The tweet came Tuesday night, from President Donald Trump, Romney's nemesis for the past few years. It was a formal endorsement of his candidacy. "Thank you Mr. President," Romney tweeted back, in partial reply. The exchange drew a flood of Twitter commentary, mostly unfavorable toward Romney, recalling all the critical things he had said about Trump during the 2016 campaign and since.

When the first rumors of Romney's interest in running for Senate surfaced months ago, there was speculation that he was doing so to become the leading voice among elected Republicans in opposition to Trump. Tuesday's small moment (which Romney must have anticipated as a possibility) suggests that, while such speculation is not entirely misplaced, it is certainly premature and likely far too expansive in its expectations.

Romney has had a full life. He made a fortune in business, saved the 2002 Olympic Winter Games (in Salt Lake City), served one term as governor of Massachusetts, twice sought the presidency and once captured his party's nomination (and believed he was going to win). What motivates him, at age 70 and with two dozen grandchildren, to decide to submit himself to the rigors and occasional tedium of a statewide campaign for a lower office and then the potential frustrations of life in a broken Senate?

One is obviously a belief in public service and a personal desire to serve. Helping the people of Utah has to be another. Ambition certainly plays a role. And there is the ability to make his voice heard in ways that private citizens, even those who were presidential nominees, cannot achieve.

As a presidential nominee, he learned the value of being able to be heard. He got a small taste of that again in 2016 as an outspoken critic of candidate Trump, even though, in the end, he, like other Republicans who spoke out, proved powerless in trying to stop the New York businessman's march to the presidency. The further he is removed from those experiences, the less his voice will be heard.

Meanwhile, voluntarily stepping fully away from the arena is sometimes more difficult than stepping back in. You can see that in others who have reached a somewhat similar stage and age in life, among them former vice president Joe Biden, who for now will neither rule out or in a race for the presidency in 2020.

Romney is fortunate that a Senate seat has opened up in a state where he has roots, relatives and a current residence, though his opponents will label him an opportunistic carpetbagger. Romney had been positioning himself well in advance of Sen. Orrin Hatch's retirement announcement, quietly plotting and planning for a campaign should the opportunity arise.

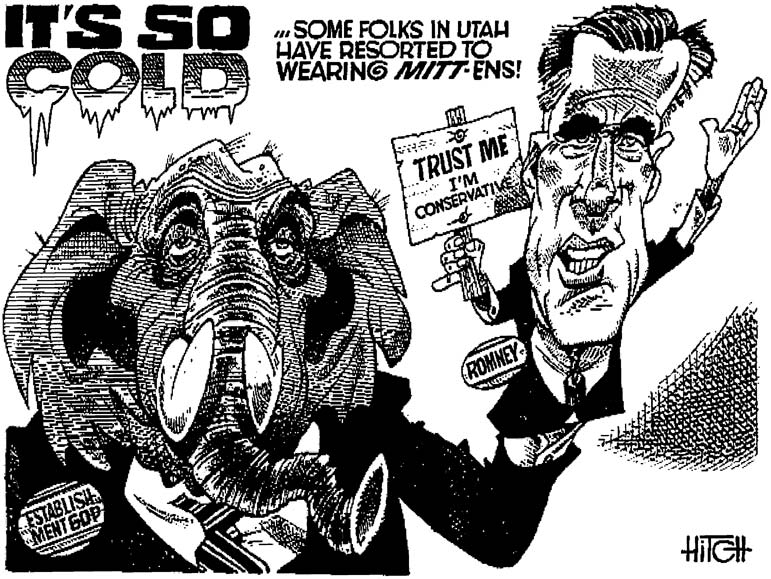

But for what purpose? In truth, Romney's differences with Trump as president have been much more on matters of behavior and much less on matters of policy. Romney has staked out differences with the president on foreign policy, including Russia, even though he talked with Trump about becoming secretary of state. But he likes the new tax cuts and supports the administration's deregulation efforts. "For the most part, the policies are coming out of Congress and signed by Trump; he's pretty good with those," one Romney ally said.

But the differences on other matters are serious and important. Romney is concerned that Trump, through policy and behavior, threatens to redefine the Republican Party as one that is tolerant of racism, one that turns a blind eye to sexual harassment or abuse, one that is insensitive in other matters, as well.

Last summer, Romney condemned the neo-Nazi marchers in Charlottesville, Virginia, when the president said some were "good people." He spoke up in defense of Leigh Corfman after she accused Senate candidate Roy Moore of sexual misconduct when she was 14. Trump backed Moore in the Alabama race. Romney said he believed Corfman. Last month, he criticized Trump for using a vulgarity during an Oval Office meeting on immigration to describe some nations.

Many months ago, some allies of Romney warned him that, if he were to run for the Senate, he should not do so simply to oppose the president. In opening his campaign, he has clearly taken that advice to heart. His announcement video was Utah-centric and heavy on references to "Utah values," among them balanced budgets, a message of inclusion rather than exclusion for immigrants and political leaders who treat one another with respect.

The line about inclusion was a veiled reference to Trump but carefully enunciated. It was also a reminder that he comes to the Senate campaign with a record of actions and statements on issues from his term as governor and his two presidential campaigns. On immigration, that includes his infamous "self-deportation" comment about how to deal with the millions of undocumented immigrants in the country (which he said later was not meant to sound punitive) and his criticism of President Barack Obama for using executive action to protect the young undocumented immigrants known as "dreamers."

Romney's video is an indication of how his campaign for the Senate will begin to unfold, which is to say locally rather than nationally. He will travel the state, seeking to show that he is serious first about the needs of Utah. Local reporters will get preference over national outlets. His tweeted "thank you" to Trump included a statement that he hopes to "earn the support and endorsement of the people of Utah."

As with other Republican candidates who have differed with Trump, he could be pressed and perhaps hectored by the president's loyalists in the state, though Utah was hardly a hotbed of Trump support in 2016. He also could be pushed by others to make his differences with the president more explicit. Once in the Senate, he would find himself trailed by reporters, recorders and cameras thrust in his face, asking for responses to any and all controversial comments by the president.

Some Republicans see him as a possible primary challenger to Trump in 2020, but that, too, is speculative and a long way off, given unfolding events for Trump, pro or con. Still others wonder whether Romney would take on the same kind of role in the Senate as Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., an outspoken proponent of "America Engaged" rather than "America First." Though Romney's and McCain's personalities are entirely different, their internationalist world view, and hostility to President Vladimir Putin's Russia, are in sync.

As a former governor, Romney could quickly discover that the slow-moving and often unproductive Senate is constraining and frustrating. He and others are thinking about how he could best use the position, for Utah (think land issues, for example) and for issues about which he is personally passionate (foreign policy among them).

For those who hope Romney runs primarily out of pique toward the president, there will be disappointment - as the exchange Tuesday night showed. But there will be disillusionment among those who admire him if he shrinks from truly standing up as needed to the president. Romney has some months to think all this through. Still, his goal cannot be to go to Washington as a junior senator and to act like a back-bencher. Eventually, should the voters of Utah embrace him, he will have to decide what kind of leader of Republicans he wants to be.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author