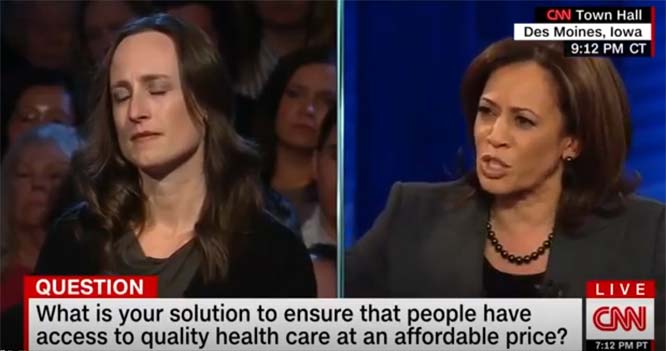

When Sen. Kamala D. Harris spoke about health care at a CNN forum Monday evening, she threw her support behind a "Medicare-for-all" plan, sounding similar to other candidates seeking the Democratic presidential nomination.

But when pressed for details, the senator from California explained the idea in a way most Democrats assiduously avoid: She agreed that Medicare-for-all also means private insurance for none.

"Let's eliminate all of that," Harris said, referring to private health insurance. "Let's move on."

In a single flourish, Harris, D-Calif., drew attention to the fact that the Medicare-for-all plans backed by 16 senators - including five candidates or potential candidates for the Democratic nomination - would in effect remove private health insurance from the estimated 251 million Americans who use it, broadly disrupting the industry and the way Americans experience the medical system.

The concept drew quick rebukes from Republicans - and billionaire coffee magnate Howard Schultz, who is considering an independent presidential bid - showing how easily the idea can be weaponized politically, especially as candidates are increasingly pressed for specifics.

"That's not American," Schultz, the former Starbucks CEO, said on CBS News. "What's next? What industry are we going to abolish next? The coffee industry?"

The details of how exactly to overhaul the American health care system have long befuddled presidential candidates - and presidents - of both parties. The issues are complicated and difficult to reduce to sound bites.

On the campaign trail, candidates often hear complaints from voters frustrated by rising drug prices, staggering and widely inconsistent medical bills, skyrocketing deductibles, unaffordable premiums, and difficult-to-conquer bureaucracies, creating pressure to offer a sweeping overhaul plan.

But the candidates' slogans inevitably prove difficult to implement. And often it's not exactly clear what those slogans meant to begin with.

Republicans tried repeatedly to repeal the Affordable Care Act but could never agree on how to replace it, resulting in a politically embarrassing failure. Before that, President Barack Obama pledged when selling the ACA that "if you like your health care plan, you'll be able to keep your health care plan," a comment later widely criticized as misleading.

The contours of the health care debate have shifted significantly. Just six years ago, when Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., introduced his first Medicare-for-all legislation, it attracted zero co-sponsors.

After making it a central part of his insurgent 2016 presidential campaign, the idea become more popular in Congress. A similar Sanders bill introduced in 2017 drew 15 co-sponsors. Senate Democrats who are running for president or considering a bid who have signed on to the bill include Harris, Elizabeth Warren, of Massachusetts, Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, and Cory Booker of New Jersey.

Sanders, who is also considering a presidential bid, hasn't reintroduced his bill but plans to, according to Josh Miller-Lewis, a spokesman for the senator.

Sanders' legislation would create a new government-run system that would cover all Americans. The new system, which eliminates deductibles and premiums, would be mandatory after a four-year transition. Private insurers would have a small role: They could only cover procedures that the government system refused to preform.

Harris is the first of the top-tier 2020 Democratic candidates to be pressed on the details of Medicare-for-all.

"It will totally eliminate private insurance, so for people out there who like their insurance, they don't get to keep it?" CNN's Jake Tapper asked at Monday's event.

Harris answered, "The idea is that everyone gets access to medical care, and you don't have to go through the process of going through an insurance company, having them give you approval, going through the paperwork, all of the delay that may require."

Harris added that patients would be able to avoid insurers' long approval process and voluminous paperwork.

"Who of us has not had that situation, where you've got to wait for approval and the doctor says, 'Well, I don't know if your insurance company is going to cover this'?" she said. "Let's eliminate all of that. Let's move on."

The plan is estimated to cost $32.6 trillion by 2031, according to Charles Blahous of the "nonprofit free-market-oriented" Mercatus Center.

Candidates can point to evidence that there's popular support for the idea. Fifty-six percent of respondents backed a Medicare-for-all plan, according to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey. The same poll showed that 42 percent opposed it.

But enthusiasm for the idea plummets when respondents are told the plan would largely eliminate private health insurance companies: 37 percent favor eliminating private insurance.

And nearly 70 percent of those surveyed in a Gallup report released in December said they think their health coverage is either "good" or "excellent."

About 156 million Americans obtain health insurance from their employer via a private plan, according to 2017 figures from the Kaiser Family Foundation. An additional 20.5 million buy their own private insurance.

But that's not the full picture: About 20.4 million Americans use a private insurer via the Medicare Advantage program, according to the foundation, and 54.6 million who are on Medicaid are using private plans.

About 28.5 million Americans were uninsured in 2017, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

Experience suggests that voters, despite their complaints about the health system, often react negatively to proposals for sweeping change, possibly because of uncertainty about what would follow.

"The truth is, the vast majority of Americans are getting their health care through private health plans," said Larry Levitt, a senior vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit health care organization. "It would mean a lot of people would have to change how they get their health coverage. That makes people nervous."

The gap between the public's support for Medicare-for-all and its understanding of the details could explain why some Democrats are careful when discussing health care.

Warren didn't include Medicare-for-all in her stump speech on a trip to Iowa after announcing her presidential bid. Asked why, she played down the omission. "No one's raised it," Warren said.

When asked by a reporter on Tuesday about her position, she pointed to her own proposal on health care - one that envisions the continued existence of a health insurance industry. "It's a consumer protection bill around health insurance," Warren said, noting that it requires health insurance companies to offer coverage that is at least as good as the coverage offered by Medicare.

Ian Sams, a spokesman for Harris, said she could support an overhaul that preserves the health insurance industry in some form.

Other similar plans include one backed by the Center for American Progress known as Medicare Extra for All, which would not eliminate private insurance.

House Budget Committee Chairman John Yarmuth, D-Ky., plans to hold a hearing on Medicare-for-all-type plans.

"As we continue to consider what a Medicare-for-All proposal could look like, I believe the potential role private insurance could play is an important part of that discussion," Yarmuth said in a statement.

Another area Democrats have downplayed is the insurance employees whose jobs would be at risk. About 512,000 Americans work directly for health insurance companies, and another 908,000 work in closely related industries, according to an estimate by America's Health Insurance Plans, an industry group.

"I think we could never afford that; you're talking about trillions and trillions of dollars," Michael Bloomberg, the former New York mayor and potential 2020 candidate, said of Medicare-for-all while visiting a factory in New Hampshire on Tuesday. He added that the idea would "bankrupt" the country.

Supporters, however, point out that many industrialized countries have managed to implement some kind of government-run health plan without financial calamity.

"This isn't just about covering everybody," explained Miller-Lewis, the Sanders spokesman. "There are million and millions of people who have health insurance who are still going deeply in debt. It's a huge problem."

Every weekday JewishWorldReview.com publishes what many in the media and Washington consider "must-reading". Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author