In a call center, somewhere on Earth, a telephone rang. John picked up. On the other end of the line was a man who spoke in a preposterously fake Russian accent and introduced himself as "Vicktor Viktoor," which was not his real name.

It's very possible that John used a fake name, too, as the call center was in actuality an internet scam headquarters - something "Vicktor" knew very well, though he had no intention of telling John right away.

Not for hours, if he could help it.

John: Thank you for calling online support. This is John, how can I help you?

Vicktor: Hello, John?

J: Yes, how can I help you, sir?

V: John, I have red message on computer from trojan?

J: What kind of message?

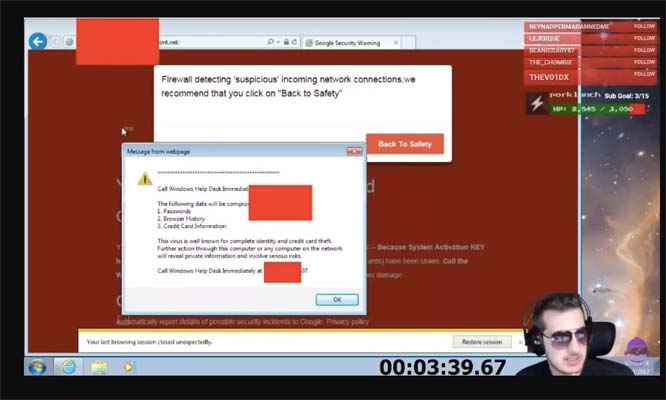

V: It say, from trojan, the IP address hacked, from the Windows? ... It say firewall detect suspicious incoming activities. ... Uh, hold on, it hard to read ...

John waited patiently, though "Vicktor" was not actually having any trouble reading the obviously fake security alert that had popped up on his web browser that night.

It warned that a virus was going to steal his credit card information unless he called a 1-800 number for a "help desk" - which "Vicktor" had happily done, while secretly live-streaming the call to several hundred viewers.

Vicktor's fans know him better as Kitboga, one of the most popular scam baiters on Twitch.

Kitboga spends hours each week playing computer-illiterate characters such as Vicktor for the purpose of wasting the time of people like John, who each year defraud millions of people out of hundreds of millions of dollars through tech support scams, IRS scams, email scams - scams of all kinds.

Kitboga has to keep his real name a secret, he told The Washington Post, because scammers sometimes threaten retaliation when he confronts them at the end of his calls.

He would confront John that night in September - though not before "Vicktor Viktoor" tormented him for two full hours.

John: OK, not to worry sir. We are going to check all the issues for you ... Can you please tell me one thing, the computer you are using? ... Dell? H.P.? Toshiba?

Vicktor: I do not know. It think it is Windows?

J: There is a Microsoft Windows key with four little boxes on it. You see that?

V: I see flag. Is this what you mean?

J: On the keyboard! On the keyboard.

V: Yes, I see flag.

The standard M.O. in a tech support scam, as the Federal Trade Commission explains it, is straightforward.

The victim, often elderly, is fooled by the pop-up warning and calls the "help center."

A fake technician, like John, answers the phone and efficiently guides the victim to a website that gives him remote access to their PC - as if he was sitting at the keyboard himself.

Then the scammer does, basically, whatever he wants.

In John's case, he intended to convince Vicktor to buy hundreds of dollars in bogus anti-virus software - when the real stuff is often free - and in the process obtain his credit card, Social Security number and bank information.

But 15 tedious minutes into the call, it wasn't going so well.

John: Type W ... W ... W ... dot ... After dot, put help. H ... E ... L ... P. Help.

Vicktor: P like pneumonia?

J: (pause) Yes. ... Then after the dot, put N ... E ... T.

V: You say M-E-D, like doctor?

J: T like tomato.

V: D like domato?

Keystroke after agonizing keystroke, John guided Vicktor to the site that would let him infiltrate his PC. But Vicktor's hearing progressively worsened, and a 15-minute call became half an hour, then longer still.

Kitboga sometimes covered his mouth to stifle a laugh.

On his Twitch channel, his fans watched a timer count every millisecond of the phone call. Kitboga was trying to set a personal record that night.

"We've noticed around the one-hour mark, the technicians start to get really nervous," Kitboga told The Washington Post, speaking from his home in an undisclosed location, where he lives with his wife and dog, working by day as a software engineer. "Maybe their bosses tell them they have to close the sale by then."

Scam baiters have been around at least since the mid-2000s, when the Atlantic profiled some of the first networks of do-gooding trolls.

At the time, the most common internet scams worked through email - elaborate stories of deposed foreign heirs, like the perennial "Nigerian prince," who promised the victims great riches if they forward their confidential bank information.

Kitboga's late grandmother was a victim, he told the Daily Beast in a recent profile. The anger he felt upon learning that led him to scam baiting last year, and it soon became his passion.

Every so often, he said, he gleans enough information about an operation to report it to the U.S. government. But he's very aware of the entertainment value in his ruses, and has attracted hundreds of thousands of views since turning his sessions into a Twitch show several months ago.

