Toni L. Sandys for The Washington Post

Toni L. Sandys for The Washington Post

As luck would have it, two NASA satellite experts - David Lagomasino and Temilola Fatoyinbo - saw the request. It mentioned a tree study Goldberg had done that involved climate change and measuring the growth of maple seedlings in her backyard once a week for three years.

The two NASA scientists were intrigued. "This girl sounds great," Lagomasino recalls saying. "We have some work to do, let's bring her in." Even at a large governmental organization, it turns out, there are ways around bureaucratic hurdles.

Lagomasino and Fatoyinbo thought Goldberg could help them use satellite data to map mangroves - muddy, tangled-trunk forests that fringe the coastlines of dozens of tropical countries and as far north as St. Augustine, Florida. Mangroves are critical ecosystems: They store huge amounts of carbon and nurture fish and shrimp species that millions of people depend on for food. But much about them remains mysterious.

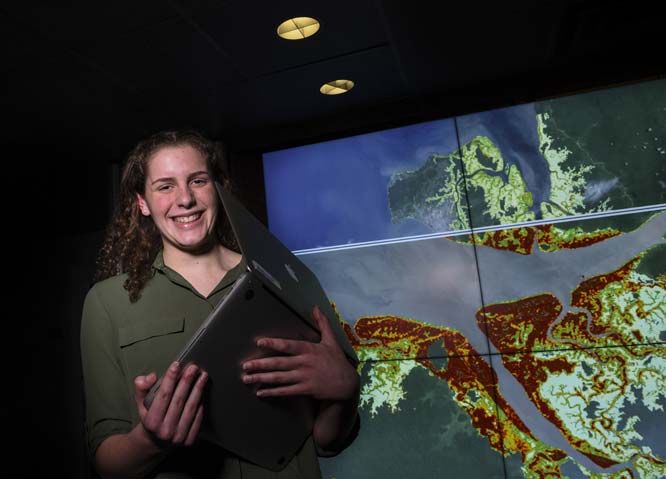

Less than two years later, Goldberg has developed what might be the world's first satellite-based early warning system to determine where mangroves are threatened. The work incorporates data from four satellites on mangrove growth and loss, rainfall, agriculture, and urban growth. Green, yellow and red pixels on a Google Earth base map indicate threat levels ranging from low to high.

Going from knowing almost nothing about satellite imagery to doing serious science at a world-renowned research facility has been a whirlwind for the sophomore at Atholton High School in Columbia, Maryland. "I still sort of can't believe I'm there," she said.

Goldberg grew up in the suburbs between Washington and Baltimore. She recalls elementary school field trips to the Chesapeake Bay and labs on water quality testing and rearing horseshoe crabs as part of a gifted and talented program.

Lagomasino and Fatoyinbo brought Goldberg on during the summer before she started high school. "I remember just really being in awe of the work they were doing," she said. Goldberg had seen mangroves only once before, during a trip to Fort Myers, Florida. Soon, she would see many more, at least on her computer screen.

She spent much of that summer analyzing images taken by NASA's Landsat satellites of the African coastline and determining whether she was looking at mangroves, water or bare mud flats. She did 10,000 classifications in one week, she said. Her advisers soon realized she was ready for something a bit more creative.

About that time, reports came in that nearly 30 square miles of mangrove forest had disappeared from a bay in Australia - one of the largest mangrove diebacks ever seen.

"It was really crazy to be seeing mangroves in the news," Goldberg said. She also learned that half of the world's mangroves had disappeared, and that much of what remained was threatened by sea level rise and erosion and by farming, urban development and other human activities. She was shocked - and galvanized to do something. "I didn't want to just analyze past loss," she said. "I wanted to create some kind of solution."

During the school year, Goldberg shifted to coming in once a week, on Friday afternoons. She read scientific papers on how to extract information on land cover from satellite data and learned to program in the JavaScript and Python languages. (She had studied coding and even taught it at a camp for elementary school girls, but her NASA work required her to take it to another level.) She took advantage of school breaks to put in extra hours at the lab. "I'll know it's spring break because Liza's here on a Tuesday morning," Fatoyinbo said.

She also worked weekends and evenings, logging in from home to the Google servers that host her computer code. Pretty soon, she was writing her own code with only occasional help from Lagomasino. "I was really taken aback that she was working on a project of this scope," said Hana Rhee, an Atholton teacher whose computer science class Goldberg took as a freshman.

With the early warning system, Goldberg's hard work is starting to pay off. Although a similar satellite-based warning system exists for tropical forests, the algorithm can't distinguish mangroves from nearby water, Lagomasino said, creating a need for a separate system for mangroves.

By July, Goldberg had made enough progress that Lagomasino persuaded her to submit a proposal to speak at the American Geophysical Union's fall meeting in New Orleans. The annual conference - one of the world's largest science meetings - brings together more than 20,000 Earth and space scientists. Only roughly a third of attendees get to give talks. When she received word that she would be speaking, Goldberg said, "I screamed so loudly I probably woke up the entire neighborhood."

She concedes that she was nervous when she stood up to present to a room full of scientists. "She impressed a whole lot of people," said Lawrence Friedl, the director of NASA's applied sciences program. "We joked up on stage - we were wondering whether she was in a master's or a PhD program at her school."

How often do high school students speak at the scientific meeting? "I don't think I've seen it," Lagomasino said.

Already, global conservation organizations are eager to use Goldberg's map to make their work more effective. It's more advanced than what her organization can produce, said Aurelie Shapiro, a mangrove researcher at the World Wildlife Fund's Berlin office. "There's an overload of data, and we just don't know how to use it all," she said. "Things like this NASA methodology can really help us whittle down what's important, what's happening and act on it."

Jorge Ramos of Conservation International in Arlington said the system could help his organization and the communities it works with determine where to allocate resources for maximum benefit. "It would be interesting to see what areas we work in show up as really high risk," he said.

Goldberg's next steps include incorporating additional data sources and making the warnings update in near real-time as satellite data stream in. She eventually plans to move the system to a public platform so a wider range of collaborators can access it.

Now that she has just turned 16, she has finally joined NASA'S official internship program. In a few months when she gets her driver's license, she may start driving herself. In the future she hopes to travel to East Africa to work with some of Lagomasino and Fatoyinbo's collaborators.

Longer-term, Goldberg envisions a career in science. "My mom always taught me that it's really important that you love your job, because that's what you do every day," she said. "And I love what I do at NASA." She's already thinking about colleges, with an eye toward ones that will allow her to do research her first year.

But first, she needed to make up year-end exams she missed while in New Orleans - and go on another family vacation to Florida over the winter holiday. Seeing mangroves was a priority. As her father noted, Goldberg knows of a map that shows where to find them.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author