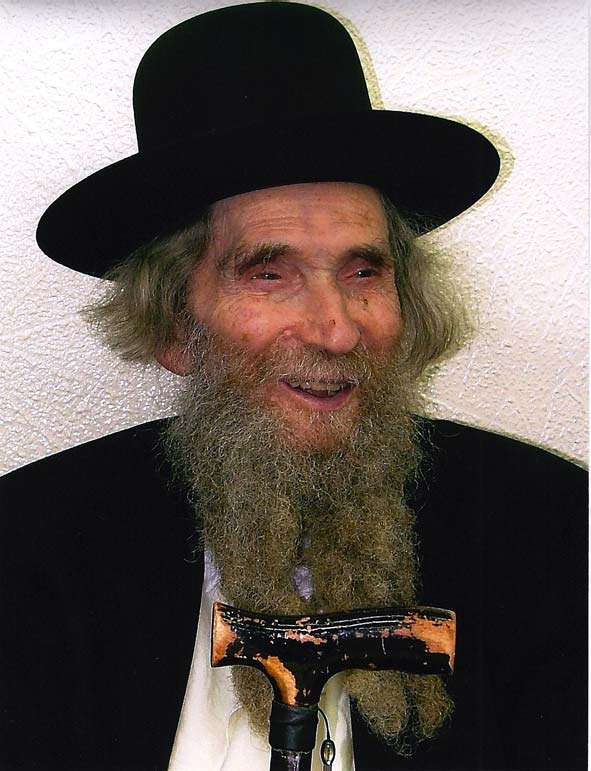

A 104-year old sage's last request and a lasting link

The unvarnished humility apparent in Rabbi Aharon Leib Steinman’s last request touched the hearts of those far away from Torah, making even the most estranged Jews think that maybe they, too, can become a link in the chain.

It’s been four weeks now, yet the sense of mourning for the loss of Rabbi Steinman, who lived until 104, hasn’t lifted. Every day new stories emerge, testifying to the greatness of this man who left us bereft.

I’d like to share with you a testimony to the profound effect of Rabbi Aharon Leib’s will, read aloud at the funeral and subsequently publicized in the media all over the world, on Jews all over.

The will asked that no eulogies be given, that no obituaries be written, and advised that followers not even name their children after him (because he wasn’t really what they thought he was).

The following was e-mailed to me by a fellow Jew who received it from the speaker himself, a university student entrenched in liberal thinking. Here is the text:

“As one brought up in the Hashomer Hatzair secular Zionist system, I never felt that Jewish identity had any meaning for me. I am much more Israeli than Jewish. I’ve never felt that I had any special part in the chain of Jewish tradition passed from generation to generation. As far as I’m concerned, the relevant part of my people’s history begins with Zionism and the rebirth of Israeli nationhood.

“This morning, when I heard Rabbi Steinman’s will read over the radio, I suddenly felt something I’d never felt before. I was proud to belong to the same people that Rabbi Steinman belonged to.

“Suddenly, a strong feeling of pride welled up in me, pride in being a Jew, of being part of something great and important. I felt very proud that I, too, am a link in the Jewish chain that brought forth individuals like that. And all day I’ve been wondering if perhaps I, too, even have a role to play as a link in this magnificent chain.”

I was intrigued. I wanted to know more, to understand what exactly was the power of Rabbi Steinman’s simple words to trigger such a reaction in such a devotedly secular student — and not only in that student, but in people all over the world. According to Israeli foreign correspondents, many prominent non-Jewish papers showcased Rabbi Aharon Leib’s will. And what was it, in fact, about that will that moved simple Jews like myself to tears?

I brought the question to a scholar, who explained it as follows:

“When people are exposed to something like Rabbi Steinman’s will, they are confronted with a unique personality that towers above anything familiar to us. It brings us face-to-face with lofty concepts that seemingly have no connection to our everyday lives. Yet the soul, the Divine spark within each one of us, feels a tremendous yearning for that level of moral purity and holiness that seems so elusive and unattainable. This longing makes us agitated, as if our soul is pleading to break out of its material confines, to rise above the raging urges of the heart, the enslavement to money, the pursuit of honor, and all the other evils that envelop us on all sides. If we feel agitated, it means that we, too, would like to be there, in that luminous world where Maran spent his life. He said about himself that he never had a sad day, despite all the suffering that afflicted him. Yet the present seems to be stronger than our dreams, and pulls us back down again, until the longing gradually fades.”

