On the night of the New Hampshire primary in 1992, Bill Clinton began his speech by declaring that "New Hampshire has made Bill Clinton the comeback kid," but by its end he was announcing a kind of tactical shift. The message of empathy for middle-class pain that had dominated his campaign-and carried him to second place in the economically depressed state-was far from the animating cause of his bid to lead the Democratic party. "Tomorrow morning I will carry this campaign away from New Hampshire," Clinton said. "I will go all across this county, to the rest of the nation, asking them to embrace the New Covenant that I have advocated to restore opportunity and increase responsibility and rebuild a sense of the American community."

To anyone who had followed the opening phase of Clinton's life as a national figure, "New Covenant" was familiar code for the bundle of policy positions-many cultivated by the moderate Democratic Leadership Council-that allowed the Arkansas governor to introduce himself to the country as a New Democrat. Each represented a carefully calibrated diversion from the liberal orthodoxy of the previous decade; Clinton expressed little patience for identity politics, was a cheerleader for free trade and held to an unrepentantly hard line on crime and drug use. Just three weeks before the New Hampshire primary, Clinton refused a request for clemency against Ricky Ray Rector, a mentally disabled double-murderer, whose execution offered a useful occasion to demonstrate his unambivalent view towards the death penalty.

Only one other person stood on the stage that primary night at the Best Western Inn in Merrimack, and while Clinton did not name his wife, Hillary, in the speech, he told his auditors that without her "love and friendship over twenty years I wouldn't be here tonight and wouldn't be fit to be here tonight."

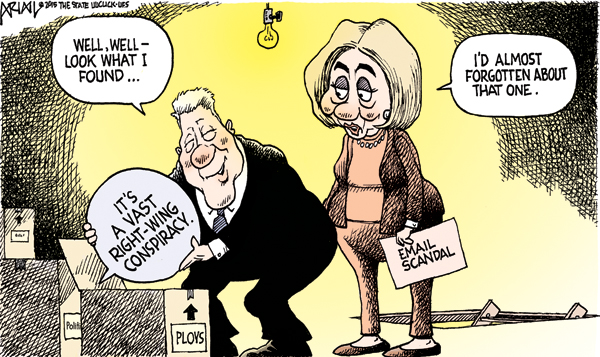

On Tuesday night in Manchester the roles were reversed, with Hillary behind the podium and Bill flanking her, and in a way her candidacy is built on his 1992 run. But in other ways, his legacy is one she's had to live down.

In her concession speech after her devastating loss to Bernie Sanders, Hillary called herself the "best change-maker" but the vision of change she had articulated during her New Hampshire campaign diverged pointedly from her husband's. In a single debate last week, Hillary Clinton affirmed her opposition to every major multilateral trade pact of the last the last quarter-century, volunteered concern for the politics of racial and sexual identity and implied she might be pleased to see the U.S. Supreme Court again ban capital punishments by states.

Perhaps notably she has taken umbrage at being called a moderate, even though until recently she happily wore the label as a badge of honor. If she did not share his surname, the entirety of Hillary's candidacy could be reasonably understood as a challenge to Bill's political legacy.

For Hillary to survive, Clintonism had to die.

That is the defining formulation of her 2016 campaign-and it stands to challenge her throughout both the primaries and a general election. As she trekked from campaign stop to campaign stop in New Hampshire this past week, Hillary Clinton worked to juggle nostalgia for past Clinton primary campaigns in the state with the fact that the Bill of 1992 or the Hillary of 2008 would likely be a marginal figure within today's Democratic politics.

"Could a young Bill Clinton with his talents and his ability to think through complex issues and express his conclusions intelligently enough, could that Bill Clinton be nominated by the Democratic Party? You betcha," said William Galston, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who helped write Clinton's speech laying out his "New Covenant" agenda. "Could he take the DLC platform of 1991 and sell it now? The answer is no."

Upon ascending to the DLC's chairmanship, in 1990, Clinton told the group that "any political resurgence for the Democrats depends on the intellectual resurgence of our party." At that same conference, in New Orleans, DLC leaders signed onto a policy statement which laid out goals "to expand trade, not restrict it" and "preventing crime and punishing criminals." In its entirety, though, the New Orleans Declaration could best be read as a rejection of the forces that had elevated Jesse Jackson's "Rainbow Coalition" candidacy for president two years earlier. "We believe in the protection of civil rights and the broad movement of minorities into America's economic and cultural mainstream, not racial, gender, or ethnic separatism," it asserted.

