A prime example emerged recently when a federal judge in New York City threw out the Commerce Department's plan to add a question to the survey for next year's census.

Questions for the census come and go through the years, reflecting changes in society during the 10 years since the previous population count.

When the country was largely rural, for instance, the census asked about the acreage of specific crops. The first national headcount in 1790, which found 3.9 million people in 13 states, also inquired how many white women and slaves lived in the household.

On its face, the new census question is quite simple really, asking if the respondent is a U.S. citizen. It was a short-form census question until 2010, when President Barack Obama deleted it.

Citizenship does seem reasonable enough to document since each state's counted population is used to apportion its fair share of the set 435 members elected by citizen voters to the House of Representative, adjusted every 10 years.

As you might imagine, however, nothing is simple in this age of contention.

Various groups sued Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross and his department, claiming the question was intrusive and would likely intimidate and deter many noncitizens from answering, especially if they're among the estimated 25 million illegal residents.

Some of us would suggest this is fine. They're not supposed to be here anyway. You have the right to remain silent. You do not have the right to vote and, as an illegal resident, you certainly should not have the right to be represented in Congress.

As you may have noticed, such people tend to congregate in areas governed by elected Democrats, who often champion their causes, including driver's licenses and sanctuary cities and oppose things such as voter ID based on proof of citizenship.

So, a dramatic under-counting of people, those here legally and illegally, would likely reduce a state's potential shares of federal monies based on population and House representation (of Democrats).

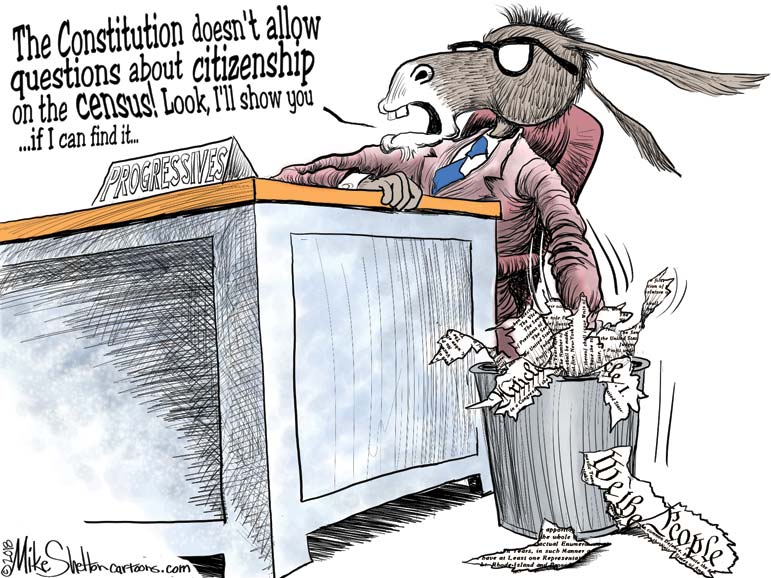

Here's a little-known twist: The census is indeed required by the Constitution. But it mandates counting only "Whole people," as opposed to slaves, who counted as just 60 percent of a person back then, and Native Americans, who didn't count at all.

Since so many residents of the 13 new United States had originated elsewhere anyway, the question of immigrants and citizenship was not enumerated. Court rulings since have interpreted "Whole people" as everyone, regardless of citizenship.

Plaintiffs in the New York case also suggested Ross is likely racist, an eyeball-rolling charge routinely leveled by the left at people or things it doesn't like. The judge tossed that claim. But he did rule that the Commerce Department settled on the citizenship question without dutifully following statutory procedures.

Speaking of this district court judge, he's Jesse Furman, a native New Yorker and another of those Ivy League lawyers who seem able to flock so easily to perches of power and authority in the East.

You may have read in the media that he was appointed in 2011 by Obama. That's true. You likely did not read that Jesse Furman is the brother of Jason Furman, another Harvard guy who was — wait for it — chairman of Obama's Council of Economic Advisers.

That's how these lifetime appointments are routinely distributed out of Washington. Someone knows someone of like mind who once clerked for someone else of like mind. Perhaps you noticed the Bush links during Brett Kavanaugh's Supreme Court confirmation last fall.

That's how those established interests prolong their power.

This all helps explain the singular focus of former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and now Mitch McConnell on pushing the confirmations of federal judges through that chamber.

Those judges are the ones whose legal interpretations end up making or unmaking laws the rest of us will live under for decades. Judge Furman is only 46.

During his 417 weeks in office, Obama appointed 329 federal judges at all levels, a number of whom like Furman have ruled adversely on President Donald Trump's initiatives.

During his 104 weeks in office, Trump has appointed 84 federal judges of all kinds. Thirty-one more Trump judicial nominees await Senate action.

Now, back to the census case. Without a time-consuming appeal, the citizenship question is dead. But coincidentally, the Supreme Court had already scheduled a Feb. 19 hearing on a now-moot part of the same case.

Administration lawyers, citing the summer deadline to begin printing census questionnaires for the country's estimated 325 million current residents, will likely ask the court to consider its New York appeal then instead.

If it's about an administration's right to draft census questions, Trump will likely prevail. If it's about the question-drafting process, maybe not. Despite social media outrage, citizenship will not matter, even if determined.

But wait. One of the liberal Supreme Court justices, 85-year-old Ruth Bader Ginsburg, remains at home after cancer surgery. And Trump appointed two of the other eight for their strict constructionist histories.

So, what likely ends up mattering most in this controversial case that could determine congressional representation for the next decade is a census of just nine whole people.

(COMMENT, BELOW.)

Andrew Malcolm

McClatchy Washington Bureau

(TNS)

Malcolm is an author and veteran national and foreign correspondent covering politics since the 1960s.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author