As a career academic who teaches entrepreneurship, I am very familiar with the anti-business sentiment that pervades so much of higher education and the public discourse about policy in this country. It is a spreading plague grounded in infuriating ignorance.

So when I run across articles like "A Time to be Bold," in Jacobin magazine, I want to pull my hair out.

The article, proclaiming the advantages of socialism over capitalism, features sweeping generalizations like these:

—"Capitalism is the chief source of human suffering today and a system that promotes the worst of human behaviors."

—"Because a small number of people own the productive assets of society, most people have to seek out these businesses for work."

—"Socialists believe that people should care about and care for each other. Capitalist markets, on the other hand, divide."

The authors insist that society's ills can be resolved with state ownership of all private property, redistribution of all wealth and collective decision-making about what to build, make, produce and sell.

What a prescription for disaster! (And how many times do we have to see these ideas fail?)

The article is constructed on one flawed assumption after another.

First, the authors seem to be equating business with huge multinational corporations. But most businesses in the U.S. are small. The U.S. has approximately 28 million firms. Of those, about 21 million — nearly 80 percent — employ no one but the owner(s). Of the remaining 7 million companies, the vast majority employs fewer than 20 people. Further, most businesses in the U.S. aren't incorporated, but of those that are, fully 80 percent are small, closely held corporations owned and operated by families.

Second, millions of people — not a small handful — own their own businesses and the property in them. Hundreds of thousands more start new businesses every year.

Third, most entrepreneurs fund their startups with savings — not daddy's trust fund.

Fourth, it takes a lot to grow an idea into a successful business of any size — much less a multinational corporation. A lot of what? Not money. Not power. Satisfied customers.

Far from being exploited victims, we as the consuming public weigh in on what we want from businesses every single day. Don't think so? I'll bet that wired-telephone manufacturers, camera filmmakers, newspapers, bookstores and record companies would love to have the business they had in the 1980s. But they don't.

Why? Because inventors and entrepreneurs have developed something new. And we — the public — decided we liked it better.

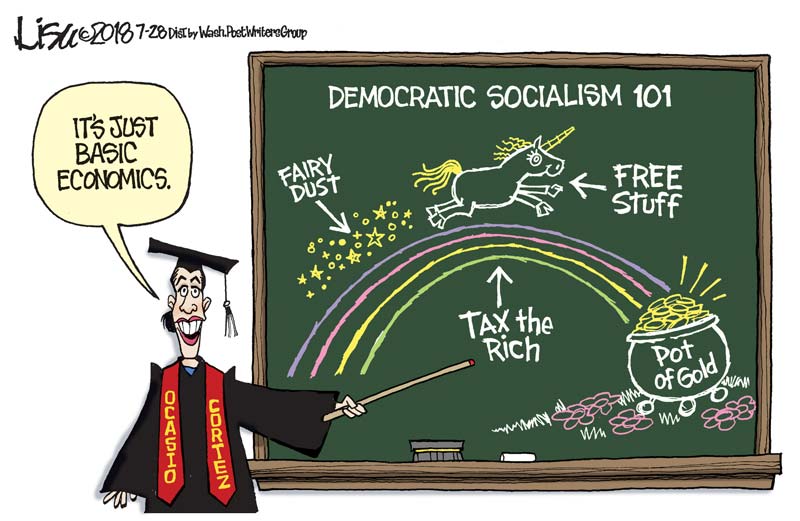

What you get with "democratic socialism" is a state bureaucracy or some "people's collective" deciding what products and services are available. Why should I have to settle for what the majority wants, if I want a niche product?

But this isn't just a question of a handful of disgruntled connoisseurs. Virtually all radically successful innovations (automobiles, the internet, smartphones) started as niche products, precisely because "most people" wanted what already existed. The companies that had become successful producing the status quo had no incentive to change. But some entrepreneur thought, " I want something different. Maybe others do, too."

Not only do entrepreneurs have to spend their own money to fund their ideas but they also then have to persuade you to part with your hard-earned cash for their product. If it's completely new, that task is even harder; why try Y when you've always used X? But if Y is good, people start to buy it. Small numbers, at first. Then more. And eventually, lots of people want this new thing.

That's how innovation works. That's how new businesses become big businesses.

Democratic socialism — like all collectivist systems — kills innovation, precisely because the objective is to produce what "the majority" already wants.

So, how do we get the things no one's ever heard of?

We don't.

Under the socialists' dream, you can kiss entrepreneurship and disruptive innovation goodbye. Top-down economic decision-making is structurally and systemically antithetical to innovation not only because it is majoritarian (at best) or authoritarian (at worst) but also because it is not user-centric. That's the kiss of death for both startups and established businesses. Once you think you know what your customers need better than they do, you're already dying, whether you know it or not.

The reason American businesses are so much more responsive to our needs than government is because businesses know (even if socialist writers don't) that the public does control business; make customers unhappy and in no time, they have gone to your competition, and you're out of money.

Of course, this assumes that the public has competitors to choose from.

Governments, by contrast, have no competition and no incentive to satisfy the public. They extract money from you by force (it's called taxation) and assume that the money will never run out. That isn't true, as citizens of Detroit, the state of Illinois or Venezuela can tell you with painful clarity.

The key is not to have businesses run like government (or, G od forbid, by government). The key is to make government as responsive as the best-run businesses.

(Note that I said "the best-run businesses," not ALL businesses or BIG businesses.)

This is the polar opposite of what the collectivists are clamoring for. But I'm right, and they're wrong. How can I be so sure?

Because entrepreneurship produces what the people want. And collectivism fails every time.

Comment by clicking here.

Laura Hirschfeld Hollis is on the faculty at the University of Notre Dame, where she teaches courses in business law and entrepreneurship. She has received numerous awards for her teaching, research, community service and contributions to entrepreneurship education.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author