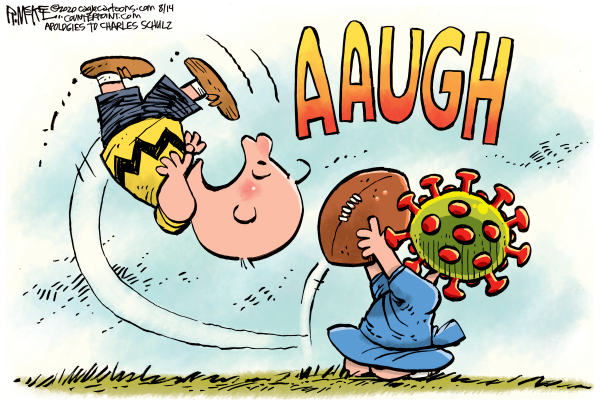

As schools struggled with these unprecedented challenges, 2020 gave us a glimpse into what's considered truly essential in higher education: Football. With the College Football Playoff getting underway on Friday, we're seeing how many of America's preeminent centers of learning have treated their programs as hallowed ground, with their teams' status arguably heightened during this tumultuous season.

Even in the best of times, the vast majority of U.S. universities know they can never hope to have the academic standing of a Harvard or Stanford, but they can dream the next best thing — having a football team like Alabama's or Clemson's.

Success in college football isn't just about bragging rights. It's about money, visibility and attracting talent to all departments on campus. The Southeastern Conference, home to the University of Alabama, recently signed a television rights deal with Disney's ESPN that will pay the conference $300 million per season, more than five times the conference's current $55 million per season deal with CBS.

When factoring in all revenue sources, the top college football programs are now bringing in over $100 million a year per school, more than double the annual revenue of an average Major League Soccer team and close to an average National Hockey League team.

Add to that the impact on a college town's local economy, as tens of thousands of alumni and fans swarm to town for game day. Those Saturdays in the fall mean hotel stays, restaurant and bar spending, jobs for workers and tax dollars for local governments.

Higher visibility from sustained college football success can be a key component of a school's long-term growth plan. The University of Alabama's multiple national championships over the past several years has allowed it to recruit students from all over the country to raise its academic profile. The same goes for Clemson in South Carolina, where applications to the school increased by 86% between 2008 and 2018 as its team made the national finals in four of the past six years, clinching the title twice.

Aspirations extend beyond the name-brand schools. Liberty University, known best for its ties to evangelical leaders Jerry Falwell Sr. and Jerry Falwell Jr, grew its endowment to over $1 billion by expanding its online-class business. It's used the money to build up its football program in hopes of becoming to evangelicals what Notre Dame is to Catholics. The school recently completed its most successful football season ever under Coach Hugh Freeze, whom they lured away from major conference schools with a multimillion-dollar contract.

This is an uncomfortable development for proponents of the educational mission. Incentives drive behavior, and if it's football that universities are dependent upon for their success, then football will increasingly call the shots. Whether they'd admit it or not, universities pushed to reopen their campuses this summer with the college football season in mind. Two of the major athletic conferences, the Midwestern-centric Big Ten, and the Pac-12, initially decided not to play the football season, only to reverse their position as other conferences decided to move forward, perhaps out of fear of being left behind.

Even at schools with successful football teams, non-football budget cuts are still happening. Despite the additional revenue generated by its program, Clemson decided in November to cut its men's track-and-field and cross-country teams. And the University of Alabama athletics department cut its operating budget last year, in part because of the lost revenue from reduced football attendance this season.

What comes next for higher education may be the same sort of K-shaped recovery that the rest of the economy has gone through this year. The top 25 universities in the country with national or global profiles and multibillion-dollar endowments will find themselves continuing to be the preferred landing destinations for top students and faculty.

Another tier of universities will find themselves in an ever-escalating arms race for the kind of success in college football that can power a university and a local economy. And for too many others, it will be a downward spiral of lower revenues, budget cuts, enrollment declines and, ultimately, closed doors.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Previously:

• 12/31/20 Just send the bigger bucks already

• 08/24/20 Young people can't buy homes until older owners . . . move on

• 08/18/20 Our pandemic love affair with e-commerce could soon sour

• 08/10/20 Booming 'zoom towns' should ease city housing costs

• 07/11/20 With a Biden economy, will America be condemned to relive the '70s?

• 07/14/20 Renting and homebuying swap roles in the covid-19 market

• 07/13/20 Markets may have a reason to rise along with covid-19 cases

• 04/27/20 U.S. economy may have hit the coronavirus bottom

• 11/12/19 The 2020 economy should feel a lot better: What to, realistically, expect

• 04/23/19: Gen Z is likely to temper aging socialist millennials

• 03/25/19: All signs point to a housing boom ahead

• 02/19/19: Trump's economic gamble might make sense

• 02/15/19: Scaring off Amazon will backfire for the Left

• 01/29/19: The 2020 election will shred the Obama coalition

• 11/15/18: Amazon proving the 'rich get richer'?

• 11/13/18: How gerrymandering can reduce the partisan divide

• 10/22/18: The politics of the next recession will be a disaster

• 08/02/18: The future of the US looks a lot like ...

• 05/05/18: Brick-and-mortar stores may start to make sense again

• 05/05/18: College admissions season is about to get much easier

• 05/03/18: Changing housing needs of millennials will change economic development

• 02/13/18: The big idea for Middle America is to think small

• 02/07/18: Dems are caught in a tax bill trap this year

• 10/25/17: Good times have come to Trump-leaning states

Sen is a portfolio manager for New River Investments in Atlanta and has been a contributor to the Atlantic and Business Insider.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author