The overarching project was to win back working-class white voters who had chosen Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush over Democratic challengers. In an influential 1989 article, "The Politics of Evasion: Democrats and the Presidency," Galston and Elaine Kamarck criticized party leaders for having "manufactured excuses for their presidential disasters," seeking solace in their congressional majorities and expecting new personalities and improved mechanics to help them retake the White House. Instead, Galston and Kamarck wrote, the next nominee "must recast the basic commitments of the Democratic Party in themes and programs that can bring support from a sustainable majority."

Bill Clinton was the embodiment of this approach, willing to antagonize the party's core constituencies with centrist positions and a language of moral disapproval. Unlike Walter Mondale and Michael Dukakis, Clinton denied Republican opponents any opportunity to portray him as soft on crime, weak on foreign policy, coddling of welfare recipients, or unwilling to confront the injustice that racial quotas presented to those who were denied work or education because of them."When Bill Clinton was labeled a moderate, it helped him, even in the primaries," DLC founder Al From wrote in a 2013 book The New Democrats and the Return to Power.

Hillary has not discarded Bill's belief that a good strategy for winning the nomination is one that will not require backtracking in the general election. Even as she's swung left, there are touches of caution in her strategy, and her emphasis on national security is arguably more useful next November than in February. But while she reiterated her husband's cautious formulation that he wanted to see abortion "safe, legal and rare"-"and by rare I mean rare," she emphasized in 2008-in the face of Republican challenges to public funding for Planned Parenthood, she has become a far less reluctant champion of access to abortion.

Where the New Orleans Declaration that her husband embraced put the onus on minorities to embrace the "economic and cultural mainstream, not racial, gender, or ethnic separatism," Clinton twice in last week's debate expressed concern about the "continuing challenges of racism, of sexism, of discrimination against the LGBT community." There were hints this was not her natural posture-she secluded the observation in her opening and closing statements, but never managed to direct the conversation there in between.

Throughout this campaign, she has struggled with her own situational identity. Even as she attempts to reap the rewards of Clintonism-citing her husband's record on job growth to support the contention that "the economy does better when you have a Democrat in the White House"-Hillary has eschewed many of its signifiers. When self-described Socialist Bernie Sanders reminded voters that just months earlier Clinton had proudly called herself a "moderate," her team recoiled as if the term was a slur. "If you look at the totality of what she said that day, she was defending her past work with Republicans in favor of getting things done," Clinton spokesman Brian Fallon said last week at a breakfast sponsored by Bloomberg Politics.

The Democratic campaign trail remains littered with the detritus of Clinton's presidency. His enactment of the 1994 crime bill and the Defense of Marriage Act two years later, along with pro-business views towards globalization and deregulation, have afforded Sanders to claim that even as Clinton now claims to be a "progressive" her record does little to illustrate accomplishment in that area.

Events have clarified some of the hard choices a Democratic candidate in her position would once had have had to make. The 1996 bill to reform welfare programs and long-term decreases in violent crime removed two intimidating constellations of issues from the political galaxy. Supreme Court decisions about the same-sex marriage and affirmative action had constrained political debate around those policies. This year, Clinton has said she would "breathe a sigh of relief" if the Court did the same by reimposing a national ban on the death penalty.

On economic issues, Clinton has not been as passive, largely because voter anxieties today focus less on stagnation than inequality. During the Clinton expansion of 1993 to 2000, incomes went up 20.3 percent for the bottom 99 percent of Americans. Meanwhile, Americans real incomes dropped 11.6 percent among the bottom 99 percent during the great recession of 2007-2009 and from 2009 to 2014, under President Barack Obama, income for all but the top 1 percent grew by only 4.3 percent, according to research by Berkeley University economist Emmanuel Saez. "Voters are definitely perceiving a much broader series of villains in the economy than there was then," says Kamarck.

