the web of Trump-Russia connections: Steve Bannon.

Along with Cambridge, the Mercers invested heavily in Breitbart News, for which Bannon served as CEO before joining the Trump campaign in August 2016. (He joined the campaign, incidentally, after Rebekah Mercer button-holed Trump at a fundraiser in the Hamptons.) Bannon was tapped to serve as vice president of Cambridge and, according to former Cambridge employee Chris Wylie, was instrumental in guiding the company's initial research in the United States.

From The Washington Post report:

"In focus groups arranged to test messages for the 2014 midterms, these voters responded to calls for building a new wall to block the entry of illegal immigrants, to reforms intended the 'drain the swamp' of Washington's entrenched political community and to thinly veiled forms of racism toward African Americans called 'race realism,' [Wylie] recounted."

"The firm also tested views of Russian President Vladimir Putin."

The research also included responses to the idea of the "deep state," Wylie said.

Interestingly, while Bannon purportedly sought to ask Americans their views of those phrases, they never made their way into Breitbart's reporting. There was one mention of "drain the swamp" on Breitbart in 2014, according to a search of the site on Google. That was in a quote from a former Senate candidate in Louisiana. There was only one mention of the "deep state," in a July 2015 article about Turkey. The only mention of "race realism" came last December.

But that research into Putin, in particular, raised eyebrows. Why would Bannon and Cambridge Analytica be asking Americans for their views on the Russian president?

As is often the case with components of elaborate conspiracy theories, the answer is probably simpler than it may seem. In March 2014, Russia invaded Crimea, shortly after the Olympics in Sochi. In the weeks prior to that invasion, Putin was regularly praised by conservatives for his strong leadership, including by former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani. It is not clear when in 2014 the Cambridge focus groups were conducted, but it's not entirely surprising that, looking for messages that would broaden the conservative base, Americans would be asked about Putin to the exclusion of other world leaders. Over the course of the 2016 election, Republican approval of Putin continued to rise.

Mastery of the dark arts was clearly part of Cambridge's sales pitch. As Vox reports, SCL actively encouraged the idea that it was akin to a Bond supervillian by creating war rooms meant to evoke movie sets. In secretly recorded interviews with Cambridge executives released by Britain's Channel 4 News this week, Cambridge CEO Alexander Nix bragged about setting up political opponents with bribes and sex scandals and insisted that his firm's tactics were central to Trump's campaign. Another Cambridge employee discussed how the company would spread negative information through outside groups as a tactic in the U.S. election.

This is a role that Bannon used to fill. After Trump's victory, Bannon was cast by many on the left as the shadowy Emperor behind Trump's Darth Vader. Bannon encouraged this idea, though to Vanity Fair he compared himself to Vader. On "Saturday Night Live," he was unsubtly (and, generally, unamusingly) depicted as the Grim Reaper, the real power behind the presidency. So running a thread from Bannon to Cambridge to Russia is, for conspiracy-pattern-seekers, irresistible.

The tricky position for Trump defenders is that it's so easy to run those threads. Cambridge and Bannon want to be seen as political puppeteers because it's beneficial to them from a marketing standpoint. Now that people are actively looking for puppet strings, that sales pitch becomes a liability.

But it's important to differentiate the real links - campaign adviser George Papadopoulos being told that the Russians had dirt on Hillary Clinton, for example - from the Hollywood-"Beautiful Mind" ones. The writers of the film would put Cambridge at the center of Russian collusion, sure, but this isn't a film.

By assuming that Cambridge and Bannon were dark masters, we miss the reality of how Trump won: appeals to disenchanted Americans worried about changing demographics that leveraged mass media effectively. Cambridge and Bannon have shown little to no ability to actually win elections. By looking for the movie plot, we ignore what actually happened.

Hucksters, like psychics, are happy to insinuate dramatic connections that will appeal to Trump opponents. It's worth remembering that reality is rarely so elegant.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author