From Buenos Aires to Hiroshima, President Barack Obama has spoken of the harm done abroad as a result of his predecessors' foreign policy decisions.

The most recent instance occurred during his visit last week to tiny Laos, where he reviewed the destruction wrought by U.S. bombing of that country during the wars in Southeast Asia nearly half a century ago. "Countless civilians were killed," he lamented.

Republican critics in this country have derided these "apology tours," but that's not fair. Obama has generally stuck to passive-voice formulations, as he did in Laos, and avoided explicit apology.

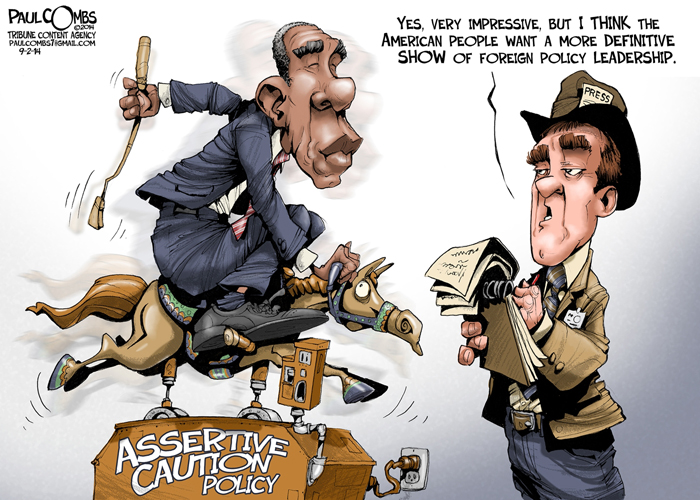

Still, the moralizing comes through, which raises a question: Just how different is Obama's conduct from that of the past presidents whose judgments he reviews today?

Obama said the U.S. air campaign in Laos - aimed at North Vietnamese communists who were illegally using the neutral country as a supply route to South Vietnam - not only caused massive collateral damage, it was also "a secret war," whose full scope is not widely known "even now."

Adjusted for the greater precision of modern weaponry, you could say something similar about the nontransparent U.S. campaign of drone strikes against suspected terrorists that Obama is conducting around the Middle East today, at the cost - minimized but unavoidable, the administration says - of many innocent civilian lives.

In March in Argentina, Obama noted the anniversary of a 1973 military coup, calling the Nixon and Ford administrations' initial acceptance of the junta a case of betrayed American ideals, in which the United States was "slow to speak out for human rights." He offered disclosures of U.S. classified documents about the period as a form of penance.

One wonders what archives will eventually reveal about Obama's own tolerance of the brutal military regime in contemporary Egypt, which took power in a 2013 coup, and which the United States, after a brief suspension, supplied with more than a billion dollars in military aid - made possible by an administration waiver of human rights conditions in U.S. law.

The New York Times' analysis of Obama's Laos speech appeared on Page A8 of its Sept. 8 edition. On Page A9, a headline read: "Pressing His Asia Agenda, Obama Treads Lightly on Human Rights." The accompanying article explained how, in dealing with the dictators of China, Vietnam and, indeed, Laos, Obama played down their repressive rule for the sake of other diplomatic goals.

Page A10 carried the claim by Turkey's authoritarian president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, that Turkey and the United States were readying joint military action against the Islamic State in Syria. That might or might not pan out - Erdogan has blown smoke about such matters before. But Erdogan had just met with Obama, after which the latter praised Turkish "cooperation" against the Islamic State, said the two leaders had "discussed ways in which we can further cooperate in that regard" - and glossed over Erdogan's nationwide crackdown on political opponents in the wake of a failed July coup against him.

Obama must believe that U.S. national security requires him to make these trade-offs, or that his course will minimize civilian deaths, and maximize human rights, over the long run. Or all of the above.

In other words, he must be telling himself exactly what his predecessors during the Cold War (and Harry Truman at Hiroshima) told themselves.

Susan Rice, the president's national security adviser, framed the president's retrospective comments as an effort "to face and acknowledge our history," by noting "points of departure" from the United States' "overwhelmingly positive" global role.

Perhaps, but the clear implication of Obama's expressions is that the U.S. effort to stop the Soviets from accumulating global power and influence was often unjustified in view of the costs.

When discussing the bombing of Laos, for example, the president was evaluating part of a wider struggle, Vietnam, that he had already publicly labeled a "quagmire" that "ultimately . . . weaken[ed] us."

Fair enough. Still, at the time of Vietnam - and the Argentine coup, and the revolution in Cuba - U.S. presidents considered the nuclear-armed Soviet Union, not implausibly, as a mortal threat to us and our allies. We'll never know what, say, Latin America would be like today if the United States had done nothing to stop Cuban attempts to spread revolution during the Cold War, though the current chaos in Venezuela suggests a possible outcome.

Today, Obama seeks to work with the likes of Erdogan against the Islamic State even though he believes the terrorists "do not threaten our national existence," as he put it in his January State of the Union address.

Erdogan certainly seems like the lesser of two evils - but Obama's policy is nevertheless one of many moral compromises during his tenure, including his fateful decision not to intervene militarily in Syria.

Someday Obama, too, will face history's judgment. Meanwhile, he ruminates on the doleful impact of his predecessors' choices, seeking to communicate a certain humility about his country.

Less intentionally, he communicates a certain lack of humility about himself.

.

Comment by clicking here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author