Hillary Clinton has begun to advocate for stronger rules to constrain the financial sector, even attacking Sanders for his 2000 vote in favor of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, which President Clinton signed into law. At the same time, she has doubled down on her criticism of his North American Free Trade Agreement and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, even though she has spoken favorably of both in the past. "I do think that a lot of people who have have supported trade agreements in the 1990s would have a different point of view today," said Pennsylvania Sen. Bob Casey, a long-time skeptic of trade pacts who opposed Clinton during the 2008 primaries but is campaigning for her this year.

"Some people think the reason Republicans went so far right is the Democrats took up the middle and left them no room so they had to go far right," says Kamarck, now a senior fellow at Brookings and author of the book Primary Politics, reissued last year. "The Republican right has really gone off the rails in the last decade. The Republican party is no longer a center-right party; it's a far-right party. They're pushing some things that require Democrats to hit back hard."

What Galston and Kamarck had dismissed as "the myth of mobilization"-the idea that Democrats should stop obsessing over centrist swing voters and focus instead focus on turning out non-participants who already shared their values-is now treated as undisputed reality among many leading Democrats, including those guiding Clinton's campaign. They believe her path to the presidency will be built on what pollster and former Clinton adviser Stan Greenberg describes as "the Rising American Electorate." As he wrote last week with Voter Participation Center founder Page Gardner, that left-leaning coalition of unmarried women, people of colors, and millennials who, "makes up the majority of eligible voters and this year, for the first time in history, could comprise the majority of votes cast in a national election."

Hillary didn't leave the center as much as she saw the center leave American politics. "There has been a hollowing out of the center, whether you're talking about the center-right or the center-left," says Galston. "You're witnessing it up close in New Hampshire. The center of gravity in the parties has shifted." As a result, many Democratic strategists feel it is now effectively impossible to go too far left and remain viable in a general election-and some even feel that dramatic leftward lurches are imperative to keep peripheral Democratic voters engaged.

Conservative Democrats who just a few years ago agitated for caution around fractious cultural issues are now resigned to the fact that there is little electoral case they can make about the risk of alienating swing voters. "America is more polarized than it was then-you have a harder right and a harder left," says Arkansas Sen. Mark Pryor, whose predecessor and father David was Bill Clinton's most prominent out-of-state campaign surrogate during the 1992 New Hampshire primary.

In 2008, Hillary Clinton opposed gay-marriage rights, wavered on whether she thought illegal immigrants should be issued drivers licenses, and cast herself as such a fan of guns that Barack Obama mocked her for "talking like she's Annie Oakley." This year, her enthusiasms have swung her in an opposite direction. Even before she had to take seriously Sanders's challenge, Clinton had committed herself to full legal equality for transgendered people, mused that an Australian- style gun-confiscation program is "worth looking at," and said she thinks immigrants should be eligible to buy medical coverage on exchanges created by the Affordable Care Act regardless of their legal status. "A lot of wedge issues in '92 just aren't there anymore," says Kamarck. "It's been amazing to me how much the cultural issues have fallen off the table. The new generation coming into the electorate just doesn't care about those issues."

Today it is Republicans who debate their party's "manufactured excuses" for two consecutive losses to Obama, although some who lived through the Clinton era are also alert to the possibility that Hillary's 2016 platform might represent a dangerous overcorrection by Democrats. "Bill Clinton recognized there was a great middle in America that he had to have some appeal to," said former congressman Bob Walker, who served as the Republicans' chief deputy whip during the 1992 and 1996 elections. "To some extent it's inevitable, in that she's trying to appeal to a primary voter and she doesn't want to be caught in the way she was caught in 2008. She has to have some way of getting through the primaries, and that's a very tough road right now. But it does make it easier for us to define her in the fall."

When challenged in 2004 by NPR host Terry Gross about views that she implied had shifted to keep up with "the American public" on gay marriage, Clinton portrayed the combination of political nimbleness and policy entrepreneurship as part of a national creed."I think I'm an American," Clinton said with a laugh. "And I think we have all evolved." As the two sparred often uncomfortably about whether that was a mark of opportunism and insincerity, Clinton articulated a theory of political evolution that could be understood as one of the natural laws of Clintonian physics. "You're not 100 percent set-thank goodness-you're constantly reevaluating where you stand." She changed, she finally conceded, because the country had changed.

Previously:

• 11/25/15: A new data-mining technique to uncover New Hampshire 'influencers'

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author