Yes, the House Republican conference is stunned and confused after the withdrawal of Rep. Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., from the speaker's race. But is it any more stunned and confused than it was exactly two years ago, when the government was partially shut down amid bitter House GOP infighting over Obamacare? Or a year ago, when House Majority Leader Eric Cantor suffered a mind-blowing defeat in a GOP primary election?

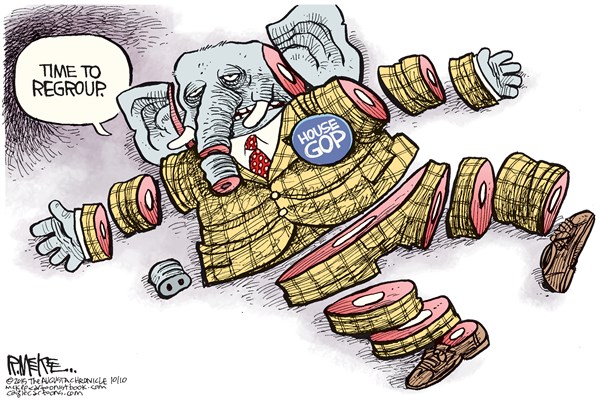

The fact is, the chaos plaguing Republicans in the House has been building for a long time. It's no wonder some GOP lawmakers were reportedly weeping in the Capitol after McCarthy's announcement.

Not long after, McCarthy was asked by National Review Online whether House Republicans are, at the moment, ungovernable. "I don't know," he said. "Sometimes you have to hit rock bottom."

The GOP's problem is that there is no way to know whether this is rock bottom or not. Things could get worse. There's certainly no reason to believe they will get better anytime soon.

The fundamental cause of the disarray is lawmakers' inability to answer to this question: What is the role of a Republican Congress in opposing President Obama? Republicans took over the House in 2011, and they haven't agreed on that yet.

After the GOP's smashing victory in Obama's first midterm, in 2010, Republicans came to Washington and immediately began squabbling among themselves. Why had they won the majority? Was it because they promised to repeal Obamacare? Was it because they promised to reduce the size and scope of the federal government? Was it because, as the new Speaker John Boehner believed, they promised to create jobs?

The argument became so intense that Republicans actually commissioned a private poll, which found that by a large majority, Americans voted for Republicans to create jobs. Obama didn't seem terribly interested in jobs during his first couple of years in office, and frustrated voters wanted Congress to take action.

"There has been a misunderstanding over how we got our majority," says a well-connected GOP strategist who works closely with Hill Republicans. "In 2010, what was the number-one issue? It was not health care. It was jobs and the economy by a more than 60 percent margin."

Nevertheless, a lot of newly elected GOP members were driven by opposition to Obama. They had never served in the majority before and did not come to Washington to get along and go along. They pushed Boehner to be more and more confrontational. They realized that with Democrats in lockstep defense of the White House, even a relatively small group of Republican members -- 30 or 40 -- could stop Boehner from passing spending bills or other critical legislation.

The partial shutdown was the result. Boehner's days were numbered after that.

But Boehner's retirement announcement -- like McCarthy, he sprung it on a surprised world -- didn't resolve any of the conflicts inside the GOP conference. Many of that core 30-40 member group of the most assertive conservatives saw McCarthy as more of the same. And they realized, again, that if they voted as a bloc against leadership, McCarthy couldn't become speaker.

And why should he have asked the conservative rebels, who like everyone else watched as public approval of GOP leaders went down and down?

"When 72 percent of Republican voters disapprove of the congressional leadership, it's hard to simply promote the next in line," says one conservative member. "We are in a representative business, and it is unsustainable to have the people who do so much work to send Republicans to Congress harbor such dissatisfaction with the party's leaders."

On the other hand, among the large majority of House Republicans who aren't part of the rebel group -- that would be about 200 members -- there are some who are deeply angry at the conservative firebrands.

"Didn't Jim DeMint say it very clearly?" asks the GOP strategist, referring to the very conservative former senator. "DeMint said he would rather have 30 true conservatives in the Senate than 60 that don't really have principles. Of course, with that, you won't have any say in how the government works. Now, what (the House firebrands) are saying is, forget if we don't have any say, forget if we can actually do anything, the key thing is to be able to say what we want."

That's the fight that caused the McCarthy melodrama. (Yes, his Benghazi comments were a disaster, but the basic conflict inside the House GOP conference was a much bigger factor.)

Yes, it is reasonable to ask whether Republican leaders -- the experienced ones steeped in the ways of Washington and, in particular, of K Street -- did everything they could to understand the priorities of the conservative militants.

But it's probably too late for understanding now. The speakership is up for grabs, the conference is in disarray, and rock bottom might not even be in sight.

Comment by clicking here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author