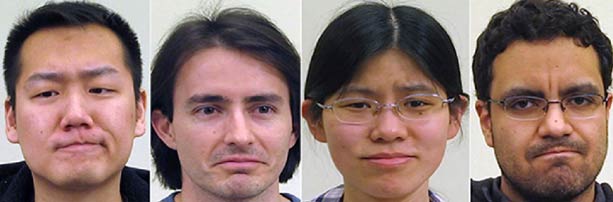

A furrowed brow, pressed lips and a raised chin: the not face. Credit: Ohio State University

A furrowed brow, pressed lips and a raised chin: the not face. Credit: Ohio State University

Scientists are investigating something they call the "not face" -- and they think it may provide clues as to how human language first developed. The study, published Monday in the journal Cognition, suggests that the expression is a universal grammatical modifier -- not just an unconscious expression of emotion.

First, a little bit about the "not face." We all make it. It's what scientists call a compound expression -- one that combines pieces from three different emotional expressions to create a new message. It takes components from anger, disgust and contempt.

It's a face that says "um, no." It's an instant expression of total disagreement. According to study co-author Aleix Martinez, a cognitive scientist and professor of electrical and computer engineering at Ohio State University, the not face shows more than just our species' ability to express complex emotions. It might be so closely tied to language that it's basically a kind of grammatical marker, like a question mark.

"A grammatical marker is a sound or facial expression or sign that has some grammatical function, and these things distinguish animal communication from human language," Martinez told The Washington Post. Scientists are always looking for true grammar use in non-human animals - some suggest that birds use grammar - because they're not sure how humans evolved this unique communication trait. Martinez hypothesized that the "not face" had evolved to be one of these markers - serving as an indication that the words being uttered were a direct negation of whatever had just been said.

Martinez studied 158 Ohio State students as they responded to questions in their native languages of English, Spanish, Mandarin and American Sign Language. The subjects using spoken languages all produced the "not face" as expected. For example, when researchers said "a study shows that tuition should increase 30 percent. What do you think?" the students answered as negatively as one would think, and had the tell-tale combination of disgust, contempt and anger showing on their faces as they spoke.

But anyone can make faces while they talk. The coolest indicator of the grammatical nature of the expression came from the ASL speakers.

"In fact, we saw that in sign language in particular, sometimes the sign for "not," which is usually signed with the hand, was omitted, and that facial expression of negation was used instead," Martinez said. "In some cases the only way you'd know the sentence was negative was that facial expression."

Testing this was "very clever," according to Alice O'Toole, a University of Texas at Dallas professor specializing in face perception who wasn't involved in the study, and "makes for a pretty solid case."

O'Toole said that the study was one of several in recent years to highlight the importance of watching lip movement during speech. "In evolutionary terms, we tend to think about language overtaking expression and non-linguistic vocalization as the primary form of human communication - and forget the importance of facial expression . . . in understanding how humans ultimately ended up evolving toward language," she wrote in an email.

In other words, a lot more goes into understanding a conversation than just listening to the sounds being strung together. Facial expressions evolved before verbal communication, but understanding how they've come to work in tandem could help researchers puzzle out the origin of human speech's unique qualities.

Previously:

• 03/21/16: These birds use a linguistic rule thought to be unique to humans

• 12/09/15: Study confirms that ending your texts with a period is terrible

Comment by clicking here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author