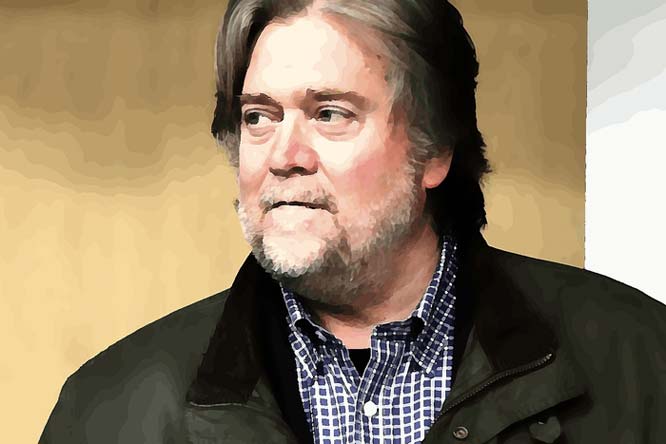

Steve Bannon's claim of executive privilege in his refusal to answer questions this week from the House Intelligence Committee is raising a novel and somewhat difficult problem: Should there be executive privilege for communications between the president and his close advisers during the transition period between the election and the inauguration?

On the one hand, the president's need for candid advice starts before he takes office. On the other hand, there's something strange about applying a constitutionally based executive privilege to someone who is not, after all, the executive.

The only way to resolve the question is to delve into an issue that courts have tried to avoid, namely the underlying logic of having executive privilege at all.

The basic idea goes all the way back to George Washington, who strongly resisted House efforts to get hold of his correspondence with John Jay, the special representative who negotiated the controversial treaty that re-established relations between the U.S. and Britain after the Revolutionary War.

Washington's rationale was primarily functional. "The nature of foreign negotiations requires caution," he wrote to Congress in refusing the demand, "and their success must often depend on secrecy."

But Washington also hinted at a constitutional basis for his refusal by saying that he had no intent to "withhold any information which the Constitution has enjoined upon the president as a duty to give." The implication was that the president had the right to keep his own diplomatic correspondence away from Congress.

A similar tension was manifest in the Watergate tapes case, U.S. v. Nixon, in which the U.S. Supreme Court finally recognized the executive privilege for the first time. The justices unanimously said that executive privilege was rooted in "the supremacy of each branch within its own assigned area of constitutional duties" and in the separation of powers.

Yet the court also held that, "absent a need to protect military, diplomatic, or sensitive national security secrets," executive privilege would not prevent disclosure of material necessary for criminal charges. This was pragmatic balancing, not abstract constitutional principle -- and President Richard Nixon had to hand over the tapes.

When it comes to the period of the presidential transition, the issue of executive privilege may well depend on which matters more, pure separation of powers or practical interest.

If you think that executive privilege exists because the president can't be pushed around by Congress and the courts, then the Trump administration and Bannon shouldn't be able to take any refuge in executive privilege for anything that took place during the transition. During that time, Barack Obama was president. The foreign affairs power belonged to him, not Trump.

This perspective is reflected in many Democrats' view that there was something wrong with Trump and his national security adviser-designate, Mike Flynn, trying to do foreign policy during the transition. There's only one president at a time, goes the thinking -- so there should be only one foreign policy actor speaking on behalf of the executive.

Yet there is a nontrivial argument to be made that the transition is a crucial moment for coming foreign policy goals. Not only must the president choose his seniormost national security official, but he and they must go through a series of extremely detailed briefings on how U.S. foreign policy and military policy is being conducted. Then the president and his advisers presumably discuss those briefings in private.

Those briefings and discussions are just as instrumental to the shaping of foreign policy as anything that takes place after the president swears the oath of office. To the extent executive privilege is appropriate to protect a conversation that might take place after inauguration, it seems very sensible to apply the same logic to an identical conversation that takes place before the inauguration.

There's no simple answer here. But a solution might be found in extending the privilege to the transition, while simultaneously drawing the privilege very narrowly, even after the president takes office.

Consider the context of foreign affairs. True, the presidential power to make foreign policy is closer to exclusive than almost any other. And the questions from Congress that Bannon doesn't want to answer may well have to do with making foreign policy.

Yet the courts have also said that even on foreign policy, presidential power doesn't translate into absolute privilege. In a 1977 case, U.S. v. AT&T, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit pointed out that Congress still has national-security-related powers, including the power to declare war and, in the case of the Senate, approve treaties. The court then refused to resolve a dispute about the privilege between Congress and the president until the two sides tried to negotiate a solution.

The upshot is that Congress has a role to supervise and participate in foreign policy -- and so executive privilege shouldn't extend so far as to protect all conversations between the president and his advisers that might happen to touch on foreign policy.

That's especially true when the conversations might trench on criminal conduct. The lesson of the Watergate tapes case is surely that the executive branch may not hide behind privilege to cover up knowledge of crimes.

This proposed compromise may satisfy no one from a partisan perspective. But extending executive privilege to the transition while defining the privilege narrowly may well be what's best for the country -- and national security.

Comment by clicking here.

Noah Feldman, a Bloomberg View columnist, is a professor of constitutional and international law at Harvard University and the author of six books, most recently "Cool War: The Future of Global Competition."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author