When campaign season opened early last year, the party's progressive wing appeared ascendant. Sens. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., were seen as two of three or four top-tier candidates. Medicare-for-all, a proposal first championed by Sanders, was drawing support from other candidates. A costly Green New Deal to combat climate change was on every candidate's list of must-do policies.

As the year progressed, both Warren and Sanders had ups and downs. She struggled early but caught fire over the summer and led the Iowa Poll in September. Then she hit a rough patch and slipped back.

Sanders showed his fundraising prowess in the early months of 2019 but appeared to be fading as the year progressed. After suffering a heart attack in October, he unexpectedly bounced back. The Iowa Poll released a week ago showed him leading the pack just weeks before the caucuses.

Through the course of the year, the debate over health care shifted. Medicare-for-all no longer was a consensus position. Former Vice President Joe Biden, former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Sen. Amy Klobuchar, the other three candidates in what currently constitutes the top five in Iowa and New Hampshire, all favor adding a public option to the Affordable Care Act rather than Medicare-for-all. Warren, after saying, "I'm with Bernie" on the issue, now calls for interim steps before trying for a full, single-payer plan.

This week, the progressives found themselves with a new problem when Sanders and Warren got into a scrap over a private conversation they had in December 2018. Warren says that Sanders told her a woman could not win the presidency. Sanders says he said no such thing. The two discussed the matter during Tuesday's Iowa debate without real fireworks.

Afterward, however, with their TV microphones still turned on, Warren walked up to Sanders, refused to shake his hand and said, "I think you called me a liar on national TV." A flustered Sanders said they should hash it out at a later time.

Some progressives have hoped both candidates would remain as viable as possible for as long as possible - and as respectful toward one another as possible - if only to give the left more influence at what some Democrats believe could be a nominating contest in which no candidate gets a majority of delegates ahead of the national convention in Milwaukee.

An internecine struggle between Warren and Sanders is the last thing many in the progressive movement want to see, although it was inevitable that the two candidates would find themselves in conflict for support of liberal voters in the Democratic primaries and caucuses. Given what happened in the debate in Des Moines, peace in the family seems more elusive.

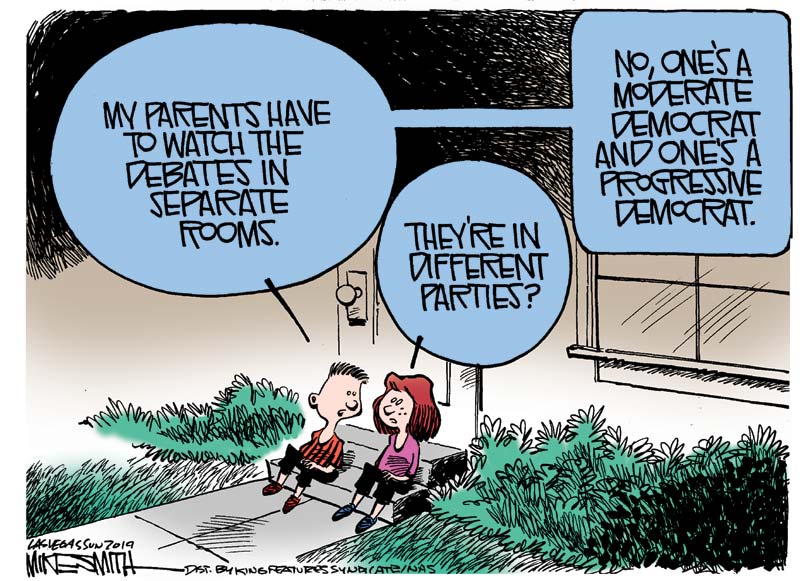

What does the past year say about the state of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party? That starts with the question of just what the progressive movement is and the answer, based on conversations with people in various organizations on the left, is that the progressive movement today is an amalgam of groups with some shared purposes but with no clear center of gravity.

There are the traditional power bases of organized labor, the industrial unions and the service and teachers' unions in particular. But labor is not as powerful as it once was due to shrinking membership, some internal problems and the reality that many union workers like President Donald Trump.

In the Democratic presidential campaign, most national unions are remaining neutral, waiting to see what the voters are thinking. Beyond the labor movement, there are long-standing environmental groups or women's or campaign groups, liberal fundraisers, as well as data, media and political organizations that wield some power.

There are also newer entrants, disrupters to the older order who tend to operate outside the Democratic Party structure but who have a growing voice. "There are these super, young activists who are pushing this progressive movement in ways you haven't seen before," said one Democratic strategist associated with the Sanders candidacy.

Assessing the progressive wing of the party in the context of the presidential campaign takes two forms: issues and candidacies. On the issue front, many progressives feel optimistic about where they have made gains and where things are heading. "The ideas in the Democratic Party have really moved significantly toward the progressive side," said Andrew Stern, former president of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

Progressives point to climate change, where the candidates' proposals are far more ambitious than they were just a few years ago. Democratic candidates also are offering more aggressive policies to deal with wealth and income inequality. Also notable is the fact that candidates almost uniformly are more forceful in advocating for stronger labor protections and workers' rights. Even on health care, though the debate may have shifted toward the center, that center is farther left than it was four years ago.

Many Democrats who are more in the establishment wing of the party play down the differences on issues, arguing that Democrats of various ideological stripes are in general agreement and that policy debates are not tearing the party apart. Still, George Goehl, who leads the group Peoples Action, which has endorsed Sanders, said, Democrats are "set up to have the most progressive platform like ever."

What tempers this otherwise positive assessment of the state of the movement, and what worries some on the left, is the practicality with which many voters, including those who are most liberal on the issues, are approaching their choices of a candidate.

Ideas may be moving in one direction, but the realities of the electoral map - the states likely to decide the outcome in November - are pushing some voters to put a greater priority on electability and therefore settle for a candidate who is less progressive.

"One thing that was very clear at the beginning of [2019] and remains true today is that electability is the threshold question even for the most progressive primary voters," said Adam Green of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, which backs Warren. "All other factors for decision making come after candidates meet that electability threshold." Green said that is cause for concern.

The conflict between Sanders and Warren is not insignificant. The two have similar diagnoses of what ails American capitalism and the current political structure, but they offer different prescriptions for fixing things - and they are stylistically different.

The larger issue for progressives is the ultimate choice of a nominee, which is the looming battle as the primary season moves forward. Will Democrats pick a Warren or a Sanders, or will they decide the safer and better choice is a Biden or Buttigieg or Klobuchar or maybe former New York mayor Mike Bloomberg, none of whom are the kind of boat-rockers than the two leading liberals would be and that progressives would like.

The strength and gains of the progressive movement are plainly evident, but so too is the worry among some in the movement that they could fall short of their political aspirations.

As Steve Cobble of Progressive Democrats for America put, "There is a split between those who say it's time to go big and take it and those who are scared to death that Trump will get four more years. Realistically neither side can prove the other wrong." Which is why the roller coaster ride isn't over.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author