"It's weird to say I was so excited about something like that, because it's a sad situation," Kitboga told The Post.

After wasting the better part of an hour, John finally got access to Kitboga's computer, not realizing it was merely a virtual desktop filled with bogus personal information. The desktop background was a picture of Vladimir Putin, to lend authenticity to Vicktor's supposed Russian origins.

Taking control of the cursor, John opened a standard Windows settings menu to show Vicktor what he called "security" vulnerabilities, which could have been easily fixed free with a few clicks of a mouse.

Instead, John opened a notepad file on Vicktor's screen and pasted in a long list of nonexistent problems.

John: Sir, right now as your computer is totally damaged, we'll have to go ahead, and we'll have to do the complete fixation of the computer.

Vicktor: OK, you speak a little slower for me. I can't understand.

J: (slower) Yes, sir. ... We're going to give you protection ... from all the type of viruses ... and all the type of trojans ... and all the type of malware. Each and every thing will be fixed for you.

V: Does your mother have the same security?

J: (long pause) Yes, sir.

V: John, please talk slower.

J: Sir ... we have ... to remove ... all ... koobface ... worms ...

Kitboga made John explain to him the difference between a pop-up window and Papa John's pizza.

He laboriously questioned each and every technical term John threw at him, as the scammer tried to talk the scam baiter into buying anti-virus software for the senior-discounted price of $1,119 - plus tax and installation.

After more than 45 minutes on the phone, John finally obtained a working credit card number.

Of course he didn't know it was a gift card with 40 cents on it, and hit another major roadblock when he asked Vicktor for the three-digit security code on the back.

John: There ... are ... three -

Vicktor: John, I have the phone close to ear. I need you to whisper, quiet.

J: (whispering) Sir, there is three digits on the back side of the card.

V: For phone number, you say? It is 1-800-847-29 ...

J: No. No, no, no, no, no.

Kitboga never knows how long he'll be able to keep a scammer on the line, or what will happen in the interim.

As his Twitch audience grew into the hundreds of thousands late last year, his voice would sometimes be recognized - like the time a scammer saw through his character "Clark P. Witherspoon," cussed him out and hung up on him.

Kitboga now often uses voice-altering software to enhance his disguises.

As "Edna," a character modeled off his late grandmother, he once charmed a scammer into opening up about his personal life - his little brother, his fear of ice skating. Edna invited the man to visit her some time. She'd teach him to skate.

The scammer said he'd love to, then resumed instructing her to install spyware on her computer.

But the call with John in September was relatively early in Kitboga's scam baiting career, so "Vicktor Viktoor" and his ridiculous accent still sufficed as bait.

An hour-and-a-half into the call, John couldn't understand why Vicktor's credit card number kept getting declined. He was trying to get Vicktor to call his bank and authorize the payment, but Vicktor was increasingly distracted by his fictional cat, which needed its catheter changed.

Kitboga's Twitch audience often suggests fantasy scenarios for him to use on the scammers.

John eventually became so flummoxed that Vicktor was transferred to a different scammer in the call center. But Kitboga wouldn't let his target go that easy.

Woman: I'm from the billing department. John was not from the billing department.

Vicktor: I only trust John. He help me very much. Where is the John?

The woman relented and put him on hold.

V: Is this John?

John: (slight sigh) Yes, sir.

For another half-hour, with increasing desperation, John lowered the price from $1,119 to $800, and finally $399.99.

Again and again, he typed Vicktor's fake address (42 Walleby Way, Bayonne, New Jersey) into a web form.

But the charge never went through, and Vicktor's questions never ceased.

Vicktor: John, how much longer this take? You say you are Microsoft professional, and it take forever.

V: John, tell me about yourself. What was little John like when you were young?

V: John, I hear wind. You are outside?

John: Everyone breathes, sir.

Finally, nearly two hours into the call, John gave up.

"You can hang up, OK?" he told Vicktor.

Vicktor's accent instantly disappeared.

"John, thank you so much for spending, like, almost two hours with me," Kitboga said. "I don't know if you'd be willing to just talk for maybe another five minutes or so."

When he confronts scammers, Kitboga told The Washington Post, he never does so in anger. He has read too many articles suggesting that the people who answer the phones - whether the call center is in Florida or India - are rarely the masterminds of the scam.

Sometimes they are desperate for money. In some cases, the Guardian reported, they don't even realize they're deceiving people. Maybe John thought anti-virus software really did cost as much as a new PC.

So for his last question of the night, Kitboga asked John with kindness in his voice: "How'd you get caught up in that?"

John just hung up, but Kitboga noticed he still had remote access to his computer. So he opened the fake help center chat window and typed:

john

please think about what you are doing

when you go home tonight

this is a lie

It was four minutes past midnight on Sept. 20. The call had lasted just under two hours - a personal record for Kitboga.

In the months since, he told The Washington Post, he's topped it by more than an hour.

World Record 2 Hour Scam Call With Angry Tech Scammers:

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author