Many years ago, Rabbi Shmuel Chassida and I collaborated on a page called “Know Your Judaism” for the secular newspaper Maariv, and every now and then we were astounded by the responses of very secular Jews. One day we were on the printing floor when the well-known secular author Moshe Shamir came up to us. “That profile you wrote about the Chofetz Chaim,” he asked, “is all that really true, all that about how careful he was not to steal a penny and not to say a word that could harm anyone?”

It was simply hard for him to believe that such a person could really exist. Once we managed to convince him that all we’d written was well documented, he looked stunned — and saddened. After a long, ponderous silence, he said, “Kol hakavod!”

I once devoted the entire Maariv space to Rabbi Yisrael Salanter, going into detail about the incredible heights he reached in his conduct bettween man and his fellow. A week later, letters came in from directors of cultural affairs at left-wing kibbutzim, inviting us to come and give a talk about this amazing personality. In every venue where I had the opportunity to speak about the lives of Jewish religious greats and the refinement of their characters, I always heard the same response: “Even though I’m not a religious Jew and I don’t keep all the religious duties, right now I’m proud to be a member of Jewry if it produces people like that.”

Like the luminaries who preceded him, Rabbi Aharon Leib Steinman had the merit of making a great kiddush Hashem even in his death. He merited being a vehicle for the Divine presence — his constant, lifelong aspiration was to bring the Lord to even the most distant Jews. Who can possibly gauge the depth of the effect wrought upon that student who suddenly felt proud of being a Jew? What distance did that young man, in one moment, from a world of shallow values, prejudiced beliefs about Torah Jews and about the very concept of being a Jew, to a sense of actually being a link in the chain, and perhaps having a role to play in the Divine’s world?

And in the knowledge that it was of utmost importance to Rabbi Steinman to expand the place of love of one's fellow in our lives, permit me to share three anecdotes that exemplify the height of his resoluteness in this area of the Torah.

A lawyer who had become somewhat secularized in his lifestyle came to Rabbi Steinman complaining that several Jewish schools, fearing his potential negative influence, had refused to accept his son. Rabbi Aharon Leib tested the youth and concluded that he was certainly fit to be a mainstream yeshivah student. He intervened on the family’s behalf, and the boy was accepted. When he gave the good news to the grateful father, Rabbi Aharon Leib told him, “I expect something in return for my efforts on your son’s behalf.”

The father, being well off financially, assumed that the sage was expecting a handsome monetary donation to his charity funds.

But Rabbi Aharon Leib went on to say, “The compensation I want from you is this: Erase from your heart all anger, resentment, and criticism of the educators who initially refused to accept your son.”

On another occasion it happened that an eight-day-old boy became dangerously ill right before his scheduled bris (circumscision). The doctors who made the diagnosis said the baby needed a lifesaving procedure that could only be done abroad, but there was some doubt as to whether he would survive the journey. Rabbi Steinman ruled that they should take the risk and go for the procedure. Three months later, the baby returned home healthy and ready for his bris. The happy parents wanted the sage to accept the honor of being godfather.

Rabbi Steinman wouldn’t hear of it. “You came to me about the child’s illness on the day he was originally supposed to have his bris. That means you already chose a godfather then. How can I take that honor away from him?”

One last story: A community-conscious person came to consult with him about starting a non-profit for loaning of wedding gowns. Rabbi Steinman agreed that this would be a worthwhile endeavor for the family, but he laid down one condition: Each gown should be used by no more than three kallahs. The man was perplexed by this condition, and so Rabbi Aharon Leib explained, “These gowns are made of delicate fabrics. After they’ve been worn and cleaned three times, the fabric becomes limp or even damaged, and a bride won’t feel at her best in such a gown.”

In other words, don’t let your kindness become something that could cause discomfort to the individual whom you want to help.

Rabbi Moshe Grylak is editor-in-chief of Mishpacha magazine, an international glossy, from where this article is reprinted. He is the author of several books on Judaic themes.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author